Animals-rights activists continue to question the constitutionality of so-called ag-gag legislation prohibiting undercover investigations of livestock operations. While Iowa’s law has not come under fire for violating the Constitution, animal-rights activists say it is particularly restrictive.

Rather than banning filming or photographing, as Idaho, Utah, and North Carolina have done, Iowa’s law — House File 589, passed in 2012 — targets those who lie about their history or intentions in order to get inside a production facility. Alicia Prygoski, the Humane Society of the U.S. public-policy coordinator, said the nature of Iowa’s law makes it nearly impossible for an investigator to get on a farm.

Animal-rights groups have criticized such legislation, arguing it violates the First Amendment. But, said Laurie Johns, the Iowa Farm Bureau public-relations manager, producers worry about being targeted by groups looking to put them out of business.

Animal-rights groups have criticized such legislation, arguing it violates the First Amendment. But, said Laurie Johns, the Iowa Farm Bureau public-relations manager, producers worry about being targeted by groups looking to put them out of business.

“It’s pretty easy in any industry to find the worst-case scenario and blow that out of proportion, like that’s … mainstream agriculture, when that is clearly not the case,” said Mike Telford, the executive director of the Iowa Animal Farm Care network. “The Humane Society of the United States, as well as PETA … it appears that their goal is to stop all meat consumption and all animal production. You’ve got people with an ax to grind … and they’ve misrepresented themselves.”

But animal-rights activists argue the issue of transparency lies with the livestock industry.

“Americans have a vested interest in knowing that their food is being produced safely,” Prygoski said. “Unfortunately, due to agribusiness lobbying, there is virtually no governmental oversight of these farms in the country.”

While state and federal governments perform inspections and enforce regulations on the conditions of livestock facilities, few laws cover the welfare of livestock animals.

At the state level, Iowa Department of Natural Resources regulations focus largely on environmental health concerns, and the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship only performs inspections of companion-animal breeders, such as dog breeders.

“If there are concerns about animal abuse or neglect, folks can report that to their local law-enforcement officials,” said Dustin Vande Hoef, the communications director at the Iowa Agriculture Department.

At the federal level, the Animal Welfare Act, enforced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, does not apply to animals used for “fiber, fur, or food,” said Tanya Espinosa, one of the inspection service’s public-affairs specialists.

According to the Animal Legal Defense Fund, there are no federal laws governing the conditions under which farm animals are raised. The only federal regulations apply during transportation and the time of slaughter.

Vehicles transporting animals to slaughter are required by the 28-hour law to stop every 28 hours to give livestock food, water, and exercise.

“The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act applies, as the name suggests, only at the time of slaughter, and it excludes poultry,” said Vandhana Bala, the general counsel for Mercy for Animals.

Prygoski said investigations conducted by the Humane Society before the laws were introduced prove there was a need to know what goes on behind livestock facilities’ closed doors.

Examples of abuse alleged by the Humane Society’s investigations include the forced cannibalism at Kentucky’s Iron Maiden Hog Farm or the situation uncovered at Hallmark Meatpacking Co. in Chino, California, in which sick downer cattle were used in the nation’s school-food supply.

But, Telford said, Iowa producers have a vested interest in keeping their animals healthy and generally do an excellent job of caring for their livestock.

“The only way you have animals that produce well is if they’re very well-cared for and very comfortable,” Telford said.

In addition, the Iowa Farm Animal Care network works to promote responsible, humane care and provides a help line for those with concerns.

Telford said most calls come from producers with questions and have to do with isolated incidents.

“Say there’s an operation and animals are being mistreated — for example, a horse that’s not being well-fed — and it’s not really even a production situation,” he said.

If a situation requires further attention, the network works with the Iowa Animal Rescue League and members of Iowa State University Animal Science Department and veterinary medical staff to perform an evaluation.

“They give a full report to the … owner of the animal so they can follow up,” Telford said.

Despite the promotion of best practices, animal-rights activists insist there is still a need for their investigative work.

“It’s important to note that ag-gag bills don’t just threaten animals,” Prygoski said. “They threaten factory-farm workers, journalists, the environment, and public health.

“At the end of the day, 70 different interest groups have opposed one type of ag-gag bill or another.”

The Humane Society has helped defeat more than 30 bills across the country in the past six years.

Prygoski said the success of an agriculture bill usually depends on the kind of restrictions mandated. Recording bans have proven to be particularly unpopular. Currently, North Carolina, Iowa, Missouri, Utah, Alabama, and Kansas have agriculture laws in place.

Until recently, Idaho was also counted among those states. Idaho’s law, the Agricultural Security Act, punished undercover animal-rights investigators with fines and prison time. It was struck down in 2015 after a federal district court judge found the law violated the First Amendment.

Utah’s legislation provoked a similar backlash in 2016, when PETA and the Animal Legal Defense Fund led a lawsuit contending that the law violated the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.

The challenges to Idaho’s and Utah’s laws are currently pending in the 9th and 10th Circuits of the U.S. Court of Appeals.

Prygoski said there is a need for investigative work, and only increased government oversight might justify what she refers to as ag-gag laws.

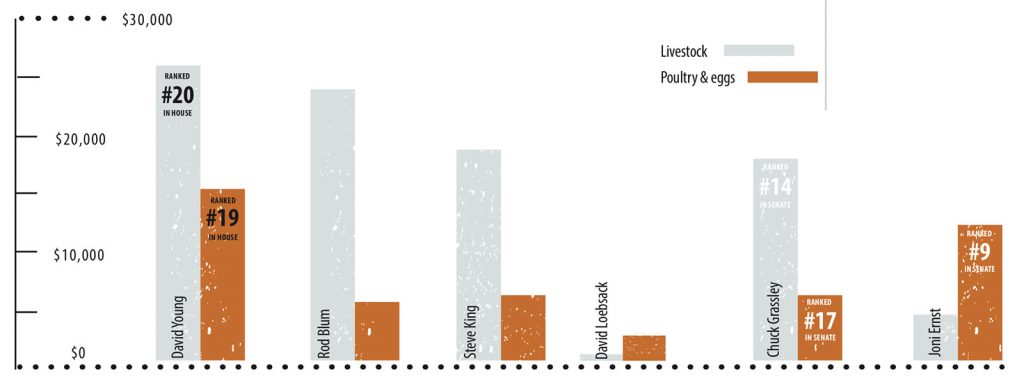

Money received from agriculture interest groups