A Gaythering: Safety and comfort in identity

While the LGBTQ community has made strides in recent years towards equal rights, many queer spaces remain largely underground.

Haus of Eden performer Mx. Divine poses for a portrait at Studio 13 on Wednesday, August 29, 2018.

November 7, 2018

Trying to dodge puddles, patrons flock down the alley near Linn Street, attracted by the bass and screaming adulation from a drag-lauding crowd.

The closer they come, the greater their excitement grows. After a nominal fee the world is theirs, to paint as they will. The essence of the rainbow is palpable in the flashy lighting, smiling faces, and the latest Ariana Grande song. Around every corner is an understanding individual, sharing the experience of freedom and joy. Relief floods patrons in this space, leaving the outside world behind. Here in the darkness is a sense of safety, community, and Pride.

Those in the LBGTQIA+ community face a historical and haunting fear of discrimination when heading out for a generic night on the town. Violence toward the queer community may seem largely like a thing of the past, but slurs and stares can seem just as damaging.

According to the FBI, in 2016, there were 1,255 victims of hate crimes stemming from their sexual orientation, and 131 victims targeted for their gender identity. 2018 marks two decades since the murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay University of Wyoming student who had been baited away from a bar by two men. They proceeded to rob and beat him and tied him to a fence in the cold, leaving him to die.

The Advocate, an LGBTQIA+ magazine, named Iowa City the “third-gayest” city in the U.S. in 2009, after Iowa became the third state in the country to legalize same-sex marriage. But even here, queer students and community members face judgment. Craving an outlet to let loose, queer individuals often feel unable to fully let go for fear of retaliation from non-allies. But there is an exception to this ominous trend: the vibrancy of unashamed queer nightlife in LGBTQIA+-dominated spaces.

A haven for queer individuals is Studio 13, a gay bar at 13 S. Linn St. One of the few truly safe spaces for the queer community in Iowa City, Studio 13 allows for a broad spectrum of identity, as well as a hell of a lot of fun.

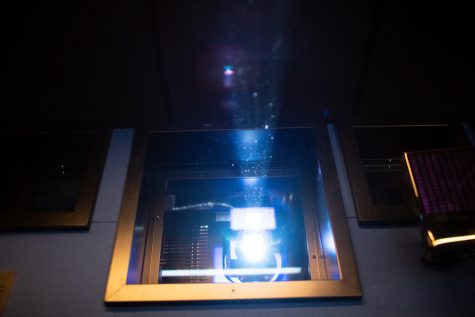

Opened in 2000, Studio 13 was originally named “The Alley Cat” but was soon changed to mimic the iconic former nightclub Studio 54 in Manhattan. The venue features two bars, a cutout wall with neon rainbow lighting, a DJ, and a stage for drag-queen performances or dancing. Patrons may sit at free tables, in VIP, or stand wherever there’s a good spot to slip a dollar to a queen.

Since 2011, the bar has been owned by Jason Zeman, who has worked to ensure the integration of queer culture into Iowa City.

“During my time as the owner, I’ve had a good relationship with many of the bars, bar owners, and the community,” Zeman said in an email to The Daily Iowan. “We collaborate with several other bars, including Micky’s, Deadwood, Sanctuary, and Shakespeare’s … on events for the [queer] community.”

Studio 13 stands as one of the only nightclubs that allows ages 19+ in the area, allowing queer people to experience queer culture through routine drag shows, dance parties, and karaoke. While allowing younger patrons grows a risk of underage drinking, the benefit of exposing younger members of the queer community to an authentic cultural experience was worth it for Zeman. After he lobbied the city, it expanded its entertainment-exemption to include LGBTQIA+ entertainment.

“I was getting several messages each month asking about drag shows for those under 21, and about nightlife, and a safe space for LGBTQIA+ persons in college but not yet 21,” Zeman said. “For many people, college is their first chance to branch out and experience who they truly are … having a place that offers a welcoming and safe environment with entertainment and people they can identify with can be life-changing.”

Zeman recently purchased local live-music venue Yacht Club, which is attached to Studio through a shared underground space. That establishment will continue to be a music venue but will undergo renovations in seating, liquor selection, sound system, staging, and kitchen. Zeman said wristbands received at either venue will provide access to both. A grand reopening will take place in the spring after most renovations are complete.

Related: Pride Perspectives: From Stonewall Riots to city-wide festivals

Zeman also owns City Liquor on South Gilbert Street.

Studio 13 has become a part of downtown nightlife, although it is not built directly on the Pedestrian Mall. The alley location creates a more secluded area in which queer patrons are not made to feel less than. When Studio 13 opened, the gay experience was much different, causing many gay bars to be hidden, Zeman said. Now, the location allows Studio 13 to thrive away from judgment and harassment it might be subjected to on the Ped Mall.

