Sean Lewis’ new play, Black and Blue, explores the subject of police brutality and opens Friday at Riverside Theatre.

By Isaac Hamlet

Rage is a bubbling, righteous feeling. Like a hot coal burning in your gut, it commands attention. Like a pain-pressured shriek, it demands to be heard.

“Part of it was just pure rage,” said Sean Lewis, the artistic director at Riverside Theatre. “Rage is good. It doesn’t let you sleep. It lets you write a lot more.”

The product of this rage was Black and Blue, a new play débuting at Riverside Theater on Friday that tackles the topic of police brutality.

“What honestly happened is we got the rights to a play about the same subject matter,” Lewis said. “Then the agent contacted us back and said they felt that Iowa City was ‘too small of a market to have that conversation.’ So I tried to find other plays on that subject matter, and I couldn’t find any. I’m sure they exist, I just couldn’t find them.”

He was upset and shocked that an Iowa City stage — or any stage for that matter — could be considered too small to handle a certain subject, particularly one as pressing as police brutality. So Lewis, fewer than three full months into his stint as artistic director, took it upon himself to write a new play.

“When they told me, I thought, ‘That’s insane,’ ” he said. “So I sat down, and I think I wrote 20 or 30 pages [that night].”

That was around six weeks ago. Since then, he estimates that he’s fully revised the script at least once each week.

The premiere of this play marks a hectic beginning to what Lewis hopes will be a future of more inclusive programming for the theater.

After this, the company is slated to stage a satire about women’s roles in politics, a secular holiday piece, a one-woman show from Megan Gogerty about women in comedy, and, to close the season, a show called Relativity about Albert Einstein’s “lost” daughter.

“It’s very easy to program a season of ‘This isn’t going to fail,’ ” Lewis said. “[But] if I think the issue is this important, how do I not program it? I’m friends with a lot of people on Facebook who run theaters and will post about [police brutality], and I think, ‘You have so much of a bigger platform than Facebook, and you’re not programming it.’ ”

Black and Blue is a story about Charlie and Marcus, a cop and a suspect who crossed paths 10 years ago, an encounter that left its mark on Marcus.

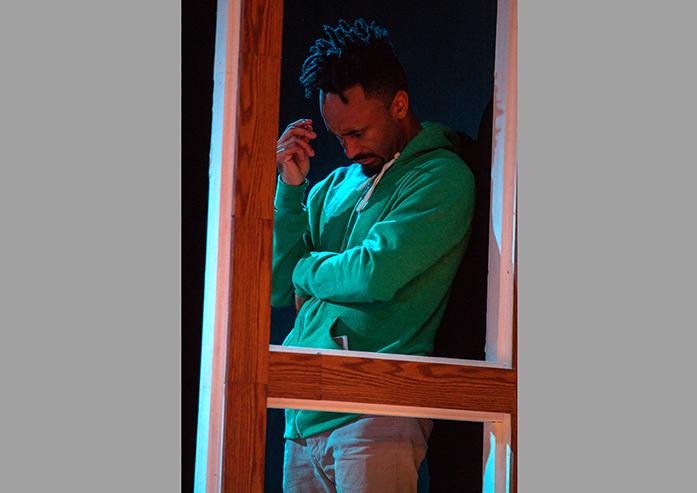

“He’s writing a comic,” said Barrington Vaxter, the actor who portrays Marcus. “He’s not a natural comic nerd or anything like that; he has an affinity for writing down thoughts, because that’s what helps him control the panic attacks he gets from the trauma he endured.”

The play Lewis wrote depicts a world in which black people are superheroes, a world in which the fear police officers have of them stems from the fear of incurring their wrath and waking the giants inside of them.

“He’s forcing himself to believe this because he needs to put the pieces back together,” Vaxter said. “He needs to be a solid human being.”

Also in the mix are Charlotte and Laurie — Charlie’s sister and girlfriend, respectively.

“[Charlotte] is really the instigator of the play in some ways,” said Alyssa Perry, the character’s actor. “She’s trying to bring [the past] back up in a way. She has this idea that may appear hair-brained: to get her brother and the man who’s the victim of her brother together for some sort of reconciliation.”

Though she comes from a family of police officers and has long benefited from the status quo, Charlotte now calls it into question. That’s why, eventually, she persuades Marcus and her brother to talk.

“She’s trying to make the police more accountable,” Perry said. “She’s repulsed by the idea of injustice and unnecessary cruelty, so when she finds out her brother did something horrible, she wants him to be accountable for it.”

It’s because of her that Marcus ends up in a room with her, her brother, and Laurie, the latter of whom Marcus has strong distaste for despite their shared race.

“From Marcus’s perspective, I’m kind of an Uncle Tom,” said Tierra Plowen, the actor playing Laurie. “He can’t believe that I’m really dating a white officer, especially in Chicago.”

In contrast to Marcus’ first meeting with Charlie, Laurie met him after he saved her brother’s life. Thankful for this, she ended up getting to know Charlie.

“You have these characters who sometimes listen to each other and often don’t,” Perry said. “I think it’s refreshing to hear people with different points of view have a conversation with each other. Often, we don’t address things that are going on in our community because we don’t always know what to say. And I think not knowing what to say but trying to say something — trying to have a conversation, anyway — is really important, and I hope that this helps.”

Conversation is exactly what Lewis hopes his play opens the doors for. He intentionally arranged the schedule more like a community calendar in hopes to tackle subjects that will get people talking, even if the opposing sides can’t necessarily see eye to eye.

“With everything going on in America, in the world, I think the phrase ‘Protect and Serve’ has been buried,” Plowen said. “What do we have to do to make people in uniform react less aggressively to people on the street? [Charlie] did mess up, but he was a young rookie cop who’s a human being. Civilians have to realize police are people, too, and police have to be willing to say, ‘Yes, we are people,’ and when they make mistakes be willing to own up to them.”

Conversations such as these helped inform Lewis and the actors as they were delving into the play, a process Lewis has found beneficial, because it forced his actors to dig deeper into the souls of their characters.

“I don’t think [actors] ever know the play better than the playwright, but really good actors start to know the characters more than the playwright,” he said. “At its very best, it starts to be a sort of give and take in the language of the text.”

For Vaxtor, who — like his character — has lived in Chicago, part of the process was making the language of the play come across as honest as possible.

“To curate how a specific population speaks and moves in a way that fits how you’re doing the play, when the play is actually about these people, is to lie,” Vaxtor said. “It’s important to me that the flavor comes across in an honest way. There’s not even a choice.”

It’s this authenticity and relevance Lewis hopes will attract people of every sex and shade to the theater. He especially hopes that it will bring the students out.

“I don’t think this has been a place that students of the university have been very connected to, and that’s such a shame, because you’re all part of the community,” he said. “So part of what I’d been thinking about is how do I program shows that are appealing to all ages? How do I make it so that when [the actors] look into the audience, it’s racially, gender-wise, and age-wise really dynamic — because I don’t know how a community operates without that.”