With walls painted in a calming green, comfortable furnishings, and paintings hung on every wall, Gay & Ciha Funeral and Cremation Service feels like a friend’s living room rather than a death care facility.

Dan Ciha is one of Iowa City’s two core providers of funeral care. The now-64-year-old has worked at the funeral home for over 40 years, beginning as a 16-year-old after a high school field trip.

He didn’t intend to enter the funeral industry; Ciha wanted to be a veterinarian at first, but joked that one must be smart to be a vet.

“You don’t have to be smart to be a funeral director, and I’m living proof of that, but in all seriousness, our class came through the funeral home and I thought, ‘Well, this is kind of interesting,’” Ciha said.

His high school class received a tour from the lead funeral director of the establishment, George L. Gay. Ciha said his teacher called Gay the next day, who then interviewed Ciha and lined him up for a summer job.

Eventually, Ciha was exposed to all the various jobs in the funeral practice and decided to officially enter the profession. He attended Kirkwood Community College before traveling to Texas to attend the Dallas Institute of Mortuary Science and received his funeral director’s license soon after.

Mortuary science and licensure

Currently, the only certified mortuary science program in Iowa exists at Des Moines Area Community College, which is entirely online. While many schools offer prerequisite courses like basic biology, including the University of Iowa in its mortuary science preprofessional program, much of the state lacks a direct track to mortuary licensure.

In an email to The Daily Iowan, Kevin Patterson, the program chair of mortuary science at DMACC, wrote that there are currently 206 students enrolled in the virtual program from 25 different states.

From 2014-21, DMACC enrolled about around 150-175 mortuary students every academic year. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the program switched to an entirely virtual option, which allowed for an increase in students.

DMACC’s Mortuary Science program enrolls students in traditional courses and hands-on work to prepare for licensure, Patterson wrote. This instruction includes how to communicate with grieving families.

“While some media sources may paint a negative stigma around funeral directors, they provide a service to families who are facing one of their lowest points in life and help them as they begin the grieving process,” Patterson wrote.

It takes four years to become licensed as a funeral director in Iowa, Patterson wrote.

Licensure must be acquired through a mortuary science program from a school accredited by the American Board of Funeral Service Education. A one-year internship is also required, as well as passing the national and state board licensing examinations.

According to their website, the Iowa Funeral Directors’ Association represents over 700 licensed funeral directors, with nearly 85 percent of those licensed in Iowa, and the other 15 at out-of-state schools. There are 425 funeral home establishments throughout the state.

Ciha noted that licensure requirements vary by state. Iowa used to require a dual license: an embalmer’s license and a funeral director’s license. The term “embalmer” is interchangeable with “mortician,” Ciha said, though both terms are fairly old-fashioned in the industry.

The state of Iowa abolished the dual licensure system over 60 years ago, combining the two because both were required to practice in Iowa. Other states like Missouri continue to mandate a dual license. The key difference, however, is that an embalmer’s license requires a full four-year term of secondary education, while a funeral director’s license does not.

For example, Ciha said, someone in Missouri can graduate high school and immediately become a funeral director, which means they are then licensed to handle the deceased, but not to specifically embalm.

In 2018, this difference in education requirements became a topic of discussion in response to a decrease in licensed funeral directors in Iowa. The IFDA considered making a bachelor’s degree required to obtain licensure in Iowa, but no progress has since been made.

While mortuary science doesn’t require the same amount of intense training as becoming a doctor, for example, it still requires certain unique traits, Ciha said.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist, and when I say that, I don’t mean it in any demeaning way,” Ciha said. “You have to love people and you have to have the passion to take care of them at all times of day and night.”

He expanded upon the workload of the average funeral director, describing the hours as “horrific.” Ciha said funeral directors rank high in terms of burnout and exodus, or leaving the profession early in one’s career. He also noted that the profession ranks among the highest for rates of alcoholism.

Even when someone dies unexpectedly, Ciha must be ready to go, even if in the middle of something like family dinner.

“You go to work at that point, and you leave your family at the table and you might see them in six hours. So, that’s the part that sucks,” Ciha said. “[The job] is just very hard on an individual. It’s hard on your families, your personal life.”

Despite the stress and fatigue that can come with his career, Ciha said he “wouldn’t trade it for the world.” He noted that the relationships he forms with families and individuals make it worthwhile.

In some cases, families may bury up to five generations with the same funeral home, Ciha said.

“The thing that I so appreciate about our work is families not only trust us with their dear loved ones, but they trust us with their families,” Ciha said. “I can tell you stories about families, but I never would. They trust you like a counselor. And there’s some things I wish nobody ever told me, but they tell me. And it’s cool because they trust me with that.”

