Pediatric brain cancer has a higher mortality rate than other forms of cancers, and that spurs pediatric oncologists at University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics to find more innovative treatments.

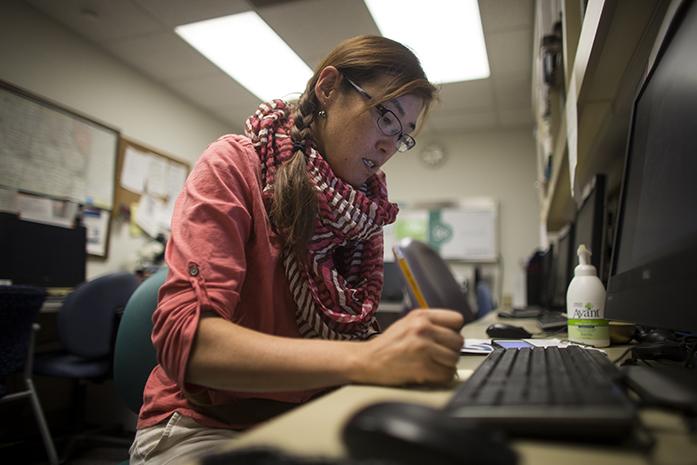

“Looking at data, pediatric brain cancer has a 70 percent mortality rate,” said Mariko Sato, a UI clinical assistant professor of hematology/oncology. “Among the 30 percent of patients whose disease progresses, about half will pass away.”

She said one of the biggest challenges of brain tumors is a membrane that prevents treatment from being effective.

But while the medical world is full of innovations, new brain cancer treatments are lacking.

“I don’t think we have had an innovative chemotherapy drug in the last 10 years.” she said.

In an effort to change this, the children’s oncology group conducts clinical trials in order to find new treatments and therapeutic approaches for children with brain cancer, Sato said.

“In order to find what treatment works, whether that is less radiation or more chemotherapy, we have to work together and make an improvement,” she said.

“[Overall], cancer among kids has improved, and that may be from a lot of different reasons.” said Brian Dlouhy, a UI assistant professor of neurosurgery.

The cancer type’s high mortality rate comes from poor accessibility to the tumor.

“[Other cancerous] areas are more accessible [but] the brain is difficult to access,” Dlouhy said. “Surgery helps, but it is not the cure for cancer.”

As Sato noted, collaboration with others is key to improving the mortality rate. Dlouhy said his role is to provide information from the surgery to the collaborative team and suggest what treatment would be best.

Although leukemia is the second leading cause of death among children, it is still the No. 1 cancer diagnosis in pediatrics, said Arunkumar Modi, a UI clinical assistant professor of hematology/oncology.

Fortunately, Modi said leukemia easier to study than brain cancer.

“It’s easy to do research on leukemia because if you look at cancer cells, you can do that through getting blood drawn,” Modi said. “For brain tumors, you need to do brain surgery, which can be very dangerous to the child.”

This ease of research has led to promising improvements in the treatment of leukemia.

“One of the progresses we made in leukemia deaths is that their survival rate is over 90 percent,” Sato said. “And we get to know more about the disease in the last 20 years, and we have now categorized it.”

Another advantage that leukemia patients have is that doctors are able to categorize the cancer down to the molecular level, so knowing how to approach the cancer is easier, Modi said.

“We have done two things,” he said. “We have given less chemotherapy over the past 15 years, and we have given high-dose chemotherapy and transplant on patients who really need it without giving unnecessary extra chemotherapy.”

Sato said she is hopeful about the future of treatment of pediatric brain cancer.

“With the progress of laboratory data, we would like to make the [mortality rate] slope better and find better treatment [for pediatric brain cancer],” she said. “The exciting part of us working on pediatric brain tumors [is] because I think we are going to make a difference in the future.”