Johnson County residents can now text 911 instead of calling from most main phone carriers, though officials say calling is still the preferred option.

The service, which started Nov. 14, is primarily for the deaf and hard of hearing community as well as for situations in which calling 911 and using one’s voice could jeopardize a person’s safety.

For Tim Sheets, a deaf lecturer in the University of Iowa’s American Sign Language Program, the service would mean a more convenient method for him to call 911.

He said he can use a videophone service to call 911, but he can’t take it everywhere with him.

“If I’m at home, I can use the videophone, but if I’m out and about, being able to text 911 is great,” Sheets said through an interpreter.

Sheets said another option he has in the case of an emergency is having a friend or family member call 911 for him, but texting 911 himself would cut down the relay time.

“I haven’t had the opportunity to use it yet, but I’m sure it works great,” Sheets said and chuckled.

Tom Jones, the Johnson County Joint Emergency Communications Center executive director, said the center hasn’t received any texts in the month it has been activated, but he said the service should be reserved for people who need it.

“The main purpose behind the Text-to-911 is twofold: One is for deaf and hard of hearing, so that is a very small minority number of our calls we receive,” Jones said. “We think it’s because the people who would benefit from the Text-to-911 haven’t experienced any emergencies.”

In an announcement from Gov. Kim Reynolds in October, she said all Iowa counties would make Text-to-911 an available service for six of the most used carriers: AT&T, iWireless, Sprint, U.S. Cellular, T-Mobile, and Verizon.

Jones said Johnson County supports all but T-Mobile.

As of Dec. 5, he said, four counties in Iowa did not have at least one carrier supporting Text-to-911 services.

He stressed that people in emergencies should still call if possible because Text-to-911 has more limitations than a phone call. Those limitations include delay of relay time and the inability for dispatchers to tell a location.

“Call if you can, text if you can’t,” Jones said.

It can also take up to 30 seconds for the message to go through to the emergency dispatchers, he said, and dispatchers can’t pinpoint a person’s location without the person including it in the message.

He also warned the Text-to-911 service would not work if the message was sent in a group text or from a phone not activated on a data plan.

“If it doesn’t work, the phone will send a bounce-back message letting you know if it didn’t go through,” Jones said.

He also warned not to test the service, because it would be treated as an emergency call.

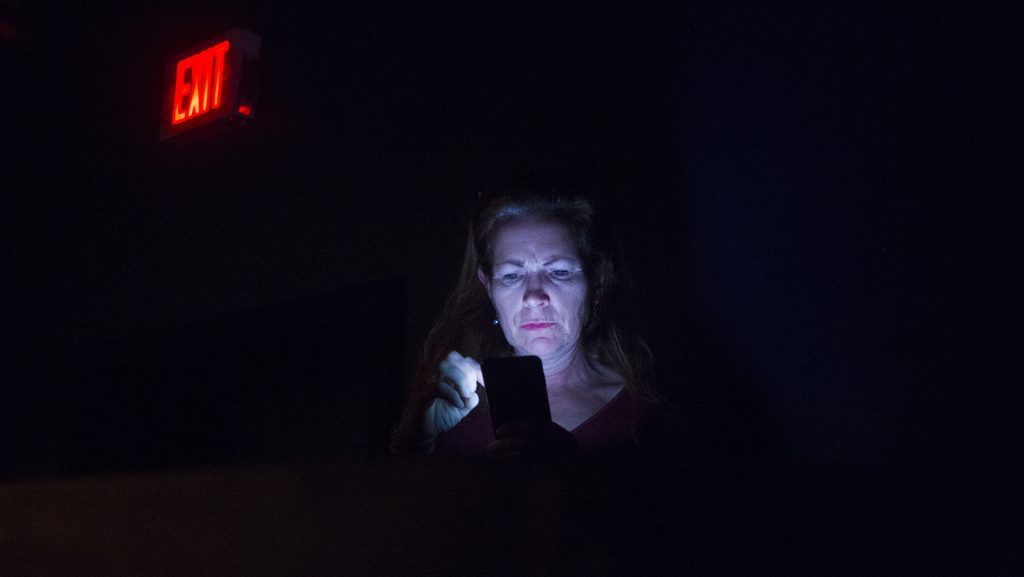

In addition to the deaf and hard of hearing community, the service also can be used in a situation where it’s in the person’s best safety interests to make the call for help discreetly, such as in cases of home break-in or domestic assault.