By Kasra Zarei

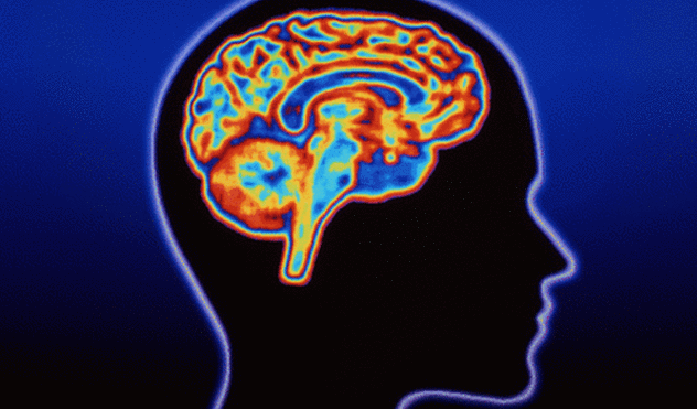

Huntington’s disease is an incurable, fatal genetic brain disorder that creates major emotional, social, and mental tsunamis in the lives of patients and their friends and families.

Because of its inheritance pattern, Huntington’s is a classic family disease in which there is a 50 percent chance that an affected parent will pass on the faulty gene, which causes the characteristic brain deterioration, to her or his child.

“Huntington’s has a major impact on families — the diagnosis of one person is devastating and has ripples through the entire family,” said University of Iowa Professor of psychiatry Peggy Nopoulos, who has served Huntington’s patients for 15 years. “Most people at risk of Huntington’s do not want to find out if they carry the faulty gene. In fact, only 10 percent do, because there is no cure.”

In the past, the UI only saw a handful of Huntington’s patients every month, so Nopoulos and her Huntington’s colleagues established the UI Huntington’s Disease Society of America Center of Excellence.

“Our clinic has continually grown, especially the last five years,” Nopoulos said.

The UI Huntington’s Center gives patients access to other multidisciplinary providers who are experts in this disease, including Shawna Feely, a UI genetic counselor and clinical coordinator, and UI neurology Professor John Kamholz.

“You come for one visit — in that one visit you will see potentially five different providers, including a neurologist, psychiatrist, genetics counselor, social worker, and neuropsychologist,” Nopoulos said. “We are proud to provide this level of care.”

Huntington’s is a rare disease, and the UI center combines research, clinical service, and education to benefit patients in a personalized manner.

“Our Center of Excellence is mainly a clinical entity whose goal is to take care of our Huntington’s patients,” Kamholz said.

The clinic has approximately 200 patients.

“We have large waiting lists and have served as a hub for the Huntington’s patients in the middle part of the Midwest,” Kamholz said. “We now have two treatment teams to help our post- and pre-symptomatic patients.”

The manifestation of Huntington’s is very slow, progressive, and almost always affects thinking and behavior long before it affects any motor skills.

“Often, patients don’t come until they have motor abnormalities, such as involuntary movement,” Nopoulos said. “It’s not uncommon for patients to come for their very first visit when they have had significant, noticeable changes.”

For pre-symptomatic patients, the clinic mainly determines if someone at risk carries the faulty gene, but not all at-risk individuals are eager to find out.

“A lot of people don’t want to know their future like this, that is, when you are 20 you are going to develop a fatal brain disorder later in life,” Nopoulos said.

While there is still much work that has to be done to understand and treat the complex disease, the UI center has also made significant strides in intertwining research and clinic practice.

“Using natural history studies of the disease, we have been able to provide suggestions to our patients that could help delay the onset of Huntington’s,” Kamholz said. “To also help our post-symptomatic patients, we also participate in numerous clinical trials as a center to vet new candidates that could potentially slow the onset of symptoms and give additional years of comfort to patients.”

The expansion of the clinic excites members of the multidisciplinary clinic, including Douglas Whiteside, a UI clinical professor of psychiatry and neuropsychologist.

“This is an exciting development because the expansion of the clinic to a weekly one will reduce wait times for Huntington’s patients and give them better access to these critical services,” he said.

Together, the combined efforts of Huntington’s research and clinical expertise will aid Huntington’s patients for decades.

“Just being able to double our team and offer a weekly clinic is amazing,” Nopoulos said. “Our clinic and work truly embody the importance of making the academic difference.”