UI psychiatric professionals address mental health concerns around COVID-19

While coronavirus cases continue to rise across Iowa and the U.S., experts are addressing the psychological toll that mitigation efforts and the stress of a pandemic could have on mood disorders like depression.

The University Counseling Service is seen on April 16, 2019.

July 9, 2020

Though the long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health remain unknown and are evolving, psychiatric professionals are observing and anticipating exacerbated symptoms of mood disorders and other mental-health concerns as the virus and efforts to mitigate it continue.

Mark Niciu, an assistant professor of psychiatry and affiliate with the Iowa Neuroscience Institute at the University of Iowa, said he’s seen patients coming in his clinical work with COVID-related complaints, including increased sense of isolation, boredom, fatigue, and anxiety.

Complaints related to “the never-ending-pandemic,” mostly involve isolation and loneliness, Niciu said.

“I think especially as the winter starts rolling on and if this continues, I can anticipate continued stress and concomitantly symptoms of depression being criteria potentially for a major depressive episode,” Niciu said. “So I think this is going to be the fallout of COVID — when people feel a lot of psychiatric-related illnesses.”

People with extroverted personalities, caregivers, and those that have elders or children depending on them could face a large burden by not getting to indulge in their regular escapes during the pandemic because of mitigation efforts and social-distancing guidelines, Niciu said.

Niciu said that he thinks many of the typical recommendations for mental-health patients contradict mitigation guidelines.

RELATED: UI to host mental health online panel for student support during COVID-19

“For example, when I treat patients with a major depressive disorder, one of the things that I recommend, it’s called behavioral activation — so engaging into the community, exercise, planned activities, essentially structure their life so they get out of the house and do things that might augment mood whether that be exercise or interaction with others,” Niciu said.

He noted that uncertainty and financial burden could further affect symptoms of depression.

UI assistant professor Aislinn Williams said she expects increased levels of anxiety and depression within the general population amid the pandemic because of the added stress it places on everyone.

For people who already have a mood disorder that is worsened by stress – like bipolar disorder or depression – Williams said it is more likely for symptoms to come back and cause people to have an episode or be severely impaired under the increased stress of the pandemic.

Williams noted that part of the way humanity needs to cope with COVID-19 is the exact opposite of what psychiatrists would normally recommend to people struggling with a mood disorder — to self-isolate instead of going out.

“I think it’s important for us to think creatively about how to maintain social distance without creating social isolation,” Williams said.

Williams added that being proactive is essential to the nation when grappling with mental-health concerns, as the stress caused by the pandemic will likely last for the foreseeable future.

“…The mental-health toll of the pandemic has not hit its peak and is likely to continue in the long term and if we do not proactively try to help address the risk of depression and anxiety now, we may get to the point where the needs of the community for those mental-health resources are bigger than what we are capable of providing,” Williams said.

Director of the campus University Counseling Service Barry Schreier, said the UI has seen an “it depends” kind of response from the students it works with, based off of speculation and anecdotal data — as no specific data regarding mental health in relation to the virus is available yet.

RELATED: UI offers tele-mental health resources with campus closed to contain coronavirus spread

For some students who live with depression, COVID-19 has been terrible and increased mood problems related to an inability to have a regular schedule, see others, or engage in other externally focused activities, Schreier said.

Schreier added that some students have reported the opposite experience, noticing a reduction in mood concerns since the pandemic began, which may stem from not having the stress of going to class or constantly keep a smile on their face.

UCS was able to transition from in-person services to a virtual format almost seamlessly within a week, Schreier said, but noted that for some students being away from campus wasn’t necessarily better.

For example, Schreier said some LGBTQ students may have had to return to homes where their identities weren’t embraced like they are on campus.

Dealing with ambiguity, losses, and disappointments will impact students’ wellbeing and way of coping with the pandemic, Schreier said. He added the UI is currently preparing a COVID-19 mental-health postvention and recovery plan to serve as a comprehensive guide for students when they come back in August.

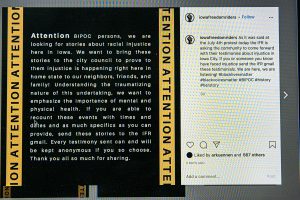

“Some people have a style that’s very flexible … and other folks don’t like all that flexibility,” Schreier said. “But I think we’re going to come into a fall semester while COVID is going on, there’s a lot of racial unrest that is erupting … and we have a big election coming up in November. All of these things are going to come together and really press on students, so it’s going to be so critical that everybody stay connected to their supportive networks [and] engage in good, well-being behaviors.”