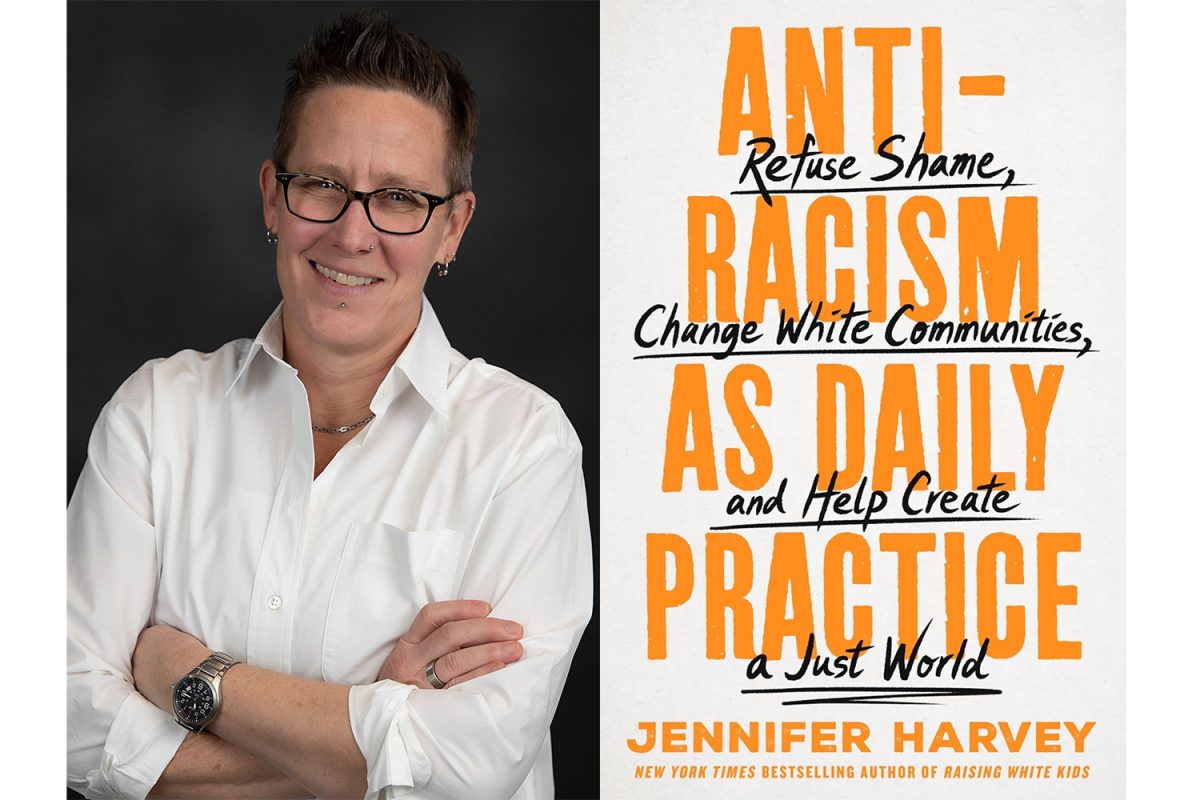

Jennifer Harvey is an award-winning educator, public speaker, and author of The New York Times bestseller, “Raising White Kids.” Her new novel, “Antiracism as Daily Practice: Refuse Shame, Change White Communities, and Help Create a Just World,” was released in July. She has written for CNN, The Conversation, HuffPost, Sojourners, and more.

Harvey is currently the Vice President for Academic Affairs and Academic Dean at Garrett Evangelical Seminary, where she also teaches classes in Christian ethics. Before this role, she was the Faculty Director of the Crew Scholars Program (an academic excellence and leadership development program for students of color) at Drake University. Harvey currently lives in Des Moines, Iowa, and Chicago, Illinois, with her two children.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Daily Iowan: In the introduction, is there a particular reason why you decided to include three different anecdotes with Ruth Sandhill, Lisa Johnston, Dave Smith?

Harvey: Initially, my first draft didn’t start with any anecdotes. My editor wanted me to start with some stories so that more folks could feel more brought into the book. I didn’t start like, “Let me do three,” but those three stories captured major themes and examples that I take up later in the book. I think it was as much about three concrete examples that I thought folks might recognize. Then, I would be able to offer some insights, ideas, and engagement throughout the book.

What did you mean when you wrote, “And there’s certainly no clean path to becoming better white people, no guaranteed way to avoid all mistakes, complexity, and messiness”?

We [as white people] have a lot of anxiety and concern that we’re going to do it wrong or make a mistake or speak about race in a way that’s offensive and harmful. I deeply believe that it is impossible to avoid making mistakes. We are responsible for doing our own work so we reduce the likelihood of harm with the mistakes that we make. Recognizing we’re going to make mistakes [is] the only way that we’re going to grow. [This] is important to get more white folks to be willing to take the journey [toward becoming better].

To add on to this, was there an interview process, and how exactly did you choose which of these individuals’ experiences to include in the beginning?

No, there was not a process because all three of those stories are about people that I know and/or have worked with. I was writing from my own experience of what I bore witness to or knew about. I had been in some kind of relationship or friendship or working space with those individuals.

[I wanted to share] the Ruth Sandhill story because it shows a step-by-step growth process, and a lot of white folks need that to see what it looks like to grow your commitment in terms of your daily skillset.

[I wanted to include] the professor’s story because it both names his anxiety at this moment where he realizes though he understands the stakes for belonging and the experience of inclusion that comes when he might not remember the student’s name. His whiteness is also getting kicked up because he’s like, “Oh, my gosh,” and “I don’t remember the students’ name, I might get it wrong.” I suspected other white folks would resonate with that anxiety, but also his story helped me ask the question, what is his role in making an institutional, organizational space more inclusive?

I [also] wanted to include the [Lisa] Johnston story because [of] that problem when white folks want to take action but then also know that it’s so easy for us to mess it up so powerfully. We can get better at this, even though you can see how complicated her situation is and probably resonate with it.

If you think there is a clear-cut way to solve the debilitating aspects of racism, what would it be?

So, I don’t think there is a clear way, but I think there’s a whole long list of practices and changes and structural interventions that we could come up with. If I was getting to design it with others, I would be like, “Well, we’ve gotta have consciousness-raising education around the actual history of the U.S. because white supremacy and colonial settler realities are interwoven into the existence of this nation-state.’ We could design structures of repair. It’s a massive generational project.