John J. Waters graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy with a degree in English literature in 2009. Not long after, the Nebraska-born author served in the Marine Corps for nearly seven years. A week after he returned, he began studying law at the University of Iowa.

The process of writing his newest novel, “River City One,” carried him through some of the darkest years of his life post-discharge.

Published by Simon & Schuster, Waters’ Roman à clef tells the story of John Walker, a veteran who struggles with facing himself after returning home from war to a nameless city where an unlikely love interest reignites his passion for life.

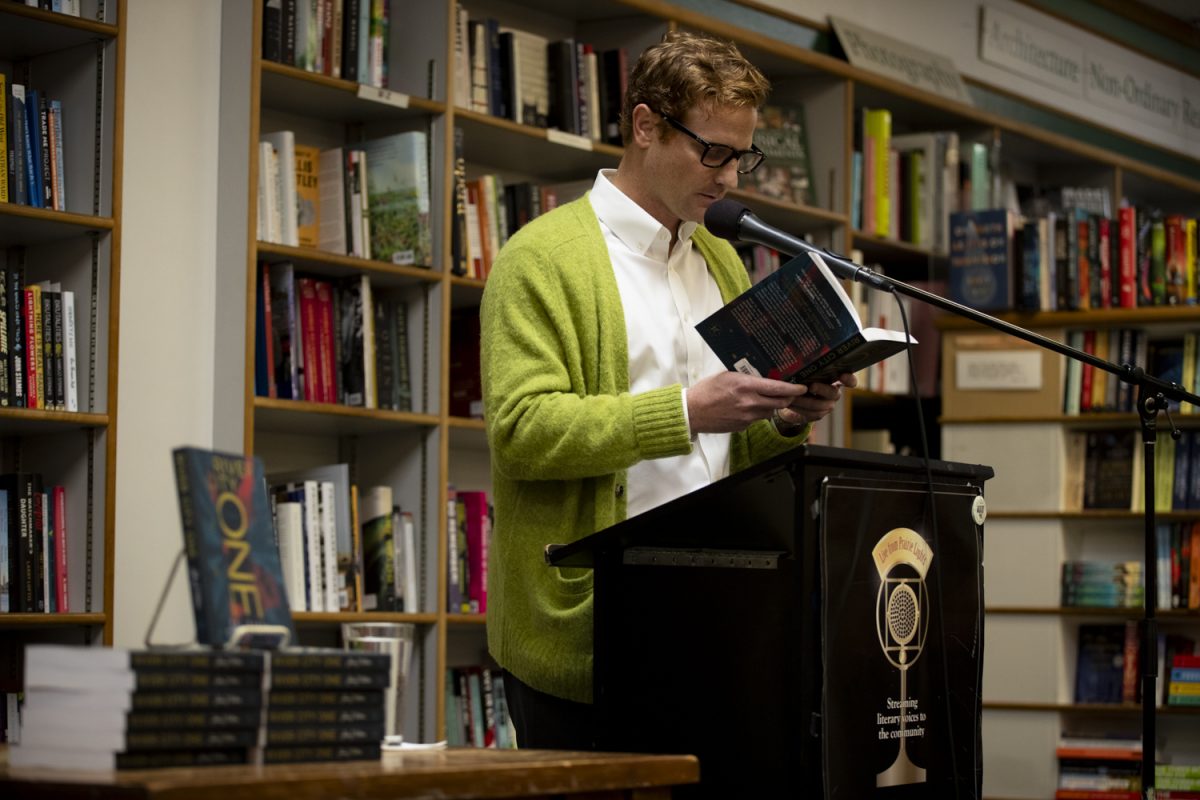

Waters read from his novel at Prairie Lights bookstore in Iowa City on Nov. 8. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Daily Iowan: What inspired you to begin writing “River City One”?

John J. Waters: 2019. I was at a party in Omaha, hosted by a lawyer. There was a singer there from the opera. She spoke about this upcoming performance of Philip Glass’ opera, “Les Enfants terribles,” and after she finished speaking, there was a man in the back and he said, “Why don’t you sing for us? You’re a soprano.”

She seemed embarrassed, but she sang “Danny Boy.” I was leaving that evening, and she stopped me, and we started chatting. She told me the song is about a mother watching her son go to war. I told her that I had gone to war, and she asked something like, ‘Does a soldier come home from war?’ And I didn’t have an answer for her. I started writing shortly after.

The city in your novel is nameless — what is the significance of this decision?

To make it representative of any city. I think a lot of people have “river cities.” There’s one New York, there’s one San Francisco, there’s one Washington D.C., there’s one Chicago, but there’s a lot of “river cities.” I wanted this to be a nameless place, I didn’t want it to be about Omaha. I wrote about what I knew — parts of myself, parts of where I’ve lived, but the novel wasn’t entirely autobiographical. When I wrote it, I extended what I imagined it could be.

With your military background, what unique perspectives do you feel you bring to the literary conversation about war and its aftermath?

To me, the story began when we came home. To date, there have been many stories written about conflict — stories about coming home are emotionally rich and complicated, and they center on the family that bears a strain that I think has yet to be fully illustrated or penetrated. Further, the minds of veterans had not yet been penetrated to the extent I tried to in this book. I really liked Ben Fountain’s book “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” and Roxana Robinson’s book “Sparta.” Each tries to illustrate the coming home story — the military veteran in society — but those authors are not veterans. However, they imagined it in a way that was very, very incisive. That’s where my mind went in writing the story.

You’ve mentioned the challenge of coming home to face yourself after war. How did you approach writing about this psychological experience?

Through writing. I would write this book late at night. After work, after I put my kids to sleep, I would go into my basement, and I would write. I wrote it with a pencil the first time until midnight. Then, I’d have to get up early for work the next day, but it made me feel very alive, very excited in a way that I wasn’t feeling otherwise. And that to me was a signal to keep going, to keep doing it. Writing this novel reignited me.

What do you hope that readers, especially fellow veterans, take away from this book and the story of John Walker?

I hope people can be open to it. I don’t try to judge the character, what he does or what transpires. I don’t have an argument to make about war or love or even about family. I wanted to depict and illustrate something comprehensively, and I hope readers can be open to it and extend from it their own conclusions.