Charles Holdefer is a Pushcart Prize-winning novelist and short fiction author. His short fiction has appeared in dozens of magazines as a writer. His catalog of satirical stories has garnered praise from Publishers Weekly and the Library Journal. Holdefer grew up in central Iowa and attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

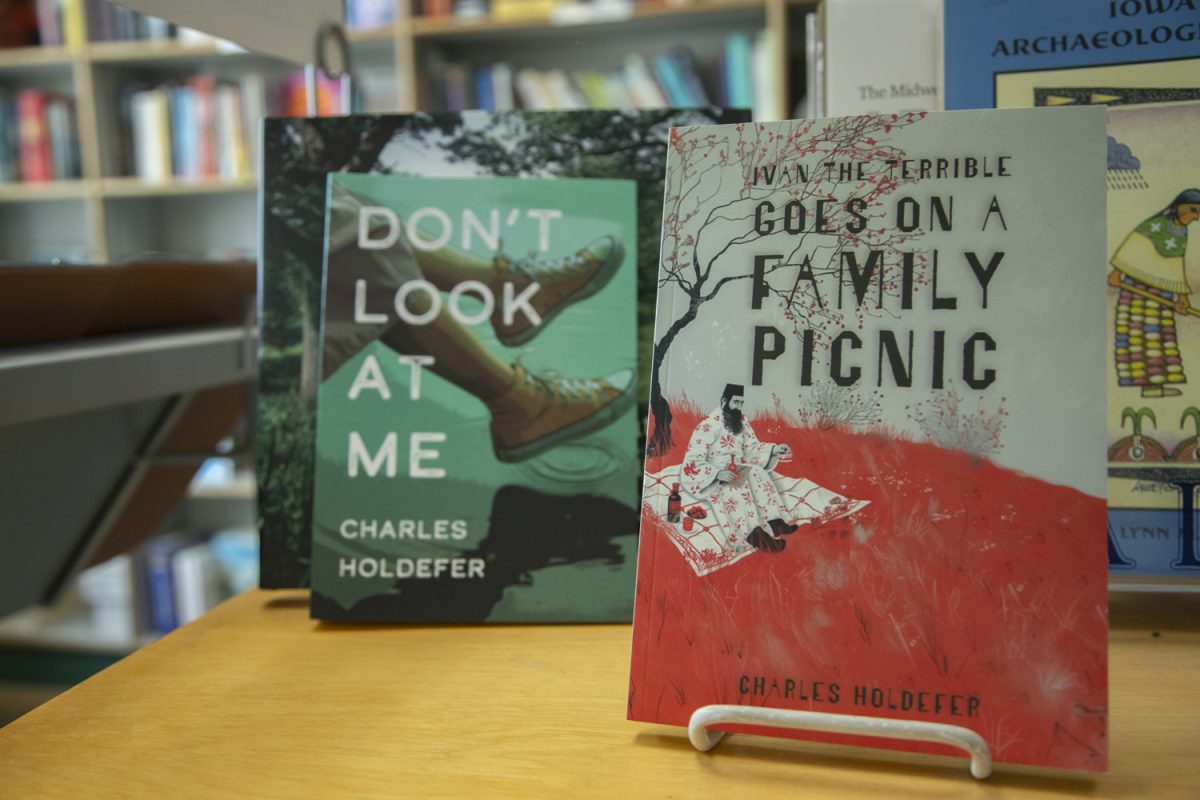

His upcoming short story collection is titled “Ivan the Terrible Goes on a Family Picnic” and explores a myriad of concepts through the world of baseball. Holdefer’s speculative fiction sports stories ponder the connection between Babe Ruth and French writer Gertrude Stein, whether or not baseball was invented in Russia, and even what baseball tells us about the afterlife.

Holdefer will read from his collection at Prairie Lights Bookstore on Monday, Jul. 15.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The Daily Iowan: How did you come to the Writers’ Workshop?

