The projector whirs as film stock unspools into chugging machinery and diligent projectionists strain to lug large metal containers across a cluttered room. This is a common scene in FilmScene’s compact projector booth, sitting right above the seats in Theater One.

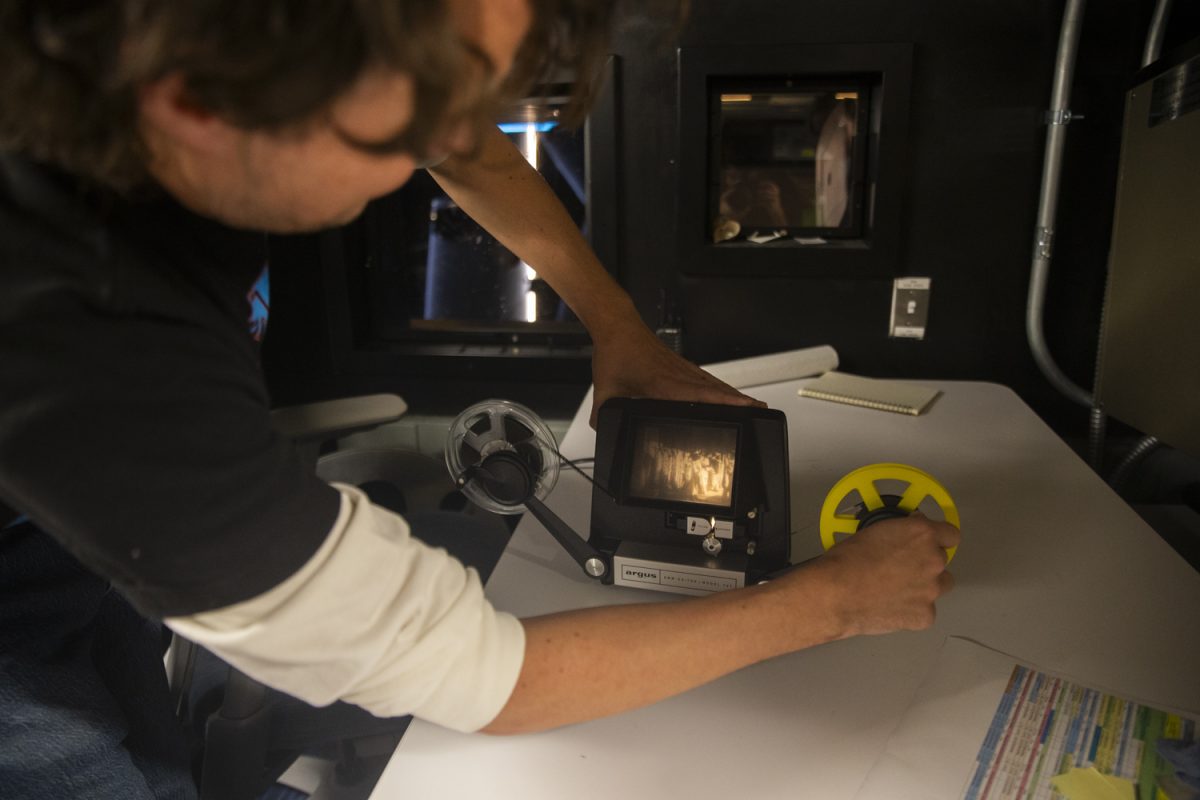

Hours earlier, FilmScene staff would have met delivery drivers to haul several film canisters in preparation for a showing. Before loading the reels into the projector, the cinema operator must scan the film print and note any discrepancies between distributor and recipient.

Much like when galleries transfer paintings, the distributor lists every degradation, such as scratches, on a film print for theater employees to ensure that nothing changes during transportation. Once the inspection is complete, the print can be prepared for projection.

“Each reel would be about 20 minutes of film. So, you load up reel one here and reel two there, and then you switch back and forth every 20 minutes,” FilmScene Head Projectionist and Facilities Director Ross Meyer said. “That’s basically the way projectors were from the beginning of cinema up until the 1980s.

In the 1920s, cinema became a staple in the American pop culture lexicon. Hundreds of film prints were produced and distributed to theaters nationwide every year only to be destroyed due to short-sighted reverence.

The Film Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Martin Scorsese, has estimated that half of American films made before 1950, and 90 percent made before 1929, have been lost forever.

In the 1980s, as the medium grew and became more profit-driven, theaters became even less delicate with projected films. Once handled by unionized projectionists, the 1980s mall boom created further preservation issues.

“You didn’t have trained people there keeping an eye on things. You had a high school kid who also has to run out and sell tickets or sweep up popcorn,” Meyer explained. “Film itself was thought of as much

more disposable.”

By 1999, upon the release of “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace” and the subsequent digital filmmaking revolution, 35mm film became obsolete across the U.S. Now, as digital filmmaking dominates, there are fewer and fewer dedicated projectionists.

But Meyer and his staff still love the intricate projection process.

Digitization wasn’t all bad. According to a report written by Jason Hellerman, the Digital Age ushered forth an era of film restoration. Today’s hi-def 4K DVDs and streaming services aren’t plagued by the dust physical film stock so readily attracts.

