The fall of the Berlin Wall through Iowans’ eyes

Three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Iowa City natives and the university alike have gathered to remember the structure, which separated Germany for the better part of 30 years.

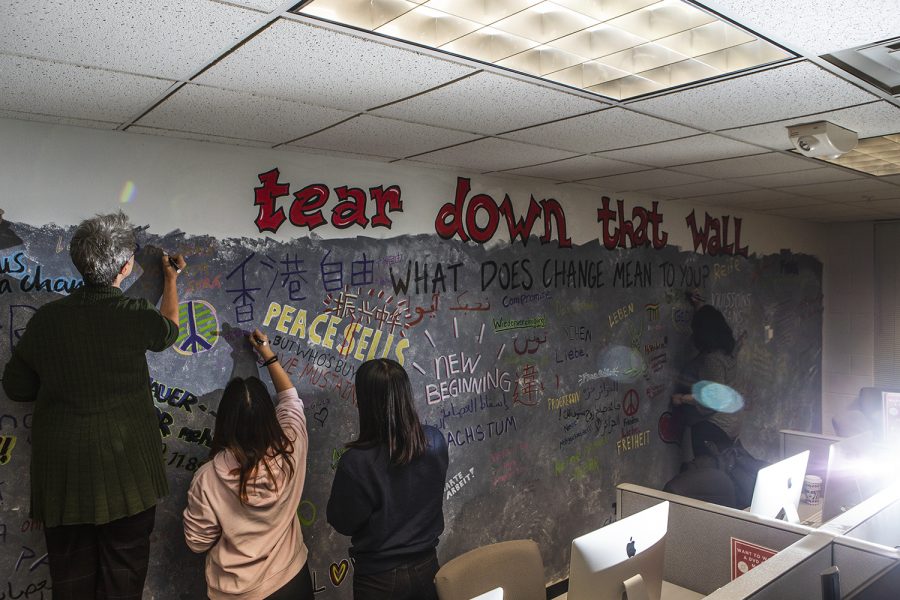

Attendees write on the Berlin Wall artwork in Phillips Hall on Thursday. Members of the community contributed to the piece by adding words regarding their feelings about the relationship between the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and President Trump’s efforts to build a wall.

November 7, 2019

Should you step into the Language Media Center in Phillips Hall this semester, you will be met with a mini replica of the Berlin Wall. In conjunction with the 30th anniversary of the wall’s demise, the University of Iowa has posed a deceivingly simple question to students, staff, and faculty: What does change mean to you?

Participants are invited to use “any language or artistic expression” to share their thoughts — inscriptions include a simple flower, while other scrawlings delve deeper into the legacy of the towering structure that separated Germany for the better part of three decades.

Ich wäre nicht hier in Iowa City ohne den Mauerfall (I would not be here if it wasn’t for the fall of the Berlin Wall), one inscription reads. In addition to the mini wall, a number of events this week discussed the ramifications of separation and the lingering effect of Mauer im Kopf, or the idea of the wall still living in the heads of Germans today.

For a brief moment in time on Wednesday afternoon, Meeting Room A of the Iowa City Public Library transformed into East Germany for a panel discussion on the wall’s legacy through the eyes of Iowa City residents who witnessed the historic events firsthand.

Iowa City City Councilor-elect Janice Weiner recalled with great detail the events that lead up to the wall’s collapse through what she called “the lens of a professional observer.” From April 1988 to June 1990, Weiner was stationed in East Berlin with the U.S. Embassy.

Of all the moments Weiner recalls from her time in Germany, she said few can compare with the night rockstar Bruce Springsteen was allowed to play in East Berlin; since the wall’s destruction, Weiner added that this night was a seminal example of people coming together, peacefully, to voice their concerns about an oppressive government.

“[The East German government] wanted to use him, but he didn’t allow himself to be used. There was a sea of probably 60,000 people who had come from all over the country,” Weiner said. “And despite what we all know about the song ‘Born in the U.S.A.,’ I still get chills when I think of him singing that song and all of a sudden seeing all of these homemade U.S. flags unfurled in the audience.”

Although it may be hard to imagine a more salient moment that defined the months leading up to the wall’s demise, Weiner also attended the now-infamous press conference where East German Spokesman Gunter Schabowski misread a press release, causing thousands of Germans to believe that the wall was to be demolished.

“Someone walked in and handed [Schabowski] a piece of paper, and once he read it we all turned to each other and said, ‘Did he just say what we think he said?’ The statement he made, in essence, told people it was OK to cross into West Berlin,” Weiner said. “I believe that the wall didn’t fall, the people pushed it down.”

German adjunct instructor Ulrike Carlson was only 9 years old when the wall fell, but shared her memories of hushed political conversations, attending demonstrations with her parents, and history textbooks laced with photos of Vladimir Lenin.

“Life was permeated with a certain amount of propaganda,” Carlson said. “… And even as a child you would watch West German television, and you would see commercials for Barbie Dolls and other toys that just didn’t exist in East German stores. So even as a child, you would realize that life was different for you — I had relatives in the United States and West Germany who would send packages with unheard-of treasures.”

Directly behind Carlson, fastened to the wall with Command strips, was a banner made from an old bedsheet reading “our schools should be schools of democracy.” Even at her young age, Carlson recalled carrying the banner through the streets with her parents. Even though these peaceful demonstrations assisted in ending the East’s oppression, Weiner added that this came at a cost to many.

“What kept things in check was the Stasi or secret police,” she said. “They had a number of unofficial collaborators who were often not recruited under duress to report on fellow citizens, sometimes fellow family members. I was often surprised to learn that people collaborated with the Stasi … someone I knew, you could have knocked me over with a feather when I found out they were involved. You just had to assume you were being listened in on.”

Even though Iowa City Mayor Jim Throgmorton did not visit Germany until after the wall fell, he said his professional interest in the structure as a city planner was piqued by its lasting impact on physical and psychological separation.

“Physical design can enable what I’m going to call the poetic narratives of ethnically homogeneous native-born residents who design poetic cities that reproduce a singular, essential notion of nation and national identity,” he said. “It also tells us that when not supported by ritually democratic processes, these public spaces can become sites of gruesome oppression and control.”