By Tessa Solomon

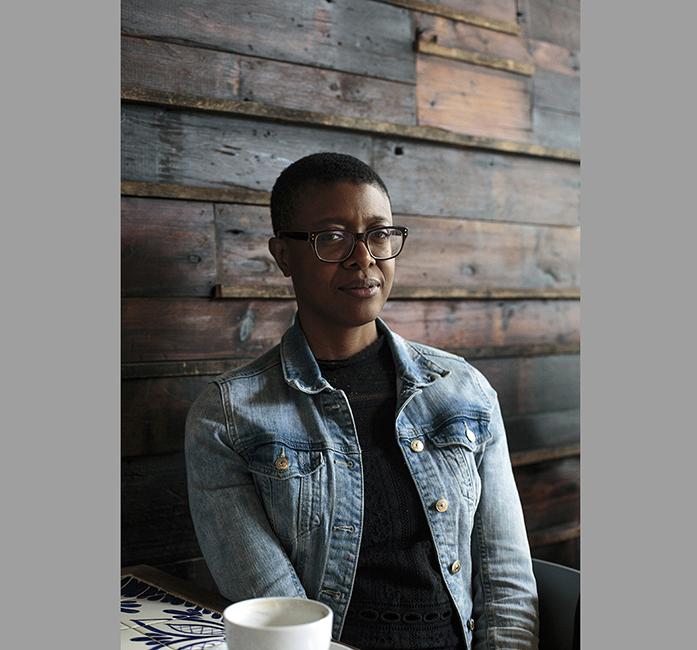

This week, Iowa City’s Center for Afrofuturist Studies — an ever-expanding project in its inaugural year — will welcome its September artist-in-residence, Chicago-based poet and visual artist Krista Franklin.

Her interdisciplinary work explores the history of the African Diaspora and black self-representation through a surrealist lens. Varied in form — poetry, deconstructed bookmaking, collage — her art exemplifies the definition-defying qualities of the unfolding movement of Afrofuturism.

“A goal for the center is to divorce Afrofuturism from the question of genre, which is maybe why it’s such an interdisciplinary project,” said Anaïs Duplan, a Writers’ Workshop poet and cofounder of the Center for Afrofuturist Studies, “and we don’t really choose artists on the basis of aesthetic or genre in that sense,” Franklin’s arrival promises to introduce another voice navigating the various, complex layers of Afrofuturism and partner movement Afrosurrealism.

“It’s important to have her here because not only does she have this joint literary and artistic practice, but also I think she is a great person to teach us about the differences and overlap between Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism,” Duplan said.

Duplan described, with patience, her perspective.

“Afrosurrealism was interested in using the past as a way to understand the present and, to an extent, the future, and Afrofuturism is interested in understanding the present in terms of the future,” she said.

First coined by African-American writer Amiri Baraka, Afrosurrealism could not be pinned to a single movement or style.

Writer D. Scot Miller, in his 2009 AfroSurreal Manifesto — a critical inspiration for Franklin and countless other artists — says, “Afrosurreal presupposes that beyond this visible world, there is an invisible world striving to manifest, and it is our job to uncover it.”

A glimpse of Franklin’s interdisciplinary works helps conceptualize her dreamlike artistic pursuit. In one piece Run DMC — framed by angel wings — overlay yellow and red composition collages and a changeling girl is molded from the creases of paper murals.

Aware of the past, frightened for the present, her poem, “Manifesto, or Ars Poetica #2,” warns, “I believe/that children are the future: love them now or meet them at dusk/at your doorstep, a 9mm in their right hand & a head noisy as a/hornet’s nest later. Your choice.”

It engages sprawling, urgent subject matter.

“I’m thinking a lot about the ways in which African people, diasporic people, and other people of color have used ideas of the imagination, of the speculative, imaginative, to survive white supremacy and colonization over several centuries,” Franklin said.

Franklin’s work does not shy from abstraction or the grotesque; they are boundaries to be pushed — topics of, and beginnings to, conversation.

“Creative arts seem to be one of the few where it’s still relevant to talk about pleasure and emotionality in a serious and critical way,” Duplan said. “We welcome artists who take the conceptual bearings of their art very seriously, though they are interesting flights of fantasy.”

Franklin views the outside world critically but makes it clear that a truly critical gaze is also, and always, focused inward.

“Every day, we should be trying to evolve to some other kind of form, level, whether that [be] intellectual, physical, or spiritual,” she said. “As I grow as a woman in this country, as a woman of the world, I grow as an artist.”

To see examples of Krista Franklin’s work, visit her website.