Mauricio Lasansky began his most impactful work in 1961 after inspiration was stirred by something he and thousands worldwide watched on TV sets. Adolf Eichman, the man responsible for trafficking humans to concentration camps across Europe, stood trial in Jerusalem, Israel.

Thus, Lasansky’s “The Nazi Drawings” were created. Over several years, he created a collection of 33 life-size illustrations showing the brutality of the Nazis. He used the most accessible mediums — pencil, paper, and other found items.

The collection was first shown at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Silence filled the gallery as onlookers gazed at the raw, untampered, and unrestricted depictions of the genocide that had happened two decades earlier.

In 1967, at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, lines wrapped around blocks to view Mauricio’s work.

Nearly 1,500 people would be admitted to the gallery daily to experience the collection. Mauricio Lasansky portrayed Nazis as they were — killers. His figures were donning skull helmets with teething visors consumed by death and destruction. Suffering women and children were focal points of the collection.

The objective of the work was to not only show the devastation of the Holocaust but also to serve as a warning of the possibility of an event like this recurring. And to Mauricio Lasansky, the illustrations were motivated by a deep fight against fascism and antisemitism.

“If you grew up as an artist during wartime, the perspective was if you chose to do art over working, manufacturing, or fighting in the war, it better be important,” Diego Lasansky, Mauricio’s grandson from the Lasansky Corporation Gallery in downtown Iowa City, said.

Today, the Lasansky Corporation keeps Mauricio Lasansky’s legacy alive through cataloging, preserving, and distributing work to museums. Diego Lasansky is continuing his grandfather’s legacy through this studio space.

“When he retired, part of the goal was to have studio space still in Iowa City,” Diego Lasansky said.

Mauricio Lasansky was born in Argentina in 1914. His parents were Eastern European Jews. His father was a talented printmaker and engraver who worked at the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia.

Beginning to pursue music, he was involved in the arts from a young age. Eventually, his father became his instructor in printmaking: the medium that would define his career.

In the 1930s, Mauricio Lasansky established himself as an important artist in Argentina. At 22, he became the director of the Fine Arts School at Villa Maria College.

But as Mauricio Lasansky’s star rose, former President Juan Perón consolidated power and set the stage for a dramatic clash between art and authoritarianism in Argentina.

Perón’s administration began closely monitoring artists to control cultural expression and censor their work. He viewed art as a potential threat to his regime’s authority and the unified Argentine identity he sought to promote. Mauricio Lasansky, outspoken in his criticism of the government, felt the weight of their scrutiny on his every move.

spread throughout 20 pieces of kneaded paper on display. Each one marks a live lost from the conflict. (Ava Neumaier)

In 1943, the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Director Francis Taylor first saw Mauricio Lasansky’s work. Taylor led him to his first of many Guggenheim Fellowships and a way out of Argentina.

In New York, Mauricio exposed himself to more art than he could imagine. Having access to the MET Print Archive opened his world. Enveloping himself in the works of Renaissance printmakers like Albrecht Dürer, inspiration grew. In his new vibrant art communities, Mauricio Lasansky was first exposed to Pablo Picasso. “As soon as a young artist sees Picasso for the first time, [they] get influenced,”

Desperate to keep making art and stay in the U.S., Mauricio Lasansky searched for more opportunities. His search brought him to the University of Iowa.

The UI had held status in the art world as one of the first state institutions to offer a Master of Fine Arts degree. In 1940, Elizabeth Catlett was part of the first graduating class and the first African American woman in the world to earn an MFA. Before the university adopted the MFA program, artists hailing from marginalized communities scarcely had access to outlets of artistic expression.

“[Catlett] spent a significant formative period of time in Iowa City doing her Masters of Fine Arts degree,” Diana Tuite, the visiting senior curator of modern and contemporary art at the Stanley Art Museum, said.

While a platform was given for artists, the realities and lack of civil rights still were apparent. Catlett’s practices and depictions of the Black experience through sculpture and printmaking were the foundation of the rise of politically driven work in Iowa City. As World War II ended, thousands of young G.I.s returned to college campuses. Many sought outlets to express the atrocities they saw during their service and promptly turned to Lasansky’s printmaking class.

