The University of Iowa is renowned for its excellent writing program, churning out countless award-winning novelists, nonfiction authors, and playwrights from the writers’ workshop.

But fan fiction writing often goes unrecognized, and even dismissed, for its pivotal role in the development of young writers’ voices.

For many people, the genre itself evokes a stereotype: superfans who create written spinoffs of fiction books or movies out of obsession, often containing taboo takes on beloved fictional characters.

Writers are aware of this, but the reality could not be further from this misconception.

“To say the entire category of work is one thing is a little funny to me,” Darrin Terpstra, a UI fourth-year creative writing major, said.

Terpstra has been writing fan fiction since he was a preteen. His story is similar to countless fan fiction writers who grew up with internet sites like fanfiction.net, Wattpad, and Archive of Our Own, commonly known as AO3.

For him, fan fiction offers an escape from the restraints that come with career writing.

“I had watched a movie, which I can’t remember at this point, and I didn’t like how it ended. So I wrote this probably terrible short story and changed the ending,” Terpstra said. “I was reading stories like mine for like three weeks until I realized it was fan fiction.”

Fan fiction can be an original work featuring characters from preexisting properties, expansions on fictional universes, sequels, prequels, or anything in between.

“I get tired of seeing some storylines play out the same way through so many different works. When I watch or read other works, I end up seeing things I wish could have happened,” Terpstra said. “I think I’m an impatient person. I don’t feel like waiting for someone else to write further stories with characters I’ve grown passionate about,” he joked.

UI second-year creative writing student Thalia Eliazar shares this sentiment.

“The worlds that were already built that I was reading about—I felt interested in expanding them,” Eliazar explained. “[I liked] exploring new characters and the politics and sort of relating it to real stories in our world,” she added.

Eliazar had been a reader of fan fiction since she was young, but it wasn’t until 2020 during the COVID-19 lockdown that she tried her hand at writing her own. She cited the sense of online community and their promotion of the creative outlet as the reason the genre intrigued her.

“It didn’t occur to me that I could write it until I was older,” she explained.

Before AO3’s time, Terpstra explained that fan fiction could be found scattered across the internet on various forums, websites, and messaging boards such as LiveJournal. However, the history of fan fiction pre-Internet is much richer.

