By Justus Flair

[email protected]

[Editor’s note: This story is a part of today’s special issue focused solely on drugs.]

Hunkered down on the floor during a bustling party full of strangers in New York, Caitlin talked to herself, her phone recording every sound.

“I must have looked crazy,” said the 23-year-old poet and playwright. “It was a lot more interesting to me at the time to think about how words sounded together.”

’Shrooms can do that to you. She stayed out of the spotlight, working on her poem for a big chunk of the night.

“A lot of it was awful,” she said. “But there were certain things I could tell, when I heard myself saying them, that I’d never thought of them before.”

The psilocybin mushrooms, a birthday gift from a friend, helped Caitlin in her art. Artists have been trying substances to improve their art for decades, maybe centuries. Edgar Allan Poe used lithium to treat bipolar disorder. Paul McCartney wrote “Let It Be” after a drug-induced dream about his deceased mother. The introduction of mushrooms into the human diet allegedly coincides with the first appearance of cave paintings.

In fact, it’s part of the arts and entertainment industry.

According to a report released this week by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 13.7 percent of adults between the ages of 18-64 in the arts, entertainment, and recreation business used an illicit drug in the past month. This number was second only to the accommodations and food-service industry.

Though it doesn’t work for everyone (“It didn’t help at all, actually,” a UI playwright said. “I’ve heard people are like, ‘Yeah, I did this masterpiece while high,’ so I tried it a few times, and nothing changed.”) Some have found the right drugs can lead to huge improvements.

“When I took them, the stuff I was thinking about seemed a lot less contrived and overdone than I’d thought before,” Caitlin said.

After soberly revising her recorded ramblings, the University of Iowa graduate, who studied theater, writing, and English, had “Long Island,” including the lines “tell everyone/one how you can’t feel your nose /can you ? (feel your knows) / no, buddy —”

“One of the biggest problems I have when writing is I don’t let myself have a first draft,” Caitlin said. “I’ll think, ‘This is dumb, this is dumb, this is dumb.’ But on mushrooms, I was like, “This is genius. This is awesome.’ It was encouragement from my own brain that I never get.”

Though she hasn’t written anything else while tripping out — “I don’t want that to be a thing I need” — she has started using on-the-spot voice recordings as a method.

“When you sit at a computer, it’s easy to erase what you said or rewrite, but when you’re saying what comes to you, it stays the way you said it, and you might find something in that,” she said.

Just as drugs helped Caitlin get out of her own way in writing, they helped 23-year-old actor Boston Dunning, a marijuana enthusiast who studied theater and philosophy at UI, live less in his head. Taking ’shrooms and other drugs, he said, have an ego-shattering effect, forcing a global perspective that helps artists avoid selfishness.

“ ’Shrooms might connect you to an overmind of the entire planet. (It’s wacky, I know),” he said.

Reading a script while high helps him to see the world of the play more fully, he said, rather than being focused in on his character. He’s never performed while on drugs, though, because “audiences want to see the human that is you, not whatever substances you might be taking.”

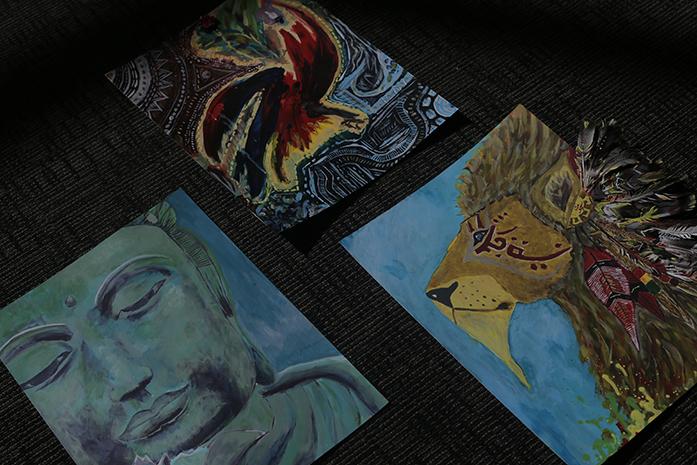

He wouldn’t call himself a painter, but Dunning has made a few visual pieces while on drugs.

“The psychedelic experience is hard to articulate,” he said. “Sometimes, the artists can take the images that they actually see and not have to put it into words; they can make it directly into art.

“I took a bottle of paint, one red and one blue, squirted them on the page, and just started going to town with my fingers. It made a really eclectic painting. It kind of looks like two entities battling, an angel and a demon. It’s in my bathroom.”

Viewers might be limited in that space, but at least the art exists.

“[On acid], all the potential that you have, you can visualize it a little better,” Dunning said. “That’s an inspiring feeling; whether you use that inspiring feeling to make art, that’s all on you.”