Hawks, other raptors attend games at Kinnick to boost conservation education efforts

Through a partnership with University of Iowa Athletics, the Iowa Raptor Project brings live raptors to football games to emphasize the importance of conservation and add a new game day tradition.

A hawk from the Iowa Raptor Project rests on a handler’s hand during a football game between Iowa and Kent State at Kinnick Stadium on Saturday, Sept. 18, 2021.

October 12, 2021

Fans may have noticed more than one bird, besides Herky, present on Duke Slater Field this football season — two red-tailed hawks and a peregrine falcon have joined the Hawkeyes.

Game day is filled with traditions for the Hawkeyes: the Wave after the first quarter, the team walking out to “Back in Black,” and Herky running around the field getting the crowd fired up, to name a few. But a new tradition will soon be added at Kinnick.

But the newest tradition to be introduced to home games has been the presence of live hawks and other raptors as a part of the Raptor Ambassador Program, a partnership established between University of Iowa Athletics and the Iowa Raptor Project.

The partnership promotes conservation and brings awareness to the work of the Raptor Project by showing off the birds to thousands of fans gathered on Saturdays.

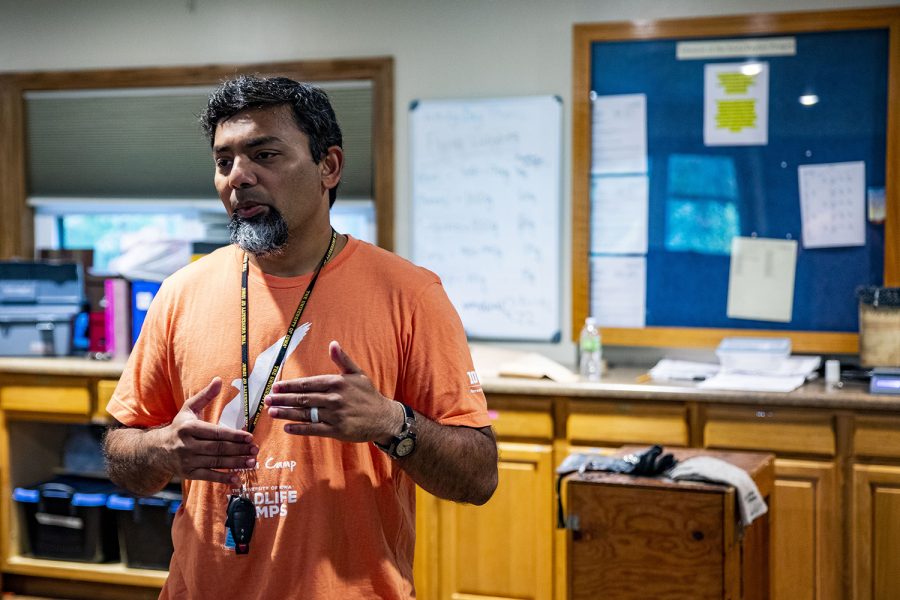

“Iowa is the Hawkeyes’ State, so it was very easy,” said Ryan Anthony, a master falconer and director of the Iowa Raptor Project. “At some point before [this year], me, [UI] Athletics, and people involved with the Iowa Raptor Project were talking about ‘Hey, what would this look like, getting a bird out to the games, or several birds maybe?’ This year, we finally had the opportunity to get started.”

The project hopes to eventually have one of the birds — a female red-tailed hawk named “Hercules 2,” after Herky the Hawk’s full name — fly from the press box down to a trainer standing on the field. The flight will take place during pregame, after Herky has taken to the field and before the team emerges from the tunnel.

Kelsey Laverdiere, assistant athletic director of marketing and fan engagement, has been working with the Raptor Project for three years to get live hawks at athletic events.

A variety of raptors will gradually be introduced to the Hawkeye fan base, Laverdiere said, and she hopes to highlight as many birds of prey as possible.

Hercules 2 was selected as the bird to train for flying because of her consistency and ability to learn quickly, said David Conrads, director of UI Wild and supervisor of the Iowa Raptor Project. As a female raptor, Hercules 2 is also larger than male raptors, he said, and as a dark morph red-tail, her feather pattern is rarely seen in Iowa.

Laverdiere said she doesn’t believe having Hercules 2 fly this year was necessary, but the raptor was doing well in training and now the future seems “limitless.”

However, with only one eye, the female red-tail’s vision is limited, Anthony said, which can make flying difficult.

While the trainers in the Raptor Project have worked with Hercules 2 for four weeks on the flight, a lot of factors go into determining if it’s safe for her to fly during a game.

Weather, the bird’s weight, and her behavior that day are the main determinants, Anthony said. Anthony and his wife Holly, another master falconer and assistant director of the Iowa Raptor Project, can sense when something is off with Hercules 2, and may decide it’s unsafe for her to take flight.

The birds are trained using a food-reward system and trust-building between the bird and the falconer. The bird is repeatedly called to the trainer — specifically to a lure made of leather tied to a rope with meat attached to it, Anthony said.

Given the bird’s fast metabolism, the trainers must be careful how much or how little they feed the raptors, he said. Anthony weighs Hercules 2 daily to make sure she stays a consistent weight and won’t be weighed down as she flies.

Other raptors introduced to the program so far are Hercules 3, a male red-tailed hawk and the brother of Hercules 2, and Tigerhawk, a peregrine falcon.

All three birds have made appearances on the field prior to games to acclimate them to the crowd.

“The big thing that’s really critical is that these are not mascots, these are most certainly ambassadors,” Conrads said. “Herky is a mascot, these birds are not like that.”

The partnership exists to help educate people on the raptors that share Iowa as their home and place emphasis on the importance of conserving raptor habitats, he said.

Having red-tailed hawks at the games felt like a good fit because they’re native to Iowa, Laverdiere said. Red-tailed hawk nests can be found all over the UI campus.

“They’re just part of our day to day, and [we] want to highlight them and make it a special group effort of educating others,” she said.

While only three raptors have made appearances at games, all 17 of the Iowa Raptor Project’s birds are raptor ambassadors.

Nestled out on a peninsula off Lake MacBride in Solon are the facilities managed by the Iowa Raptor Project. Chirps, squawks, and screeches greet visitors as they walk around looking at the different birds of prey the project cares for.

The facility, which opened 35 years ago, logged 44,000 cars entering and leaving the facility in 2019.

The birds cared for by the Raptor Project are either injured, have a mental handicap, or were purchased for programs that promote conservation, Anthony said.

The two red-tailed hawks were bred in captivity in Nevada and the peregrine falcon was bred in captivity in Washington state; all the birds were born within the last year.

The Raptor Project spreads its conservation message by conducting research on the wild raptors in the area and programming through partnerships with other local organizations, Anthony said.

The hope is that the Raptor Ambassador Program will last for years to come to continue educating people about conservation, Conrads said.

“This is built around that conservation education message that Iowa has wonderful farmland, but this land has also been more drastically altered than any other state,” Conrads said. “So, the importance of recognizing the conservation of habitats, that these birds are serving as icons to remind people of all those things.”