Christopher Cervantes

[email protected]

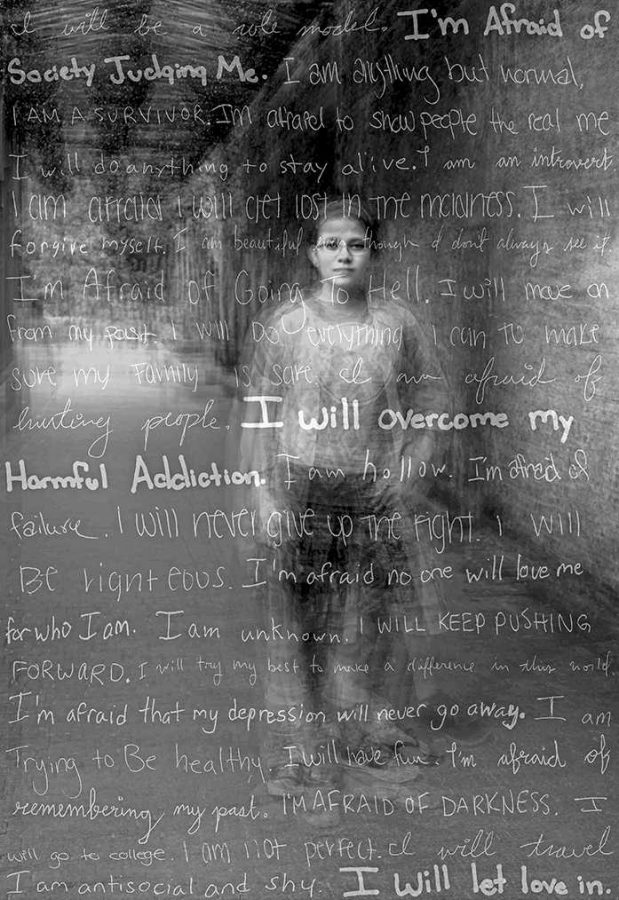

On Oct. 1, artist and activist Traci Molloy visited the University of Iowa campus and spoke about her various projects and works. Molloy was a key figure in several group efforts, such as (but not limited to) Kids that Kill Kids, Our Lives Matter, and the America’s Camp Collection. Through her efforts, she has not only driven to assist children who lost a loved one in 9/11 but also tackled issues of “bullycide” (suicide attributed to bullying), as well as school shootings. Molloy did bring up an interesting point during the middle of the lecture. When she spoke about her work on Kids that Kill Kids, she noted that the exhibit was dedicated to the victims of the incidents rather than shining a spotlight and inadvertently glorifying the killers. When she said that, it really hit me just how true those words were.

Whenever a tragedy strikes at the heart of our nation, the inciting incident absorbs the attention of the masses and fastens the memory of itself to all who care to listen, as the recent mass shooting in Oregon has shown. However, when it comes to the news coverage and what grabs the audience’s attention, several important factors and details are lost in the informative translation.

Take, for example, one of the most infamous serial killers in the history of my home state of California, Richard Ramirez, a.k.a. the “Night Stalker.” Even if you just mention his moniker, recognition is the immediate reaction. However, if one was put on the spot, I doubt he or she would be able to recall a single name of one of his victims. We are so busy remembering the atrocities of a horribly deluded man that the memories of the deceased are forever clouded by the connection they have with a diagnosed sociopath. Their families may remember the victims well enough, but for the rest of the general public, they are simply a number.

How did we get to this point? When did human life, in the grand scheme of things, simply become a statistic? I believe Molloy holds the answer.

I asked the artist how she was able to deal with the harshness of the subject matter and not grow disheartened. “I don’t take my work home,” she said. “I care about what I’m doing and the people involved, but I separate my professional and private life. It is a necessity.”

That statement, whether intentionally or not, explains it all.

When an everyday person catches wind of a tragedy, that person will (most likely) not have any active role in the circumstances surrounding it. The tragedy becomes information that follows us around and attaches itself to the everyday thoughts. If you break the victims down into names and familial relations, then the magnitude truly sets in. Consequently, by focusing on the perpetrator, one person, the empathetic enormity seems to lessen, making the processing less painful for the Average Joe.

The world is not always a good place. With every glimmer of light, there is always a darker shadow. Sometimes, people just try to feel the hurt as little as possible and focus on what makes it easier to carry on. It’s a theory, anyway.