I grew up on a farm, so going to Iowa City was like going to the big city. I always liked to read, and writing seemed to be a natural extension of that. And then while I was at the University of Iowa as an undergraduate, I heard about the workshop. It seemed like fun, and I felt the main reason to write was to participate in the conversation. That’s what I tried to do, so a few years later I became a student of the workshop, which was a great experience.

How did teaching and living abroad help your writing?

I went to France after graduating from [the Iowa Writers’ Workshop] thinking I would only be there for a year to write. Then I managed to stay one more year. And after years of saying that, I put down roots. I lived in France for 20 years, but now I’m primarily based in Belgium. I taught for many years at the University of Poitier in France. Students — most of whom were francophones, not anglophones — I was teaching them literature, and it’s not the same as teaching native speakers. It made me look at language a little differently. Living around other languages … obliges me to slow down and pick apart words a lot. And I didn’t do much translation. Mainly I taught direct literature, but I think any foreign language experience is a good thing for any writer.

“Ivan” is a very satirical story, in line with most of your writing. What draws you to that tone?

It’s not so much a conscious choice; that’s just the way it comes out. One thing I noticed, which I wasn’t conscious of immediately, was that perhaps short fiction dialed up the satire a bit more strongly. It’s a bit more removed from the realistic convention, whereas the longer form — like recently I had a novel come out called “Don’t Look at Me,” and there are some satirical elements there, but that is kind of straight-up realism. Somehow the shorter pieces tend to be more satirical, though I have also had some longer things that are kind of satirical too.

When you plan a project, how do you determine if it will be a novel or a collection?

Boy, I don’t know. Honestly, I’m not a meticulous planner. Some people really map out their books a lot. And there are pros and cons to that. I mean, the risk of not mapping out things enough is you can take a wrong turn and then later have to throw away 50 pages, which hurts. My first novel was a short story in the beginning where the narrator just would not shut up, and then I realized there’s a longer story there and was free to expand it. The difference has to do with realistic detail and the sense of an imagined world. With a short story you are diving into a pre-existing world where you don’t have time. You’re creating the world more by suggestion. The short answer is … a narrative impulse comes. And once I start trying to follow it, it tells me how long a story can go on.

Do you have a research process for your more historical stories?

A couple of stories do have some real research — most of it is probably what you’d call speculative fiction, though. On previous books, I did a lot of research on Emily Dickinson and had to be a bit more careful and more judicious maybe with the short stories. It’s just making sure I get certain things right, but “Ivan” is not like a research-heavy book, and the stories take place against a backdrop of baseball. But it’s not like other so-called sports books. It’s not about how our team won the big game or something like that. It’s more allegorical in certain stories. You don’t have to like baseball to find this book interesting. The idea didn’t come from research but rather from a story I wrote a while ago about a baseball team in Paris. It’s a fish out of water story, and a guy said to me, ‘Well, you should do some more baseball stories.’ Eventually, enough stories emerged that I could put them together into a book.

Is there a purpose to the ordering of stories in the collection?

For most story collections, yeah, how you order them … that’s a headache, yeah. You’re trying to take smaller pieces and at the same time have a larger thematic coherence. It feels nice in “Ivan” because the stories are chronological. It starts in the 16th century with Ivan the Terrible, and the last story is in 2022 — it’s contemporary. So that’s kind of the arc of the book to the extent that, one, it’s chronological, and the reader dips in and out of different periods. And so you see, you know, the fanciful stuff about Ivan the Terrible. But then there are more realistic fiction portions, and it all centers on baseball.

What did you learn from the years in your early career submitting stories to magazines?

Make sure it’s finished. Don’t send it out too soon. For instance, I’m an editor of a rather obscure fiction magazine. One thing I notice when I read a bunch of submissions is that some pieces are just inappropriate. We’re a magazine that publishes a certain type of fiction, maybe a little bit more on this experimental end, but we do some straight-up realism too. And so then if someone sends us a story that is like a Western or a romance, you’re just submitting blindly. You ask yourself, ‘What kind of story am I writing?’ Submit to magazines that are doing a similar kind of thing to you. My last thought would also be don’t have thin skin. Don’t get too upset about rejection because it’s just normal. It’s part of the game.