Lawmakers at a crossroads on criminal justice

With more than 8,500 people incarcerated in Iowa, state legislators are looking back at change to the criminal-justice system this year.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds speaks during her first Condition of the State address in the Iowa State Capitol in Des Moines on Jan. 9, 2018.

With a steadily rising prison population and recidivism rate in Iowa, Democrats and Republicans in the Iowa Statehouse are at a crossroads over whether criminal-justice reform was adequately addressed during the 2019 legislative session.

Some bills on criminal-justice reform didn’t make it through the state Legislature during this session, which ended April 27, including a bill protecting people from criminal defense in the case of self-defense and another that would eliminate a question asking about someone’s criminal record on a job application. One prominent example is Gov. Kim Reynolds’ proposal to add an amendment to the Iowa Constitution allowing some felons to vote after completing their sentences.

A criminal-justice omnibus package passed this session with nearly unanimous bipartisan votes. That package includes measures that expunge some crimes from a person’s record and reduce sentences for Class B felonies. The bill also allows judges to oppose mandatory minimum sentences.

In Iowa, there are 8,545 people serving prison sentences, and 49 percent of that population is incarcerated for violent crimes, according to the Iowa Department of Corrections. The number is steadily increasing. As of 2018, there were 400 more incarcerated people than in 2013 — though Iowa’s 2018 prison population was less than the high point, 8,800, in 2011.

The recidivism rate, or rate at which people return to prison, has been rising as well. In fiscal 2017, the recidivism rate was 35.4 percent, which rose to 37.8 percent in fiscal 2018.

University of Iowa political-science Associate Professor Timothy Hagle, a deputy director and chief of staff in the Office for Victims of Crime in 2005-06, said Republicans and Democrats can often agree that there needs to be some kind of change to the criminal-justice system, but they disagree on how to approach it.

“You always have to be careful throwing out one term [criminal-justice reform], but a lot of times, that’s what politicians do,” Hagle said. “They latch onto some phrase and say, ‘criminal-justice reform.’ OK, but what is it exactly that you want to reform?”

House File 472, or the “Ban the Box” bill, was one criminal-justice reform bill that did not make it through the Legislature. The bipartisan bill, introduced Feb. 26, would have prohibited public employers from asking potential employees about criminal histories on job applications.

The “box” refers to a question that would require a person to indicate if the person had a felony conviction on a job application. The measure would not have applied to private employers.

Rep. Mary Mascher, D-Iowa City, who cosponsored the bill when it was introduced in the House, pinned the lack of Republican support for the bill failing to pass this session.

“Many [Republicans] feel they need to keep punishing people,” Mascher said. “We shouldn’t keep putting barriers up for people once they’ve served their time.”

Senate File 407, sponsored by Sen. Zach Wahls, D-Coralville, and Claire Celsi, D-Des Moines, offered restrictions on criminal defense in cases of self-defense or provocation. Wahls said in an email to The Daily Iowan that the bill was not rolled into a larger omnibus package after a procedural ruling by the Senate president prevented it from being tacked on.

One key priority for Reynolds — restoring some felons’ voting rights through an amendment to the state Constitution — did not advance this session, either.

RELATED: Reynolds proposes restoring voting rights to convicted felons in Condition of the State

Hagle said that specifically with the proposal of restoring felons’ voting rights, there are historical disagreements between Republicans and Democrats on what constitutes its being not only criminal-justice reform but also a human-rights issue.

“The idea of restoring voting rights for felons is one in particular that you get a few people on the Republican side who are in favor of it, but by and large, it’s not something [Republicans] are keen on,” Hagle said.

In 2005, then-Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack, a Democrat, signed an executive order that restored voting rights to felons who completed their sentences. In 2011, then-Gov. Terry Branstad, a Republican, rescinded that order when he took office.

Reynolds’ measure, despite receiving unanimous support in the Iowa House, ran into a bottleneck in the Senate after Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Sen. Brad Zaun, R-Urbandale, decided not to bring the bill up in committee. Zaun did not respond to requests for comment.

Some Democrats, such as Mascher, think Reynolds should have issued an executive order while the constitutional amendment moved through the pipeline.

RELATED: Iowa’s road to restoring the right to vote to felons

Reynolds said in a statement emailed through a spokesperson to the DI that she would push for restoring voting rights next session.

“While the votes fell short in the Legislature, I remain committed to getting this done,” she said.

Rep. Mary Wolfe, D-Clinton, said some state lawmakers on both sides of the aisle may be hesitant to push reforming criminal sentences for such crimes as robbery because a future opponent could amplify fears of more criminals on the streets in future elections.

“Certainly there are people in my caucus who are like, ‘No one cares about criminal-justice reform,’ ” Wolfe said. “We’re not going to win any election by saying we voted to reduce mandatory minimums, so let’s not do that, let’s not go there, that’s not a good road for us. I think they also understand that what we are doing isn’t working because … we have more people in prison than we’ve ever had.”

Rep. Bobby Kaufmann, R-Wilton, member of the Iowa House Judiciary Committee, said he does not see the political implications brought up by Wolfe for Republicans who support criminal-justice reforms such as reducing mandatory minimums.

“Criminal-justice reform passed [this session] — none of those assumptions apply,” Kaufmann said, referring to the omnibus package.

Wolfe said that while she doesn’t think there was an adequate push for criminal-justice reform at the state level this session, it’s only a matter of time before more substantive reforms addressing mandatory minimums can pass the Legislature.

“[Iowa] should be spending more money on rehabilitation and re-entry and less money on the actual incarceration,” she said. “That’s an investment. It’s hard to make investments. It’s easier to just to vote for stuff that locks people up longer.”

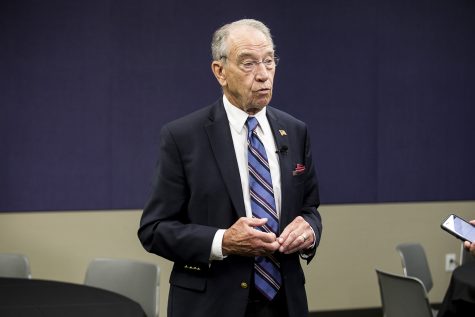

Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, talks to reporters at the Eight Circuit Judicial Conference in Des Moines Friday, August 17, 2018. During his remarks, Grassley told reporters hearings for Trump’s U.S. Supreme Court Nominee, Brett Kavanaugh would begin Sept. 4, after the committee finishes reviewing nearly 1 milllion documents pertaining tho Kavanaugh’s nomination.

The general fund for Iowa prisons for fiscal 2019 is $381.78 million.

Sen. Zach Nunn, R-Altoona, a member of the Iowa Senate Judiciary Committee, said he would counter the notion that there wasn’t a push for criminal-justice reform this session, pointing to the omnibus package that received bipartisan support in the Iowa House and Senate and garnered unanimous votes in both chambers.

“I think it’s very clear that you can be tough on crime but also smart on crime in a meaningful way,” Nunn said.

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, spearheaded a sentencing-reform bill in the U.S. Senate that received nearly unanimous support in the House and Senate in December and was signed into law by President Trump in February. The bill, known as the First Step Act, was endorsed by the American Civil Liberties Union and a long list of other national organizations.

While the omnibus package on the state level had bipartisan votes, it did not include some measures highlighted in the First Step Act that Democrats had hoped would pass. Those measures include employment-assistance programs once prisoners are released and reducing mandatory minimums for young offenders who committed violent crimes.

Kaufmann said the definition of a “push” in the Legislature is when a bill is passed.

“[The omnibus package] would not have been as noteworthy as the federal bill, but I think we took a great first step,” Kaufmann said.