Janus Films, a restoration and distribution company, made it their mission to digitally restore deteriorating reels. Restoring films like Charlie Chaplin’s “Gold Rush” or Akira Kurosawa’s seminal “Seven Samurai” has made classics more accessible than ever.

Not only did this democratize the medium, but it also allowed theaters to more easily present important films the way they were meant to be seen — on the big screen.

This is FilmScene’s mission. From “Predator” to “Psycho,” the theater ensures its programming balances camp and challenge.

Repertory screenings, which is showing films after their initial release, have been a foundational aspect of the theater’s programming for over a decade, and the idea went mainstream during the pandemic.

“[Rep screenings] preserve art and culture, but it’s also important to share with an audience because the film is suited for that experience,” FilmScene Programming Director Ben Delgado said. “Seeing films in a theater is how creative teams want you to view those films, so preserving that legacy and sharing art with the community is important.”

In addition to preserving the experience, rep screenings recontextualize older films for modern culture. FilmScene’s recent “Hitch Girl Summer” series promoted Alfred Hitchcock films starring women.

Hitchcock had tumultuous relationships with actors, specifically women, famously stating, “All actors should be treated like cattle.” With decades of hindsight, audiences now view his films to analyze gender roles and representation.

In 2022, FilmScene was granted the rights to show the only existing copy of “Predator” on 35mm. In collaboration with the Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program, author Ander Monson spoke about the film.

Monson is the author of “Predator: A Memoir, a Movie, an Obsession” and uses the film to examine how white, male, mainstream culture shaped an era of life.

“Predator” prompts questions and critiques on fandom, masculinity, and general relationships with acts of mass violence.

“We feel it necessary to discuss the film and put it in context,” Delgado said. “It’s important for certain series we put on, especially if there is historically relevant context.”

Keeping old movies alive in the public consciousness services the films themselves and the audience. When exposed to older perspectives on storytelling, character, genre, and theme, viewers can begin to understand more about their place on the cultural timeline.

“You just kind of understand cinematic history more, and you learn how things sort of came to be,” Bijou Programming Director Ben Romero said. “I think by getting into older film, it’s just an enlightening experience.”

RELATED: FilmScene launches first annual Iowa Disability Film Festival

Since 1972, the Bijou Film Board has focused on screening important, challenging films that are free for students.

“I want to challenge student audiences and broaden their idea of what film can be,” Romero said.

Our generation of movie-goers grew up with streaming and on-demand films.

Viewers can become overwhelmed by the unlimited options and second-guess their decisions, creating unsatisfactory viewing experiences.

By eliminating choice, the theater setting becomes an important factor in exposure.

“When you’re in the theater experiencing the film like audiences in the day [they] experienced it, you’re just more in tune with the movie,” Romero said. “There are fewer distractions, which is important for older films that move at a different pace than today’s blockbusters. Many people don’t have the attention span to sit through films like these, but the theater pushes you to participate with the whole film and not just be a passive viewer.”

Even if not every film can be projected on 35mm, the effort of screening old films digitally is still healthy for the filmgoing population.

On the occasion FilmScene does project a movie on film, though, the results are pure.

“When you watch something on film you understand the physicality of it, you can see the film grain,” Romero described. “You see the filmmaker’s intentions more clearly. It’s a different way of watching a movie than just clicking ‘play’ on a streaming service.”

Seeking out 35mm screenings is worth it not just for the historical value, but also for the aesthetic differences.

“These films were shot on 35mm and were meant to be exhibited that way,” FilmScene projectionist Harry Westergaard said. “The colors are much more crisp on film. The darks are darker than you would ever see on digital. When there is a black screen, you can still see pixels on a DVD, whereas on film it’s dark, just true black.”

Meyer’s old-school love for 35mm projection places him on the front lines of the film preservation fight. Projectionists like Westergaard are brought up under Meyer’s mentorship and eventually leave FilmScene to bring their reverence to institutions nationwide.

“I’m always training new people, but the silver lining is that I’m sending these people with this new skill out to the world,” Meyer said. “I feel like I’ve somehow inherited this responsibility where I’ve accumulated this knowledge, and now it’s my job to pass it on to the next match.”

Responsibility is a key characteristic of the job. Film stock is delicate, and distributors don’t entrust their historic films to everyone.

“The time we played ‘Top Hat’ we used a Library of Congress print. They said nobody except for Ross could touch the print,” Westergaard recalled. “Sometimes they’re strict, [these films] were filmed on 35-millimeter and meant to be exhibited this way.”

The mission of the art house cinema is to exhibit film’s most historic offerings the way they were meant to be seen — but audiences have a mission, too.

It’s impossible to understand the present film landscape without first contextualizing where it has been.

With the efforts of preservationists, film history has never been in safer hands.

“If I get hit by a bus tomorrow, at least my film collection is here,” Meyer said. “[It will be] surrounded by other movie people who presumably will know what to do with it and keep it safe and keep playing it for audiences.”

Arts Editor Charlie Hickman also serves on the Bijou Film Board.