By Blake Dowson

[email protected]

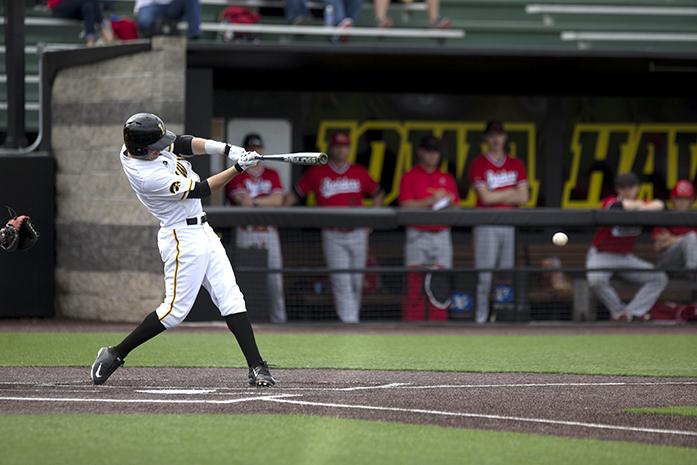

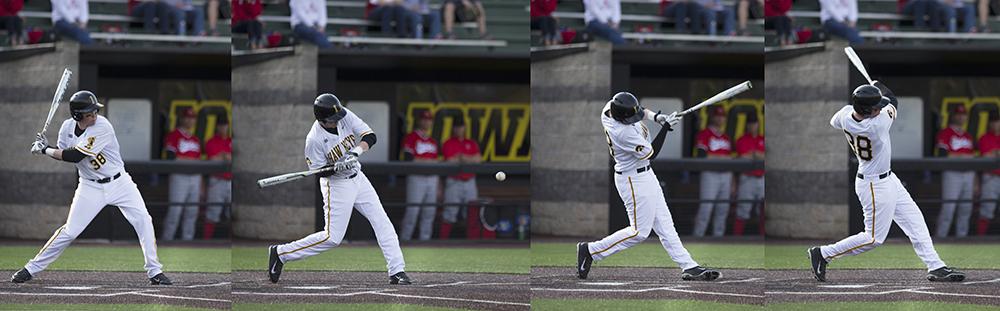

Sure it is disputed, but hitting a baseball is widely regarded as the hardest thing to do in sports.

But what happens when a hitter sits on a fastball, and the pitcher throws him a hook and buckles his knees?

Moreover, what is a hitter supposed to do when he expects off-speed with a runner in scoring position but gets jammed with a fastball?

With a runner on second or third base, the hitter wants something he can take the other way to move the guy over.

A leadoff guy wants to get on base any way possible, while the 3-hole hitter wants to move his leadoff hitter along, which generally means hitting behind him.

Each at-bat, each pitch, brings new challenges for a hitter, and his approach changes every time the catcher squeezes the pitcher’s latest offering.

Concocting an approach at the plate can be a science of sorts, but coaches also do not want their hitters thinking too much at the plate.

For Hawkeye head coach Rick Heller, simplicity in the box is the goal.

“There are really three approaches that we look for in our guys,” Heller said. “We have an ahead [in the count] approach, where you’re really just trying to get your best swing off. Then you have a two-strike approach, and then the other is a situational approach when we hit and run or bunt.”

Heller, a numbers guy, also looks at the analytics of an at-bat and lets the percentages determine the approach his players should take with them up to the plate.

For the casual baseball fan who may not understand analytics but has seen Moneyball, remember Brad Pitt uttering over and over, “But can he get on base?”

“My big thing with our hitters is trying to have a high on-base percentage,” Heller said. “That’s always been one of the things we’ve tried to do. We don’t worry so much about the batting average. We want to cut down our strikeouts and increase walks.”

But of course it is not as easy as just sitting fastball or curve ball and whaling on it. The guy on the mound is working equally as hard to keep the hitter off-balance.

A hitter’s approach changes after each pitch is thrown. When Iowa senior leadoff hitter Joel Booker digs in for the first pitch of the game, he is looking for one thing.

“I’m looking for a fastball elevated that I can drive so I can get on base,” Booker said. “My role in that leadoff spot is to get on base and make the pitcher sweat. I want him to make a mistake to our 2-hole hitter.”

As early as the second pitch of the game, a leadoff hitter can change his approach, depending on what the pitcher started him out with.

“You lock in a little more if you go down 0-1,” senior Corbin Woods said. “You want to stay even-keel as much as you can, but you look for that one pitch you can drive.”

Booker’s role as Iowa’s leadoff hitter is different from what it would be if he were playing at most of the other Big Ten schools.

Heller teaches a nontraditional approach in the leadoff spot, an approach based on contact, not walks.

“What we teach [of the leadoff spot] is kind of contradictory to what common thinking is,” he said. “You think leadoff, you think a guy that takes a lot of pitches and walks a lot. I think of it the other way. The leadoff guy is the one the pitching coach is telling to attack, because he works walks, so he’s going to get quite a few good pitches to hit. To me, a good leadoff guy isn’t going to walk a lot and isn’t going to strike out a lot.”

Once Booker is on base, Heller wants to move him up without wasting an out. The analytics guys will say the best way to do that is to swipe a bag, not bunt.

“In our system, we aren’t a big sacrifice-bunt team,” Heller said. “Going back to analytics, we don’t like to give away outs. We’ve been fortunate that both Eric [Toole] and Joel [Booker] can steal a lot. That’s usually dictated by the stopwatch — how fast the pitcher is to home plate, in combination with the catcher’s time to second base.”

With a runner making his way station to station in front of him, senior Tyler Peyton’s approach changes with each 90-foot advance.

“I prefer hitting with guys on base,” Peyton said. “There’s a sense of comfort there. If there’s a runner on third, I’m looking for an off-speed pitch. Sitting in that spot, they’re not going to throw you a fastball belt-high. So I look for an off-speed pitch left up that I can drive to the outfield.”

As a hitter works and gets deep into a count, his two-strike approach may be the most important.

Guys who put a lot of balls in play are going to get on base more than guys who don’t have an idea of what they want to do with two strikes.

“We’re taught to sit fastball outside,” Booker said. “If you think opposite field and you think fastball, then you’re able to adjust to the off-speed pitch and shoot it the other way. If you get jammed with a fastball, you, hopefully, fight it off and stay alive.”

As different as each at bat, and each pitch, is for a hitter, there are a certain number of constants that Heller wants his hitters taking into each plate appearance.

Numbers don’t lie, after all, and the Hawkeyes like to look at trends to determine what they do at the plate.

“As a general rule, we talk about how most guys want to pull the ball,” Heller said. “But in reality, if you look at the charts, 75 percent of the pitches you see are middle and away, so it makes a lot of sense to go up there looking for a pitch middle-away that’s elevated so you can drive it to the opposite field.”

Follow @B_Dows4 on Twitter for Iowa baseball news, updates, and analysis.