Plate of insecurity: A student’s struggle to access food

As more and more research rises to the surface surrounding food insecurity — the lack of accessibility to healthy food — one student weighs in on her experience growing up and attending a postsecondary institution food insecure.

Cathryn and her husband Dylan walk through the University of Iowa campus on Tuesday, September 10, 2019. Cathryn is a senior graduate student and her husband is an artist.

Carrying several pounds of peanut butter, milk, and minimal produce in their oversized backpacks, a young couple walks heavily from the Food Pantry at Iowa in the Iowa Memorial Union to their home one-and-a-half miles away. Without the support of the pantry, the two say they would have a much harder time to make life work in Iowa City.

Putting food on the table is a huge problem for UI graduate student Cathryn, 28, and her husband. Cathryn and Dylan deal with food insecurity — the lack of access to quality, nutritional food at an affordable price.

As a UI graduate student with a focus on agricultural literacy and being employed as a teaching assistant, Cathryn calls the Food Pantry at Iowa her lifesaver. Her salary is not even half of what she used to make when she was a full-time teacher.

From a UI Fall 2018 survey on part-time wages, the average rate of pay for a student working part-time is $11.09.

“About 80 percent of my income is bills,” Cathryn said. “I have about 20 percent left — and out of that, 20 percent I want to save. Every month, I’m left with around $100 for clothing or food — most would go to food. Now with the pantry, I can have a life outside of college.”

Without the Food Pantry at Iowa, Cathryn and her husband would not be able to enjoy simple things such as a drink with a friend.

“The pantry has been really nice, because we don’t have to worry about a food bill at all,” Cathryn said. “We get a wide range of foods — it’s not just your boxed pasta and beans. You also get your fresh vegetables and your meat, and sometimes milk, which is very exciting.”

Cathryn and her husband Dylan fill their backpacks with groceries from the food pantry in the Iowa Memorial Union on Tuesday, September 10, 2019. Cathryn is a graduate student and Dylan is an artist. Using the food pantry helps them save money on groceries so they can put money towards other expenses. Leaving the food pantry with groceries in their backpacks, they walk over a mile home.

In a food journal Cathryn wrote for a class, she said that the family of two cut cost by going vegetarian in hopes of saving money. However, thanks to the Food Pantry at Iowa, Cathryn and her husband have been able to incorporate meat into their diet again.

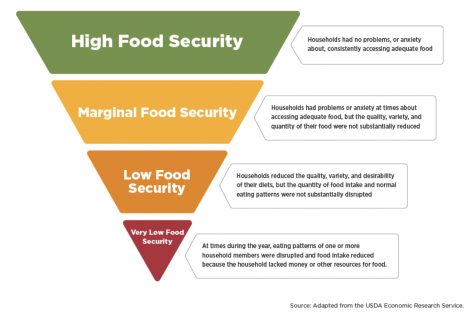

There are four levels of food insecurity, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, ranking from high insecurity to very low insecurity.

Food Pantry at Iowa Executive Director Christian Zirbes said food insecurity doesn’t present itself on the surface, and few students are aware of the issue at hand.

“People think it is OK to live off of a diet of ramen and pizza in college,” Zirbes said. “I think that people use the pizza and ramen diet as an excuse to sweep the issue of food insecurity under the rug. It shouldn’t be that way.”

In the last 12 months, Zirbes mentioned that the Food Pantry at Iowa has served just under 2,000 students.

The Food Pantry at Iowa has served students since the fall of 2016 and expanded in the spring of 2019 to the west side of the UI campus.

With an appreciation for the simple things, such as peanut butter, Cathryn has been grateful for all that the Food Pantry at Iowa has given her family.

“A lot of times you don’t know if someone is struggling or not, that’s why it’s so nice to have the pantry,” Cathryn said. “It allows us to have more freedom with our funds so we don’t have to worry about that $80 bill of groceries or having to see if we will be able to buy groceries.”

Through donations and produce from the UI Gardeners, the food pantry has remained accessible to all students who identify as food insecure.

While the pantry compensates for everything Cathryn and her husband could need in terms of food, a struggle the couple faces is making sure they can carry all that they take from the pantry. With the cost of parking and gas, they avoid using their car to make trips to campus. The two plan out their trips to the pantry with empty backpacks to make sure that they can carry all of their groceries for the week on their mile-and-a-half walk home.

Cathryn and her husband Dylan walk home from the food pantry in the Iowa Memorial Union on Tuesday, September 10, 2019. Cathryn is a senior graduate student and Dylan is an artist. Using the food pantry helps them save money on groceries so they can put money towards other expenses. Leaving the food pantry with groceries in their backpacks, they walk over a mile home.

“[We’re thinking about] not only what we need, but what can we actually carry,” Cathryn said. “When you’re carrying 15 pounds of food, it’s a lot to walk a mile and a half, especially if it is really hot or really cold.”

While most days during the school year are plentiful in terms of what the food pantry can offer, there are few days that stock remains scarce, and students are left with minimal options, sometimes lacking dairy, bread, and produce.

