Baseball, free verse, and the ‘inventor’ of gay identity: Whitman at 200

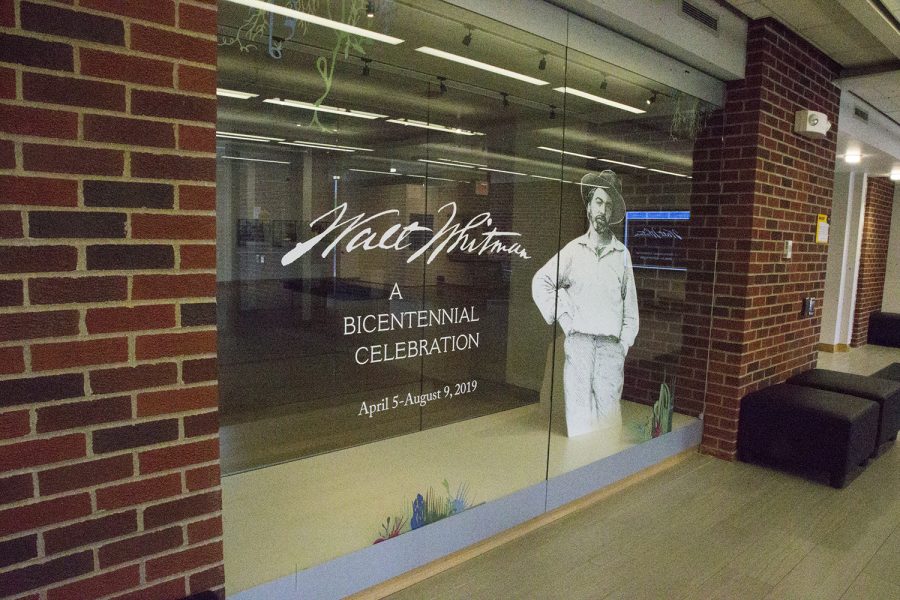

On April 5, The UI Main Library Gallery opened a special exhibit celebrating Walt Whitman’s 200th birthday.

Select pieces from the exhibit honoring the 200th birthday of author Walter Whitman at the University of Iowa Main Library on April 9.

April 11, 2019

University of Iowa Professor Ed Folsom wants students to take a second look when entering or exiting the north entrance of the Main Library for the next few months.

‘‘That place you walk by all the time — actually stop,’’ he said. ‘‘Take advantage of this opportunity. There are very few university libraries that have a gallery space like this.’’

On April 5, The Main Library Gallery opened a special exhibit celebrating Walt Whitman’s 200th birthday. The exhibit draws from UI Special Collections’ extensive Whitman archive as well as personal collections to present a material narrative of his career, ranging from early journalism to popular fiction to accounts of his volunteer work in Civil War hospitals and his later, more celebrated poetry. It will occupy the gallery through Aug. 9.

“Inevitably, in some point in every American poet’s career, they have to come to grips with Walt Whitman,” Folsom said. “Poets around the world have continued to talk back to Whitman … because his poetry always treated the ‘you,’ the reader, as somebody who had to respond.

“[They’re] saying, ‘Well, the America you promised, it’s never materialized, we’re still as far from that ideal as you were. Here we are, 200 years after you were born, and we still have vast inequities in wealth distribution, we still have racism, we still have attacks on people for being gay. Where is the American you promised?”

Folsom said historians look to Whitman as the “inventor” of gay identity.

“Before Whitman, there were what we would now call homosexual acts, but there was not such a thing as a gay identity, and Whitman gave voice to a gay identity — that is, what men loving men would sound like, he gave a vocabulary to it,” he said.

Folsom has been the editor of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review for 36 years and is the codirector of the ever-expanding, open-access Walt Whitman Archive. He is a curator of the bicentennial exhibit, along with Stephanie M. Blalock, an associate editor of the Archive and a digital humanities librarian, and Brandon James O’Neil, a UI Ph.D. candidate in English.

The exhibit looks at the famous sides of Whitman — revolutionary democrat, free-verse avant-gardist, literary celebrity, writer of homoerotic poetry — as well as the aspects of his life and career that visitors might be unfamiliar with: journalist, sensational novelist, bookmaker, self-promoter, apologist for baseball and photography.

Folsom said that for Whitman, “the idea of photographic beauty taught us a whole new way of thinking about beauty as fullness, completeness.” It inspired the politics and formal experiments of his poetry, asking the question, “Can I create a poem where the page is as open to American experience as the photographic plate is open to whatever the sun illuminates?”

Six of the world’s leading Whitman scholars will visit the exhibit during its run, starting on April 12 at 3:30 p.m. with Betsy Erkkila, the author of the forthcoming The Whitman Revolution: Why Poetry Matters.

“Two hundred years after his birth, it’s as if he’s still producing work,” Folsom said. “You know, we have a new novel, a new journalistic series … that are now published, and being studied, and incorporated into what we had already known about Whitman … I’ve talked to so many students who tell me reading Whitman the first time just changed their lives.”

Curator O’Neil had that kind of experience.

‘‘When I was about 14 or 15 years old … I grew up in a very conservative household, and I had all sorts of feelings that I didn’t have quite have language for,” he said. “Somehow, I got my hands on a copy of Leaves of Grass, and in Whitman’s poetry I found language for some of the feelings that I had … This exhibit, for me, is an opportunity to share that language with other people who might be looking for it.”

The exhibit features many original editions of Leaves of Grass, Whitman works in translation, Iowa documents connected to the poet, and things written on or touched by Whitman’s own hand.

Some hidden gems the curators hope visitors will enjoy include the “first-ever book-cover blurb” on the 1856 edition of Leaves of Grass, a cast of Whitman’s hand, a miniature Japanese translation of the poem ‘‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’’ that can be worn as a necklace, and his then-bestselling story, ‘‘Death in the School-Room,’’ published in a prestigious literary journal when Whitman was in his early 20s.

Despite its vast scope, this exhibit only scratches the surface of Iowa’s “amazing” collection of Whitman material.

There are also two interactive maps available on the touchscreen outside the gallery: one tracing Whitman’s sent and received letters and one tracing reprints of Whitman’s fiction in newspapers and magazines from 1841 to present.

‘‘Which way does your beard point tonight?’’ Allen Ginsberg asked an apparition of Walt Whitman in 1955. For the next few months, you may find an answer at the library gallery, discovering and rediscovering one of America’s greatest artists.