The history of fan fiction

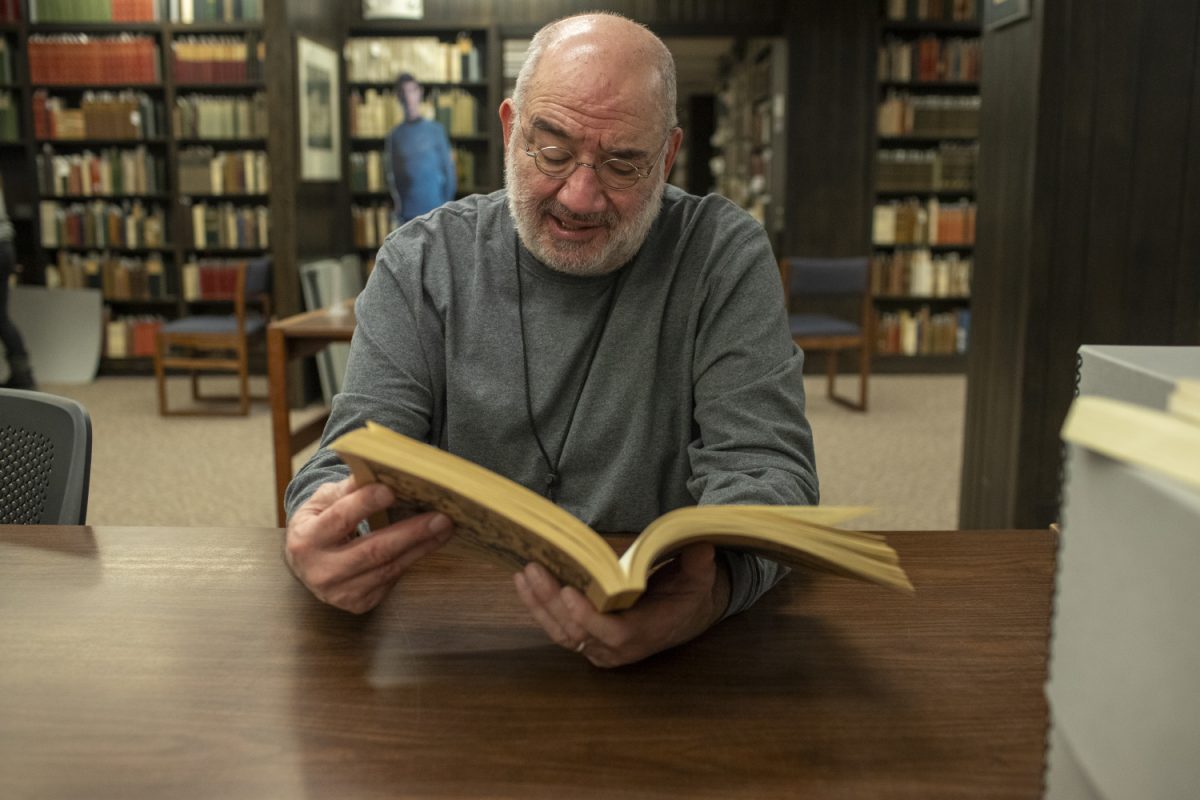

Before the digitization of fan fiction, publications commonly referred to as fanzines — a combination of fan fiction and a magazine — could be found at any magazine stand. Peter Balestrieri, the curator of science fiction and popular culture at UI’s Special Collections, is an expert in fan fiction.

“Fan fiction as we know it today really started in the 1960s with ‘Star Trek’ and ‘The Man From U.N.C.L.E.,’” Balestrieri said.

Much like today, fan fiction was published by groups of passionate fans and whole communities that have since been coined “fandoms.”

“The history of fan fiction is the history of self-publishing,” Balestrieri explained. “Self-publishing was how poets like Walt Whitman were able to put their work out when they were just starting.”

Balestrieri identified fiction author Ray Bradbury, best known for his book “Fahrenheit 451,” as someone who got his start writing in fan magazines.

Further, the author of the infamously R-rated book-turned-movie “50 Shades of Grey”, E. L. James, wrote her first drafts as part of a fan fiction series based on the wildly popular 2008 vampire movie “Twilight.” James is now regarded as “the most commercially successful fanfiction author of all time,” according to a Forbes article from 2017.

Without a digital platform for fans to constantly express their shared passion for their favorite shows, fan clubs and fanzines reigned supreme. Since print publications were so readily available to buy at stands, anybody could pick up a fanzine and become inspired to write their own spin-off Star Trek stories starring Captain Kirk and Spock.

Now, with accessibility at the forefront of popular fan fiction sites — and social media sites like Tumblr and X, formerly known as Twitter — creators are much more involved in their fandom communities. In terms of authorship, the much-debated topic among fans led to questions over the legitimacy of fan fiction.

“You have people like George Lucas who resent fans creating their own adaptive works but creators like Gene Roddenberry who embrace it,” Balestrieri said. “Star Trek only survived because of the fans.”

Passion from fans has always been a driving force behind making fan fiction accessible, whether it be through physical publications or digital archives. As someone who aided in the curation of one of the largest physical collections of fan fiction in the world, Balestrieri is one of those fans.

“A lot of students don’t know that the University of Iowa is a hub of fan fiction,” Balestrieri said.

The Organization for Transformative Works, the parent company of Archive of Our Own, has partnered with the UI since 2009 to form a preservation alliance. The UI provides a physical space for the OTW to house its historic collections of fanzines and fandom content.

“Through our partnership with the [OTW], we’ve received hundreds of collections of historic fan fiction,” he shared.

A large portion of fandom content is novels, stories, and fanzines. However, fan art is an equally important entry in fan content archives.

“I had just started learning how to draw with Mario characters and Overwatch, with properties I was already passionate about,” Robert Rysz, a UI second-year student who has been drawing fan art since the sixth grade, said.

Rysz’s artwork is directly influenced by the anime and manga he loves. Just like fan fiction writers, fan artists are directly driven by their passion for the stories they read.

“I kind of make it for myself,” Rysz explained. “But I’m very involved with the communities of the fandoms I make fan art of.”

In both mediums, however, sharing work with fellow fans can add a layer of pressure, especially when your work lands in the laps of thousands, even millions, of other users.

“The first story I put online reached about two million readers,” Eliazar recalled.

Eliazar’s fan fiction, based on the popular anime series “My Hero Academia,” had reached beyond the website on which she published it. One random reader brought her story to TikTok, and their video went viral.

“I was just sitting at the dinner table and my phone was blowing up like ‘Your story has 100,000 reads, your story has 200,000 reads,’” Eliazar said.

It may be hard to pin down exactly what fan fiction can be, but it has captured the imagination of aspiring writers for decades. However, Eliazar shared that the internet’s

biggest misconception surrounding fan fiction is that it’s all “cringe.”

“Sometimes it is, but I think just like any other kind of writing, there’s variety … It’s how a lot of young writers get their start,” she said. “A lot of powerful stories can get brushed aside just because of the form of writing.”

Fan fiction will continue to be a popular outlet for creative people to express their passion. Balestrieri believes young writers will continue to be inspired by fan fiction.

“We bring classes [to Special Collections] every week. I love watching young writers look around a classroom and realize they aren’t the only ones involved in fandoms,” Balestrieri said.