Opinion | White America needs an art history lesson

Marking public spaces was an accepted artform of political expression in Western society for millennia, until racism deemed it vandalism.

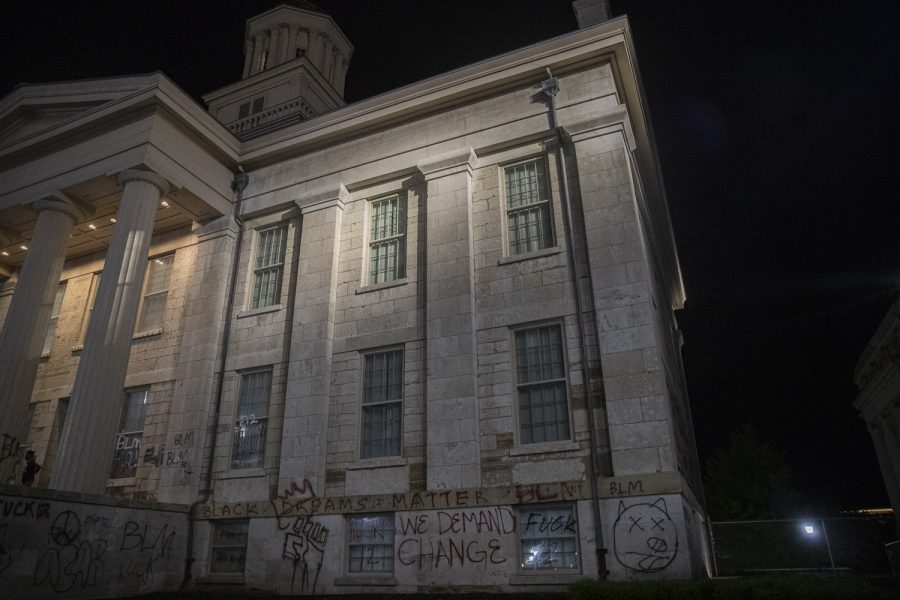

The Old Capitol in downtown Iowa City is seen after the completion of a march to support the Black Lives Matter movement and protest police brutality on Thursday, June 4. Protesters added to the graffiti from previous nights and small groups stayed behind after the crowd dispersed to take photos and continue spray painting.

June 17, 2020

As Black Lives Matter protests continue to leave their mark, it’s become obvious that many Iowans have forgotten – or were never properly taught – history.

What many are calling “vandalism” by protesters is in fact an ancient, very Western style of political expression. Painting public spaces, or graffiting them with words or images, goes back to the ancient civilizations of the Greeks and the Romans.

Much of the political and social concepts of these empires have become the foundation of contemporary white, Western culture – including our own. The irony then of condemning spray paint as a way of protesting for Black Lives Matter, is one that denies the history of political technique itself.

The word “graffiti” itself originally comes from a Greek word we would spell as graphein – to write. The first of these graffiti writings, usually scratched or marked into stone structures, are thousands of years old. They’re still read and looked at today. Studies by archeologists and historians show that these preservations of graffiti typically voice a social thought. It could be an expression of praise or reverence for a great war hero or god, or a political satire of a senator.

Black Lives Matter protesters are using graffiti in the same styles and intentions as these ancient civilizations.

If you go and stroll around the Pentacrest or downtown Iowa City today, you’ll see that’s exactly what has been spray painted. The names and portraits of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd are signs of respect and recognition for them, as well as calls for justice. “F–– 12” is, as objectively as possible, a rejection of an institution.

In the time of the Romans, this act — or way of protest — on structures or buildings was considered a social norm, and uncontroversial. It was simply a way a society communicated within itself. They certainly didn’t cause outrage. Even now, ancient graffiti are deeply appreciated artifacts; they help us understand how civilizations thought, wrote, and read.

But public view of graffiti has dramatically changed, easily within the last century alone. Graffiti now, particularly by the U.S., is seen as a kind of vandalism of property, or damage to a space. Definitely not as an historical art form.

One has to question why this view – America’s view – has changed.

Modern graffiti has very much become heavily influenced by hip hop culture – a Black and Latino art movement that began in the Bronx in the mid-1970s. Even some years before hip hop emerged, graffiti was a political and creative tool used by the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. So in American culture, graffiti has become an exclusive element of hip hop and Black expression, both artistically and politically.

Because graffiti has become more publicly associated with POC communities, it’s being condemned because it is now being used to amplify Black voices. That rejection has racist internalization. Public outrage is over washable paint on a building, rather than the institutions that are continuing to kill an entire people.

It’s not the art on a wall, or the form writing that’s no longer acceptable – it’s the Black writer.

What about these buildings, anyway? Prioritization of property over people – or even that people are forms of property – is also as historical as one can get in America.

What about a college? A building on a campus stands because it was built and paid for by those upholding education. Universities themselves have long been a core to social movements; evolutions of art, culture, and politics.

For there to be outrage that students protesting for Black Lives Matter are spray painting their own campus is an uneducated reaction. The reality is that graffiti is not destruction. It is a history of a public art form being used now, by a new generation of activists.

Instead of questioning why there is writing on the walls, ask why the writer wrote them.

Columns reflect the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board, The Daily Iowan, or other organizations in which the author may be involved.