Obama’s shadow looms over the Clinton-Sanders divide.

By Brent Griffiths | [email protected]

Former Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton challenged Americans in saying, “Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow” as his Third Way politics swept from the South to the nation’s capital.

Barack Obama, a young former Chicago community organizer, preached about the promise of hope and change and rode it to the White House.

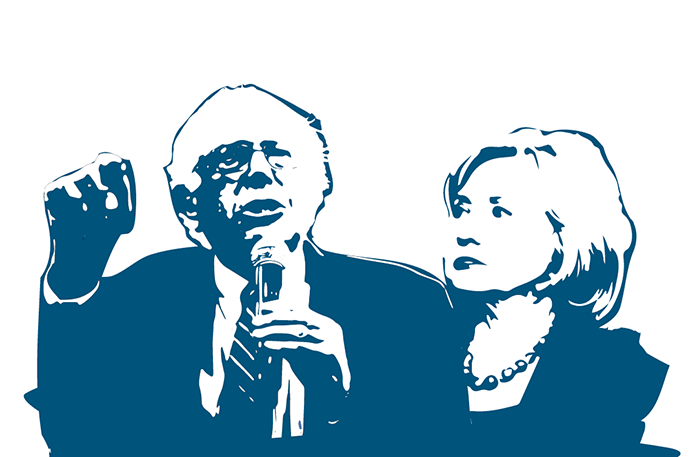

And now, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders shouts about needing a full-scale political revolution while former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton plans a path ahead as the protector who will keep the crazies, by her portrayal, out of power.

In their ads, speeches, actions, and at the very core of each campaign rests a divergent choice for the future of the Democratic Party: full-scale revolution or achievable reality.

“I think they have two different approaches,” said longtime Iowa Democratic strategist Jeff Link, who counts himself as a Clinton supporter. “One is sort of grounded in reality, and one is sort of grounded in fantasy. The fantasy approach doesn’t seem to be as crazy as it sounds.”

Clinton, the self-described progressive who says she likes to get things done, tells Iowans she does not want to over-promise what can be accomplished. When she held her first big rally over the summer outside New York City, she spoke of securing the gains of President Obama.

Just a few months after that rally, while Donald Trump transfixed the national media, Clinton told a group of Black Lives Matters protesters her mantra for government.

“I don’t believe you change hearts,” Clinton said backstage after a campaign event in New Hampshire. “I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate. You’re not going to change every heart. You’re not. But at the end of the day, we can do a whole lot to change some hearts, and change some systems, and create more opportunities for people who deserve to have them.”

Experts who study the state caution that the Iowa Democratic Party has a strong progressive base that bucked Clinton eight years ago in favor of Obama or then-North Carolina Sen. John Edwards. And while Clinton’s argument can generate some enthusiasm, she still is part of the much-maligned “establishment.”

“She can be leadership, experience, but she is not really change — other than the historic nature of the election,” said Christopher Budzisz, the director of the Loras College Poll.

For many Iowa Democrats, Clinton’s words encapsulate some of the disappointing realities of the last eight years.

“This has been a very discouraging eight years in terms of what has been accomplished in terms of what needs to be accomplished,” said Martin Olive, the chairman of the Adams County Democrats. “At some point, the problems we face today have to be addressed.”

Obama’s executive actions, which have addressed topics ranging from coal-fired power plants to pushing back against for-profit colleges, are a start, Olive said. But more needs to be done.

Enough of those Iowa Democrats believed in the Illinois senator to surge behind him on a historic caucus night in 2008; he won with 940 state delegate equivalents — Democratic caucus results are not reported in raw vote totals. Obama promised to unite a nation, but those same Iowa activists watched as Republicans became a recalcitrant opposition that fashioned itself as the roadblock to progressivism.

Sanders has a different mantra. And a possible cure to the frustration that Obama did not go far enough.

You can’t listen to Sanders for more than a handful of minutes before the talk of a revolution rolls off his tongue as if it’s 1776 or the Beatle’s “Revolution” is playing in the background.

The democratic-socialist’s push for a full-scale revolution comes with promises of big-bank busting, universal health-care coverage, and end of big money.

But for someone who examines Iowa politics and the state’s caucuses closely, the choice of Sanders as vessel for Democratic anger appears odd. David Redlawsk, a Rutgers University political-science professor who is back in Iowa as a fellow at Drake University, said the caucuses have always been a party event, an odd place for someone such as Sanders, who in the past has refused to even be considered a Democrat.

“There are surprising number of people who have spent years building the party as party leaders and are working for a guy who has never built the Democratic Party,” Redlawsk said. “The desire for the message just overrides everything else.”

The kind of hopes Clinton has taken to saying would not oversell. She is the progressive who likes to get things done. The former New York senator said she waited for her revolution, especially on health-care reform, but it never came.

Peel back a recent poll of likely Democratic caucus-goers, and you’ll see this divide close up. When CNN asked 280 Iowa Democrats how they would rate the last eight years of Obama, 33 percent said they would want the next president to have more liberal policies. But 48 percent would welcome continuing the president’s policies; there was a 6 percentage point margin of error.

When it comes to the top-two candidates, Sanders and Clinton, the complexities become even more apparent. In the same survey conducted from Jan. 15-20, 57 percent said the Sanders best represented the values of Democrats. Despite those feelings, 60 percent of respondents said Clinton would be best suited to represent the party against a Republican come November.

One issue that illustrates the disagreement in action is health care. Sanders has for years championed a Medicare-for-all system that would enshrine a single-payer system, widely popular among liberals. Clinton chides the pursuit of such an agenda, which she has said could lead to a rehashing of the drawn-out health-care debate that led to Obamacare.

“The ultimate goal, long-term, is Medicare for all health care for all system,” said Katie Dodge, the chairwoman of the Allamakee County Democrats. “For the Democrats I know, Medicare for all is the ideal, but getting there is a very, very difficult thing when the current way of delivering health care in our country is entrenched politically and economically. What I see are small steps that will take a long to time to get to that.”

Clinton, Dodge said, recognizes many in her party would have never supported the insurance-centric Obamacare before it became law.

Even though Obama won’t receive a single delegate on caucus night, Iowan Democrats face a decision. A choice between someone like the sanguine senator they fell in love with or the president he became.

“They’re disappointed that Barack Obama didn’t change the world,” Redlawsk said about the state’s progressive core. “And here is Bernie saying that he can change the world, and they are ready to try again.”