“The [printmaking] process means that your art typically is more available. It’s a little cheaper, more of the general public can have it,” Diego Lasansky explained.

Mass distribution was not Mauricio Lasansky’s goal. His pursuit of advanced techniques pushed the boundaries of the field. A printmaking renaissance was happening in Iowa City.

“If you go to the late 1950s, any professor in printmaking was a student of my grandfather’s or of an Atelier 17,” Diego Lasansky said. “By the early 1960s, Iowa City and the University of Iowa became the printmaking capital of the world.”

Works from the Lasansky family can be seen everywhere in Iowa City. From the public library to the Java House coffee shop, prints from Mauricio Lasansky and his grandchildren are fixed proudly on the walls.

Depictions of great thinkers like Abraham Lincoln are shown in portraits to inspire a new generation of artists.

RELATED: Free expression on full display after one year of war in Gaza

“[Mauricio Lasansky] thought of himself as a humanist, and he thought of art as being that,” Diego Lasansky remembers. “A voice for the people.”

Although both the Holocaust and the creation of Mauricio Lasansky’s work took place over 70 years ago, the idea of using art to cope with tragedy has continued into the present. From Russia invading Ukraine to the attacks in Gaza, our world today has many subjects for this kind of work.

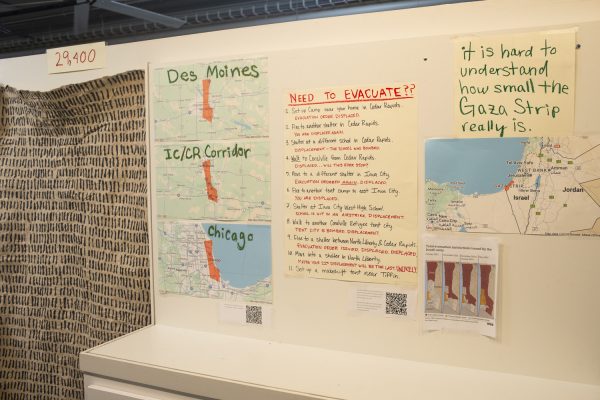

One of the most discussed conflicts of the present day is the Israeli-Palestine conflict. With the violence worsening by the day, more and more creatives are using art as both an outlet and a call to action. Clara Reynen, a third-year graduate student in the dual library science and Center for the Book program, is a prime example of an artist using their talents to showcase the loss of lives in the Gaza Strip.

incorporated drawings, poetry, and physical media. Following World War II the University of Iowa had a print-making

renaissance. Many artists at the time expressed the horrors from the war through their art.. (Ava Neumaier)

Titled “I Will Not Look Away,” Reynen marked tallies for each individual who has died so far due to the conflict on 20 large sheets of kneaded paper. Each sheet contains 2,100 tally marks, totaling 42,000 tallies over the 20 sheets.

Reynen isn’t the only artist bringing attention to Gaza through her work. Palestinian artists are expressing themselves through political art, as well as those who are not from Palestine but are still concerned.

Jordanian-American artist Ridikkuluz has expressed his outrage over the topic through his work. His painting “Handala of Liberty” plays off the iconic Palestinian character created by Naji al-Ali and the Statue of Liberty. The original al-Ali character is a 10-year-old refugee with his back turned, but in Ridikkuluz’s version, Lady Liberty has her back turned.

While many artists use art to cope with what’s happening in Gaza, many others use it to call attention to the conflict and force people to confront what’s happening.

“I’m hoping that people can just take some time to see this, sit with it, and imagine, you know, all these tally marks are representative of people,” Reynen said. “ I hope people can understand the true scale of the destruction in Gaza.”

Although Palestine is over 2,000 miles away, Reynen has a special connection to the country and its people.

“Growing up, my family moved to a brand new town my freshman year of high school, and I didn’t know anybody. On my very first day of math class, I sat down next to someone who would become my best friend. Her family is originally from the West Bank, so I’ve always been really lucky to know a Palestinian family personally,” Reynen said.

“I’ve never met anybody who’s more generous or kind,” Reynen said. “[It’s] heart-wrenching to see all of these false narratives being pushed about Palestine, what it means to be Palestinian, and what it means to be advocating for liberation.”