Studio 13 is a fantastic nightclub and dance bar, and it serves as a more urban-club experience. In rural Iowa, this vibe is not always everyone’s scene. Another vein of the college nightlife experience includes the house party, replete with red solo cups. Queer individuals seeking a more private, house experience may not enjoy downtown but still may not feel safe in their expression at the typical frat party.

Beginning in 2016 with a Halloween party, UI senior Aimee Fredericksen and her roommates decided to create a space in which queer people can spend time safely without having to go to a club. It’s a kiki (not the Drake kind) that meets a kegger. They called it the Gaythering.

Most Gaytherings have a holiday theme, only happening two or three times per year, Fredericksen said. Space is an issue, and they can’t have an attendance like that of Studio 13; it’s just not possible.

Their house has a bar in the basement and ample room for dancing or mingling. Fredericksen’s roommates are either queer persons or allies, and the invitations are doled out to friends by word of mouth, allowing for an intimate vibe. Friends are allowed to bring friends (who bring friends), and that’s when the magic happens.

“It’s nice to be able to go out and just hang out somewhere,” Fredericksen said. “This is a safe space; you don’t have to worry about the safety of allies and queer people. Any discrimination is not tolerated.”

Fredericksen has had minor issues at past Gaytherings, with racist costume choices or assumptions being made about the queer community, but nothing major has arisen. There is still an element of danger in holding a queer-populated party, as some attendees show up with minimal knowledge about the queer community aside from stereotypes.

“People come to a gay-dominated party and wonder, ‘Where’s the gay sh*t?’ ” Fredericksen said. “It’s not a three-hour Pride Fest in our house. I’ve had people ask where the drag queens are or use the ‘F’ slur.”

Straight voyeurism or simply occupation in spaces created for queer people can be bothersome but also beneficial. To Fredericksen, there is a possibility of predatory or judgmental eyes everywhere, but calling it out when she sees it is her top priority in keeping the Gaytherings a fun, safe space for all attendees.

Studio 13 also abides by this principle. However, most people who come to the Gaytherings understand how to act appropriately in a queer space, whether they identify as queer or not.

People are welcome to attend a Gaythering, so long as they are respectful and don’t give in to stereotypical assumptions about the queer community, Fredericksen said.

“It’s not like everyone shows up and talks about how gay they are … it’s still just a party,” Fredericksen said.

For queer people in the Midwest, queer-dominated spaces are seldom and may come as a shock to queer and straight people alike. Spaces for queer people outside of places such as Studio 13 are often hard to find, but their existence is important for those exploring their identity.

Fredericksen noted that her high-school experience in Denison, Iowa, included being called slurs simply for her undercut hairstyle. Queer-accepting or -dominated spaces seemed like insanity to her, coming from rural Iowa.

Fredericksen’s parties are not crazy keggers but are still places to let loose. The Gaytherings may end when Fredericksen graduates, but she hopes somebody takes them up in order for a legacy to be born.

While the Gaytherings are not often or disruptive, there is still anxiety from hosts and attendees of hyper-attention from police, though not for public disturbance, as historically, laws and law enforcement around the nation have shown prejudice against queer individuals solely for their identity expression.

Iowa City is largely progressive, but targeting and profiling on the basis of sexuality can still be a fear for queer individuals, whether it comes from law enforcement or the straight majority.

University of Iowa archivist David McCartney has done research on how state law has changed from the past in regards to the LGBTQIA+ community. Charges could be brought against “sexual perverts” (the legal definition of homosexuals in the late-70s), sometimes resulting in up to 10 years in prison. Offenses were generally involved with broadly defined frames of chastity, morality, and decency.

“I was interested in knowing about the background of the law in Iowa and how it pertains to queer people,” McCartney said to students at the UI LGBTQ Resource Center. “It is not a pleasant subject; in fact, the reality in Iowa is no different from practically every other state in the union.”

Since the Stonewall riots of 1969, in which gay-rights activists revolted against prejudice by law enforcement, LGBTQIA+ Pride has recurred each June around the U.S. and the world. In the corridor, the city and the Iowa City police do their utmost to maintain good relationships with the queer community, including Zeman and Studio 13, through its LGBTQIA+ liaisons.

“I feel we have a good relationship with both the city and local law enforcement,” Zeman said. “…The police interactions we do have tend to focus on making sure there are no issues and people are safe.”

The police created their LGBTQIA+ liaisons in 2014 in an effort to better their relationship with the queer community. The goals set by the police primarily are to serve productively in relations with the queer community when it comes to crime, victimization, education and involvement, and police training. Community liaisons include Officers Rob Cash and Bob Hartman.

Queer individuals continue to desire safe spaces to enjoy the same services and nightlife that their straight counterparts enjoy without reproach. Studio 13 remains a place for free queer expression. Aside from these spaces, it’s up to the community of Iowa City and the UI to embrace the queer community without prejudice, allowing for greater fun and diversity in Iowa City nightlife.