‘Black Klansman’ Ron Stallworth remembers his time in the KKK

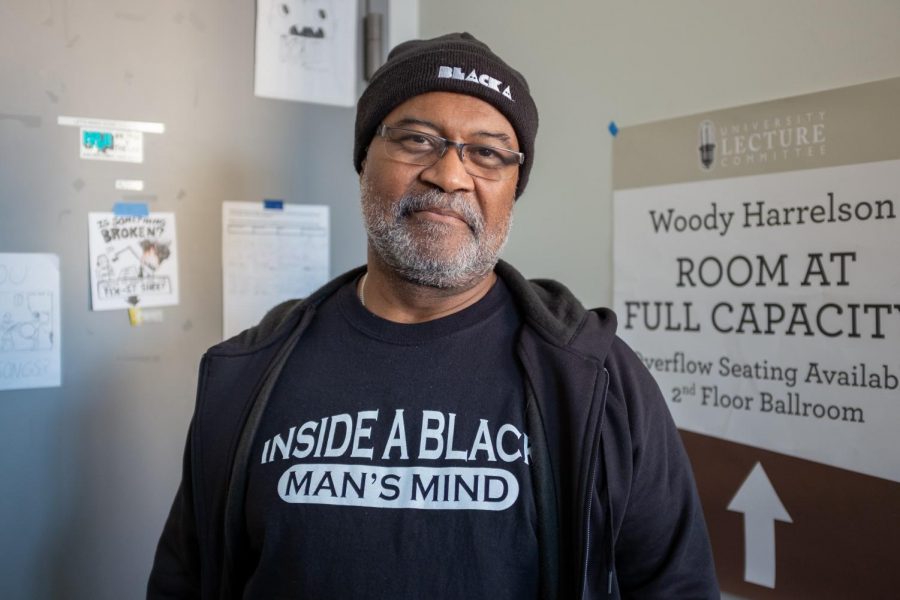

Ron Stallworth poses for a portrait on Wednesday, January 23. Stallworth, whose memoir “Black Klansman” was adapted into a Spike Lee film, discusses his time as a police officer and his infiltration into the Ku Klux Klan.

January 23, 2019

“If you play their game, you can defeat them at their own game.”

As Ron Stallworth sat behind a microphone in KRUI’s studio Wednesday afternoon, the crisp January sunlight seemed to shine through him, creating a fairytale-like halo around his face. He was clad in all black, including a beanie he later told me was a Christmas gift from Spike Lee. Throughout the interview, his wife Patsy sat by his side.

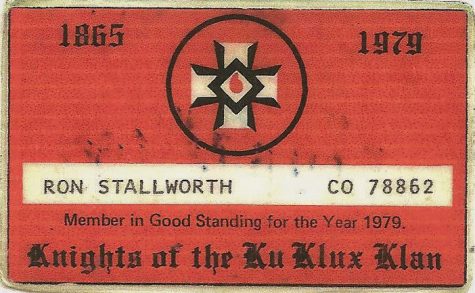

In some respects, Stallworth’s story is stranger than fiction – he became the first black detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department and infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1970s.

The film BlacKkKlansman, which was directed by Lee and released last year – 40 years after Stallworth’s undercover operation – is nominated for six Academy Awards and chronicles the bizarre, historic investigation into the KKK and its former Grand Wizard David Duke.

Although Stallworth laughed as he described the surreal nature of seeing his story on the big screen, his demeanor quickly changed as he discussed the climate surrounding nationalism in the 21st century.

“America is in a scary place today because people want to hear [alt-right rhetoric] — they want to believe it,” he said. “We’re going to get out of it, but I don’t know how soon we will and how much damage will be done until we get out of it.”

During the investigation, Stallworth said he had many conversations with Duke over the phone, and found it hard to contain his laughter.

“I was cracking up laughing,” he said. “You have to remember, I was working undercover, and we were pulling a con job on the Grand Wizard — you had to communicate like them to be them, or for them to believe you were one of them. It was very easy to throw those words [such as racial slurs] out because I heard those words growing up. It was very easy to regurgitate those words.”

Despite “hurling” racial slurs back and forth with the leader of the KKK, Stallworth said he always kept in mind that he was undercover, and he wasn’t actually like the people he was trying to emulate over the phone.

At times, however, Stallworth said he found it difficult to grapple with his black identity while also serving as a member of the police force.

“I was a young black cop, but when I took that badge and uniform off, I was just a black man in America,” he said. “I was subject to the same treatment as any other black person was who was not on the other side of the law…that’s something that people tend to forget.”

Today, Stallworth said a problem facing black police officers is that they are “too black for the white community, but too blue for the black community.” Police brutality, he added, can make the dynamic between police officers and the rest of the community even more strenuous.

“I was a black man, and I still am,” he said.

Although racial tensions were high in the 1970s, Stallworth said not much has changed — BlacKkKlansman, in fact, premiered at the Cannes film festival one year after the riots in Charlottesville, and the film ends with juxtaposed images of hate crimes past and present.

“We have a con man in Washington right now who has shut the government down,” he said. “The Donald Trumps of the world, the Steve Kings of the world, they’re a dying breed; even though it may not seem like it right now, we’re not going back to those times when black people had to be subservient to white people.”