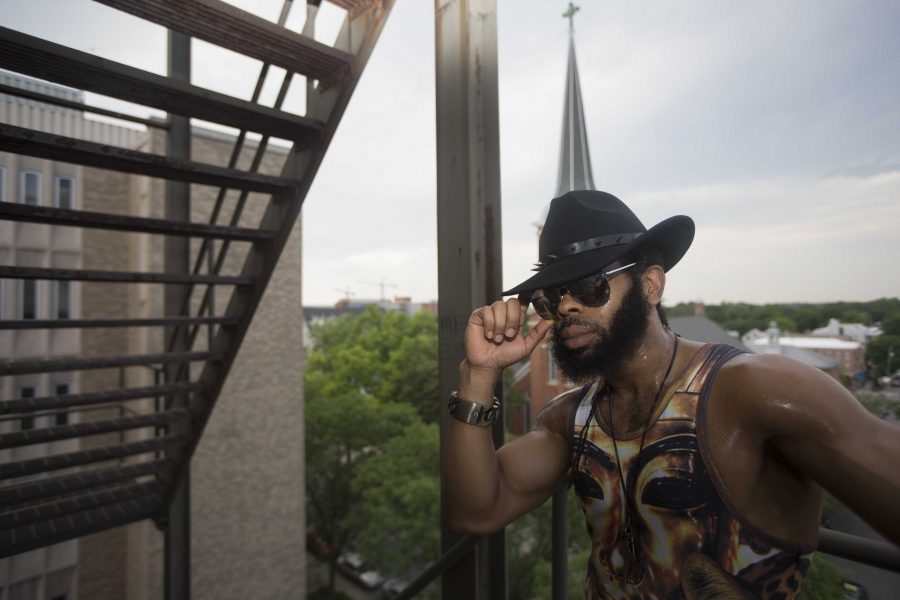

Marcus Brown

Duane Lee Holland Jr., an alumnus of the University of Iowa Dance Department and the newest addition to the Boston Conservatory/Berklee’s full-time Dance Division faculty, has exemplified a trend that would appear to be becoming more prominent. As the first full-time faculty member to be hired specifically to teach hip-hop choreography at the conservatory, Holland has opened a door for the progress of often passed-over aspects of African-American culture as respected fields of study in research in institutions of higher learning. Furthermore, the geographic placement of Holland’s previous academic and professional background in combination with the location of his current appointment reflect the boundary-crossing ability of quality of artistic work and commitment to craft.

When it comes to instances of artistic crossovers between the UI and Boston, Kirsten Greenidge’s play Baltimore, which had a scheduled production at the UI theater last year, comes to mind. In addition to being an accomplished playwright, Greenidge is an assistant professor in the College of Fine Arts at Boston University. Greenidge’s racially informative play Baltimore being shown in Iowa is a quintessential example of institutions of higher learning bridging gaps both geographically and racially to progress issues of social justices plaguing the seemingly exclusive divides between rival ivory towers.

Everything from faculty appointments to choices in commissioned work come together to further illustrate the common ground that can be found in the realm of higher learning despite the arbitrary delineations that can feel all too common within the stratified environment of academia. This holds especially true when it comes to the endeavours of African-American artists, academics, and those that can be described as both.

Because instances of racial insensitivity, discrimination, and outright erasure are at times viewed as isolated incidents in their respective post-racial bubbles of higher learning with no possibility of repetition in an environment with similar incubating factors, the importance of removing borders for African-Americans inhabiting the hierarchical academic space can become understated. It becomes easy to forget that the goal should not be to isolate and dissect these. What is blatantly demonstrated once the façade of academic stratification and illusionary disparity is cast away is, given the opportunity to witness the middle ground present once pomp and circumstance are removed the equation, revealing a holistic and universal to progress into a more hospitable and accommodating environment in which students can learn valuable information, enrich themselves as individuals, with the end of joining society with the skills and experience to better contribute to the society they wish to see in the world. As opposed to being slowly broken down and molded into nuts and gears that further perpetuate a cyclical juggernaut of mass production, capitalism, and ultimately the inability to live life outside of a monolithic institution built upon and fueled the stifled ambition and reluctance to deviate from the inescapable Babylon that has cemented the foundation of this society to such extent that conscious objection could result inability to quite literally become unable to afford to stay alive. Instances as though they happened in a vacuum, when in all actuality the factors and catalytic motivations can be found on any quad or in any student union regardless of geographic location, emphasis of study, prestige, or any other socially constructed means of differentiation.

These pseudo-distinctions distract from the issues that fester in the confines of every dining hall, every dormitory, and ultimately every classroom. It is for this reason that the work of those such as Holland and Greenidge, who are working to redefine the niche-like spaces often reserved for African-Americans and other people of color deserve recognition. The successes of African-Americans in spaces that were traditionally inaccessible and attained without sacrificing the intention and integrity of their craft ultimately produce more than the immediate benefits to the individual and contribute to an ever increasing standard of African-American excellence.