University Counseling Service director discusses student struggles as new semester begins

As a new semester begins, University Counseling Service Director Barry Schreier said the demand for mental-health care on college campuses is “bottomless.” For those struggling with mental health, UCS offers a litany of resources.

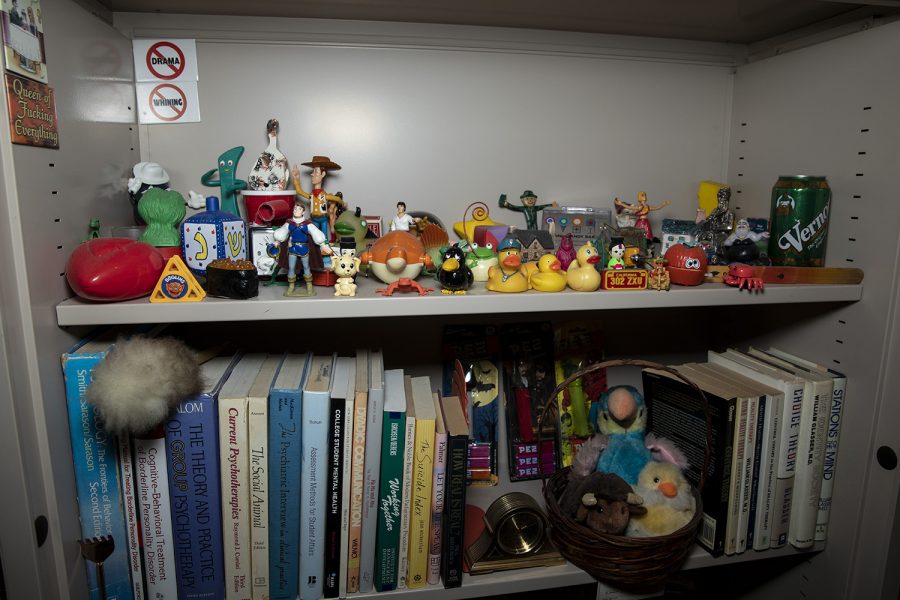

Pieces of University of Iowa Counseling Services Director Barry Schreier’s office collection are seen on December 12, 2019. Schreier recently was awarded the Association of University and College Counseling Center’s President’s Award for Meritorious Service in the National Field of Campus Mental Health.

January 21, 2020

Despite a frigid “welcome” back for University of Iowa students, the spring semester is underway. A new semester brings its own triumphs and hardships, and many students will utilize the University Counseling Service to deal with the ups and downs of college life — no one knows this better, perhaps, than UCS Director Barry Schreier.

The most recent data from the National College Health Assessment states that 17.6 percent of undergraduate UI students were diagnosed or treated for depression in 2019 — a jump of 8.3 percent from 2014. Schreier said this increase is because students are becoming more familiar with the vernacular of mental health, and pressure to alleviate the mounting cost of higher education.

“The demand for mental-health care on our campuses, at this juncture, is somewhat bottomless,” he said. “But the more nuanced view of it is telling folks to engage in help-seeking behavior. We say to ourselves, ‘Let’s do everything we can to reduce stigma,’ and in a lot of ways the stigma is not one-size-fits-all for different communities on campus.”

These communities, Schreier said, may have different attitudes toward engaging in help-seeking behavior. Students that are a part of an underrepresented community may have pressing concerns such as ensuring their safety or having representation on campus that push accessing mental-health services from the forefront of their minds, he added.

In addition to community identity, Schreier said he has noticed a sharp contrast in the way physical illnesses and mental-health concerns are discussed.

“When we talk about mental health, sometimes we don’t say, ‘I have depression,’ we say, ‘I am depression,’ ” he said. “You would never say, ‘I am cancer,’ so that is a major distinction. Part of what causes that is the difficulty of discerning who you are from a mental-health perspective as opposed to a physical illness. I think because of that, it brings up a lot more shame. I also think that college students are high achievers, which brings about a more individualistic mindset.”

RELATED: University Counseling Service offers new programs for students

To Schreier, the U.S. is a “ruggedly individualistic” society; this is not always a negative attribute, he said, recounting a lengthy list of individuals who have pioneered change. When it comes to mental health, however, the common expression that someone “lifted themselves up by the bootstraps” can be a deceivingly nonchalant way of pushing depression and anxiety to the side.

Although Schreier said every student needs time to themselves, he added that seclusion can lead to mental-health concerns such as suicidal ideations, which occur when someone thinks about, considers, or plans suicide.

“When a student is experiencing suicidal ideations, that can be one of the most lethal parts of depressive thinking. So much of that mindset can be bottled up,” he said. “Again, we have to start the conversation about engaging in help-seeking behavior, and one of the things we do at University Counseling Services where we are a national leader is in group therapy.”

These group-therapy programs, which have blossomed over the last five years, include a variety of topics important to students; this includes workshops geared toward anxiety, body image, and groups for male and female students. The formation of these groups, Schreier said, was two-fold; individual counseling can be difficult at a large scale, and a group setting helps students realize they are not alone in the problems they face.

“When students are sitting in a group setting, they can look around to others who are in the same position and say, ‘Wow, I feel a little less irrational now.’ The current research is telling us that if we ask the average college student if they feel alone, they say, ‘I do not, I have readily available connections all around me,’ ” he said. “When we ask the same students, however, if they feel lonely, the answer is often yes.”

Likening this dissonance to the difference between a house and a home, Schreier said the two terms “alone” and “lonely” sound similar but have different connotations. Group-therapy sessions, he added, can help students gain coping mechanisms for these feelings.

National data from the American Psychological Association state that 32 percent of college counseling centers reported at some point throughout the year there was a wait list for mental-health care. Schreier said he realizes the ever-growing counseling needs of the UI’s 32,000 students and added that programs such as group counseling and Let’s Talk Hawks strive to meet these demands.

RELATED: UI celebrates progress on mental health, opening of East Side counseling location

The onset of a new semester — especially amid a cantankerous political climate — can increase the stress students feel while perusing social media, Schreier said. Although platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have helped spread awareness and reduce stigma surrounding mental-health concerns, he added that “information overload” continues to be a prevalent concern among students.

“My more cynical side will say there is nothing you can do about [information overload], it’s just the nature of the society we have created for ourselves. The less cynical side of me, however, realizes that there are positive communities online and we can filter the content we see,” he said.

Regardless of the challenges related to social media, Schreier said technology has been a valuable tool in the mental-health profession. Kognito, an online suicide-prevention simulator, has already been used by nearly 6,000 people in the UI community.

Schreier joked that he graduated college “longer ago than I’d care to admit,” adding that aiding the concerns of college students is a challenging — yet rewarding — job that is never finished.

“I think we need to stay flexible,” he said. “I think our approach needs to be nuanced and we need to make sure we’re keeping our ear to the national level so that we are doing our best to stay ahead of the conversation. I never want to be a campus that wasn’t paying attention.”