The Food Pantry at Iowa currently accepts donations of nonperishable items from the public 24/7. Primarily, donations come from the UI community, the UI Gardeners, and other food organizations that donate items.

“There’s certain days where the pantry might be completely empty,” Cathryn said. “So you’re like, ‘Well, I got this one pound of ground beef. How do I make that last until next week?’ ”

Cathryn and her husband only go to the pantry once per week — as per regulations of the food pantry — so on days where the pantry is scarce, they have to make do with what they have.

Katharine Broton, a UI assistant professor studying the implications of college unaffordability, said in an email to The Daily Iowan that there are no nationally representative longitudinal data on this topic.

“Most students who are basic-needs insecure work and receive financial aid, but they still report problems making ends meet,” she said in her email. “Over the past three decades, the price of college attendance has risen while financial aid has not kept pace and real family incomes have stagnated. While almost half of all undergraduates receive Pell Grants, many others have scarce resources but do not qualify for that support.”

According to a Government Accountability Office report, an increasing amount of low-income students are enrolling in college. National Postsecondary Student Aid data show the percentage of all undergraduates who had a household income at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty line increased from 28 percent in 1996 to 39 percent in 2016.

Upon completion of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, a student may qualify for a Pell Grant based upon financial need, the U.S. Education Department’s website states. These grants, awarded to students with the highest financial need, do not need to be repaid and are not guaranteed to students.

Broton also mentioned that other students are disadvantaged by the federal-needs analysis, which allocates financial aid based on their parents’ financial resources, even though many students cannot access those resources.

“While awareness of the problem [of food insecurity] has increased over the past five years and certain institutions have made great strides, far too many students are attending college without first meeting their basic needs,” she said in her email.

Currently, the University of Northern Iowa has a “Panther Pantry” available to students with hours similar to the UI’s. Iowa State University also has “The Shop” available for their students experiencing food insecurity. Both are relatively new to their campuses.

Being food insecure is not new to Cathryn; rather, she’s dealt with the problem all of her life.

A Tipton, Iowa, native, Cathryn came from a single-parent family, alongside her two older brothers. According to the Feeding America website, poverty and food insecurity are closely related. Wages and other household expenses can determine whether one is food insecure.

While Cathryn said she doesn’t believe her family ever went hungry, she was aware they relied on food pantries growing up.

The USDA distinguishes between the terms “food insecurity” and “hunger” as the following: food insecurity is a social condition of limited or uncertain access to healthy food, and hunger is an individual-level condition that may result from food insecurity.

“When you are a kid, you don’t know what poor is,” Cathryn said. “It came around third or fourth grade when I started noticing those clothing differences.”

Around the holidays, banks or other businesses placed stars with needy children’s names and gift wishes on Christmas trees for the season, Cathryn said. Her fourth-grade class had received a star one day from one of these businesses.

“It was my brother’s star,” Cathryn said. “I knew it because he asked for a fishing pole and the exact brand name of the pole. When I told one of my classmates, their response was, ‘Oh no, those things — those things are only for people that are poor.”

With tear-filled eyes, young Cathryn came home a wreck.

“[That’s when] I knew that we were poor,” Cathryn said.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey of 2017, the poverty rate in Iowa City is 28 percent.

“Having a single parent who is struggling to put food on the table puts it in perspective for you — so I became a teacher,” Cathryn said.

Taking her own childhood into account, Cathryn watched students who wore the same clothes every day and came from homes like her own — trying to do the best she could for their situations.

As a first-generation college student transitioning to Augustana College for her undergraduate years, Cathryn tried to readjust to a life on her own away from her family.

From watching her mother struggle to support their family, Cathryn used this factor to motivate herself to defy the odds she faced.

The Government Accountability Office reports that having a low income is a consistent factor for food insecurity. The other factors include: being a first-generation college student, being homeless or at risk of homelessness, and more.

Although there were meal plans and other options available, there were no food pantries available for undergraduate students at Augustana, Cathryn said.

Cathryn and her husband Dylan pick up food from the food pantry in the Iowa Memorial Union on Tuesday, September 10, 2019. Cathryn is a senior graduate student and Dylan is an artist. Using the food pantry helps them save money on groceries so they can put money towards other expenses.

Until recent years, college food pantries were not around for students to access. The first official student-run food pantry began at Michigan State University in the mid-1990s. Since then, peer institutions have taken it upon themselves to expand on the model that Michigan State set forth.

From a life filled with struggle and perseverance, Cathryn has found a passion to pursue as a career.

“One of my passions is to — maybe someday — as a nonprofit, is to do some sort of food pantry in a food-insecure area that also matches with STEM education — so like an after-school program with a food pantry as well,” Cathryn said.

Through a life of struggle, Cathryn is left hoping that someday she can create a change that will benefit the lives of others.

“I think a lot of people think of food insecurity as people starving,” Cathryn said. “It’s not really that — it’s people that are just struggling.”