Stuck at the end of many of our syllabi, wedged between university policies, college resources, and student honor codes, sits a section on land acknowledgments.

This paragraph, a word salad, lists Native American tribes that once lived on the land now used by the university, ending with the university acknowledging that it unfairly acquired the land.

But this serves as a way for the universities, such as Iowa, to bury deep their history while still claiming a moral solution to their past. It’s time we reevaluate land acknowledgments and consider if they do anything beyond their superficial existence.

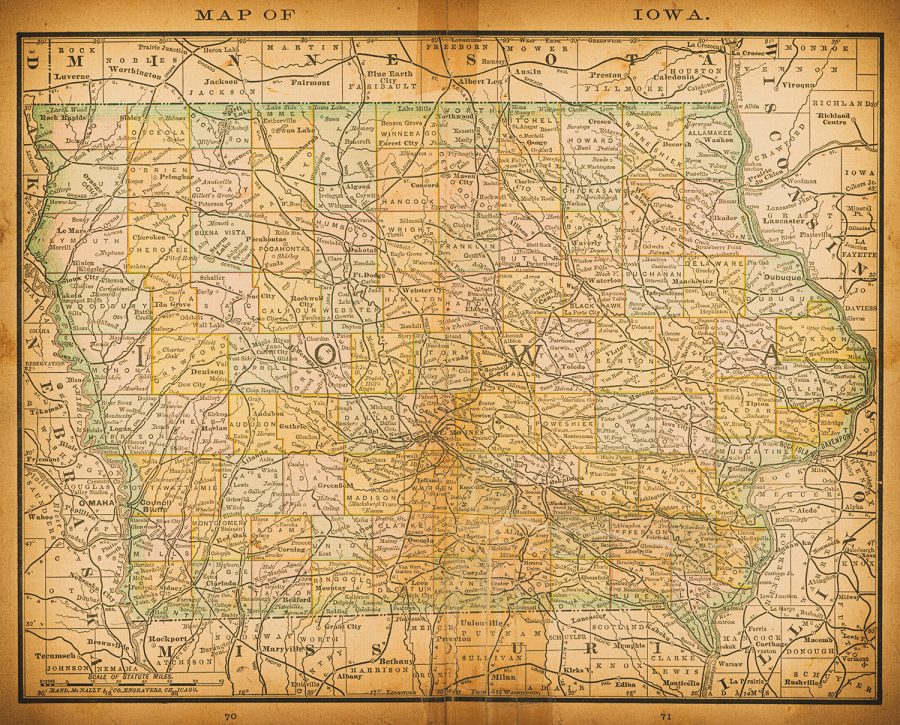

As mentioned, many syllabi include land acknowledgments. The university also has a page that goes into further detail. It covers the treaties that removed Native Americans from Iowa and lists the many tribes that have lived here before.

Both this page and the syllabus statements are buried and hard to find, never directly pointed to by the university. While on the surface, land acknowledgments are a good way of explaining the history of this land and the people who owned it; the university uses them as another form of housekeeping — a box to check on documents.

This approach is counterintuitive to the purpose of land acknowledgments, making them truly performative. Instead of being told about it, one must seek it out, leaving most people unaware of its existence, just as many are unaware of the tribes that once lived here.

Land acknowledgments should be presented at appropriate times, when the audience is engaged. Their purpose is to bring attention to both the past and the present, raising awareness about the current situation many Native Americans face and the reasons behind it.

Today, Iowa has a very limited Native American presence. The Meskwaki Nation, the only federally recognized tribe left in Iowa, owns over 8,000 acres in Tama County. This contrasts with the more than 19 tribes mentioned in Iowa’s land acknowledgment.

The university and its affiliates may want to help improve our history and relationships, but for now, we are stuck with a mere performance — visible only to those who go out of their way to seek it.

Land acknowledgments don’t help with what Native Americans really need — support. Native Americans are the most impoverished group, and many of our policies reinforce this. Our past and present systems are set up for them to fail.

Our current state is to feign support and acknowledge history, but only superficially. A university has significant power to improve the lives and situations of Native Americans —teaching students about the tribes that once owned the land and preparing young professionals in fields like law, policy, and even business to care about Native issues. But for now, we are stuck with a mere gesture instead of true action.