By Levi Wright

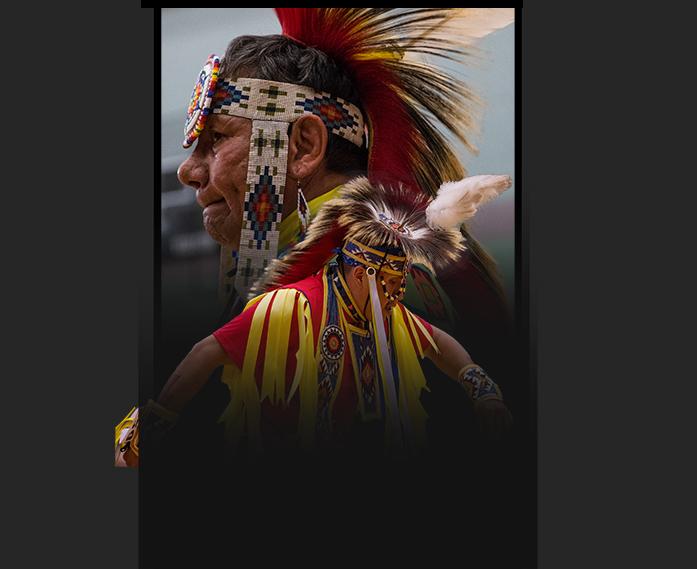

On Saturday, the Field House will host the University of Iowa’s 23rd Powwow, organized in collaboration with the UI Native American Student Association. The dynamic event, a series of performances delivered over the course of the day, gives Native Americans a chance to celebrate and honor their varying, vibrant cultures. Participants from all across the country will be in attendance to perform some of their ancestral dances and songs, act as one of the event’s many vendors, or merely attend to soak up the culture.

“We come into this arena, this circle, to celebrate life, and that’s exactly what we do with singing and dancing,” said Wayne Silas Jr., the arena director and a member of the Menominee and Oneida Nations of Wisconsin. “We go, and we meet up with relatives and close friends that we know very well, because of these gatherings. We share photos, we share good times, we share food together, and we make memories. When the festivities are over, we go back to our homes and anticipate the next one.”

The first songs to kick off the event will be the “Grand Entry” and the “Flag Song,” both ceremonial songs that function as ways of showing patriotism and valor for one’s tribe. The “Grand Entry” can be a way of bringing together all the different tribes in attendance for the spectacular event, and the “Flag Song” is a way to pay respects to the many flags that will gather in the Field House.

“We have songs for all kinds of different things. There are certain family honor songs that belong to certain families, there are songs to honor our warriors and veterans, there are songs that we sing socially while dancing and having a good time, there are songs by men dancers, women dancers, there are songs about healing; it goes on and on,” Silas said.

The events are ways not only to observe Native American culture, but to engage with it as well, at least to a small degree. This experience doesn’t come without countless hours of labor, however, which, in this case, was largely provided by members of the university’s Native American Students Association.

“[The association provides a place] where you can come and feel inclusive, you can come get a meal, you can come talk to other students who identify as Native American or have a history of indigenous background,” said Monica Herrera, the vice president of finance for the organization. “I feel like that’s an important environment to be in.”

The Powwow also doubles as a chance for the association to be heard and for it to show their culture to others. Native Americans have faced much marginalization even recently; the government has reapproved construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which is set to cut through what Native Americans consider to be sacred land. Now more than ever, an event to showcase Native American culture is needed.

“[The Native Association] is really important on campus for students, because it’s a place where we get to come together and mostly socialize as well as talk about indigenous issues and advocate for those kinds of things on campus,” organization President Jessica Owens said.

Every aspect of the Powwow represents some form of Native American culture, from the clothing to the songs and dances the members perform. Together, for Native peoples, these disparate pieces come together to form an overarching sense of self.

“It is an identity. I’ve been singing and dancing for as long as I can remember,” Silas said. “It was just a way of life, and it’s the same for my children now. I think what it does is it keeps me connected to who I am, not only as a human being, but as a Native American. It keeps me connected to generations before me, my parents, my grandparents, and my ancestors.”

The Powwow not only preserves these cultural arts, it also serves as a way to continue expanding and reinterpreting those traditions with each passing year. For some, the Powwow is a way to keep children off the streets, and set them on a positive path for the rest of their life. It can act as a great way of developing role models for children to look up to and one day become.

“You get to remember your cultural identity and celebrate that,” Owens said. “A lot of us have grown up going to Powwow, so it’s a very comfortable space for us to be in, as well as to be able to share in the community around us.”

The Powwow isn’t exclusive to Native Americans. It’s open to anyone who wants to learn and experience a new culture.

“A majority of non-Native Americans’ knowledge [about Native peoples] comes from Hollywood, and so they already have a stereotype to what they think Native Americans are,” Silas said. “Those who attend, they want to know more, they want to see more, or they want to do something really outstanding with friends or their family, and they go see what it’s about. I guarantee you, everybody will walk away with good feelings, good teachings, something new, and they’ll make new friends.”