Rise in cremation, decrease in burials

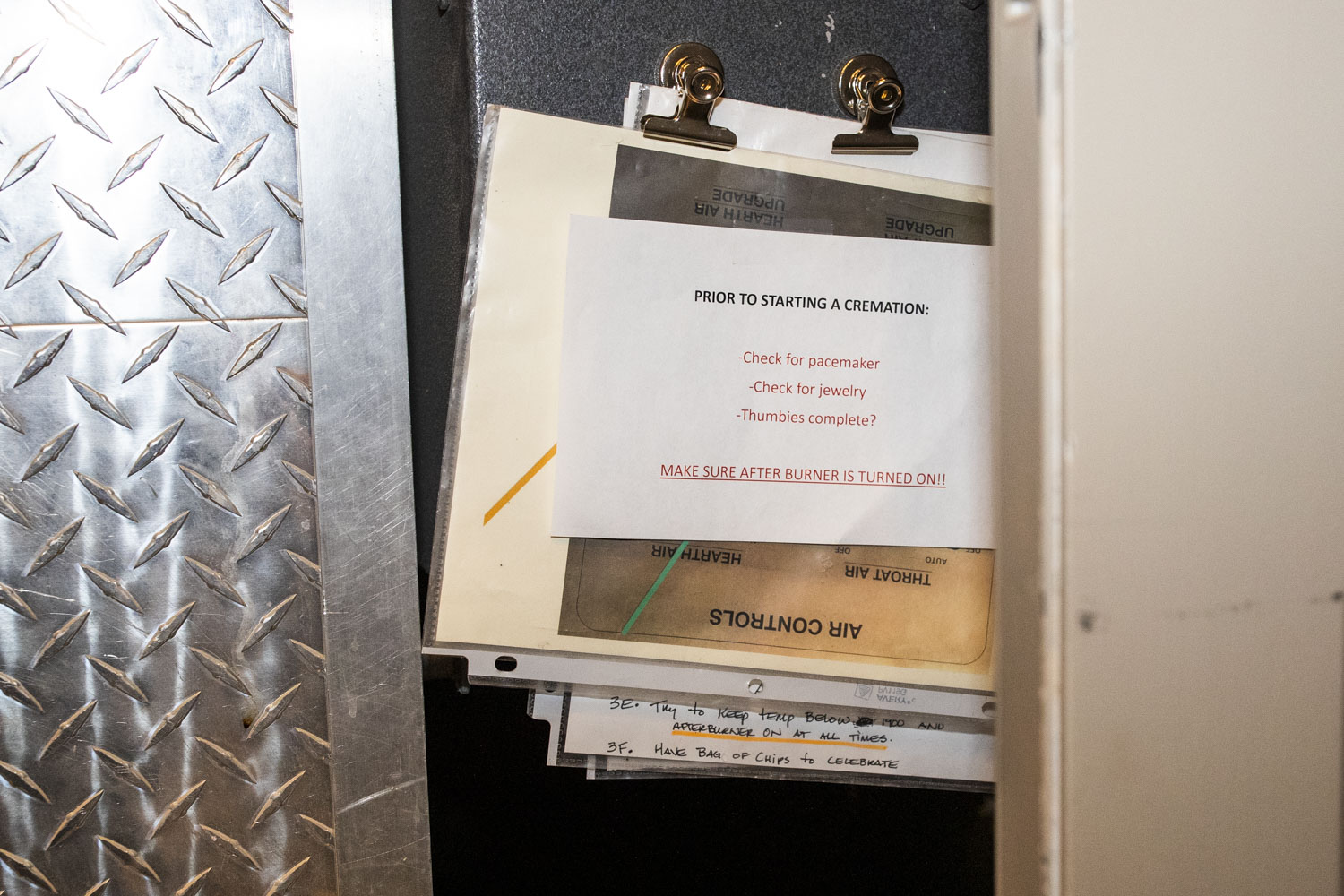

Ciha said there has been a massive increase in cremations in recent years. When he began as a funeral director in 1976, the home’s rate of cremation was less than 1 percent.

Now, the rate of cremation Ciha sees is almost 70 percent, he said. However, the reasons behind this drastic increase vary. For one, he said younger generations examine everything, including death, in a slightly different way than older generations, including but not limited to religion.

The other core provider of funeral care in Iowa City, Lensing Funeral & Cremation Service, currently sees a rate of about 58 percent cremations, according to co-owner Michael Lensing. Lensing Funerals also has a location in Coralville with a pet cremation service.

These estimations are backed by the National Funeral Director’s Association, which reported that the average U.S. cremation rate was 60.5 percent in 2023. The NFDA expects this percentage could increase to over 80 percent by 2045.

“In my experience, cost is not always the main reason,” Lensing said. “I feel it is the desire to be cremated. Cremation has become more acceptable over the years. Most religious denominations have given their approval, however, we find less cremation with Jewish families and no cremation with Muslim families we serve.”

However, cost still plays a major role for many. The NFDA reported that 54.4 percent of surveyed individuals cited cost-effectiveness for why they would choose cremation over traditional burial.

Without a cemetery plot, headstone, or embalming, among other burial services, thousands of dollars can be saved in the death care process. According to a document listing the prices for various service options that Lensing provides, their general full-service burial funeral package costs $7,495. Their general full-service cremation and funeral package costs $5,640.

There are also more general options associated with cremation, Ciha said, citing one unique example.

“For instance, I had a gentleman, he was a big Harley Davidson buff,” Ciha said. “I mean, he rode his Harley all over the country. He probably had easily, 200 biker friends just locally, and when he died, his daughter said, ‘I want Dad to go all over the country.’ So we did 150 little baggies of his cremated remains. And all the guys that showed up at the old Mill for the celebration, they all took a baggie of his and decided where they were going to spread them. So, you can’t do that, obviously, with a person in the casket.”

Ciha himself views cremation as an acceleration of the deterioration process. He said even in a sealed casket, we all return to our natural elements eventually. Cremation simply accelerates that process very quickly.

“A lot of people like the idea that they’re not just ‘sitting around rotting,’ as they would say,” Ciha said.

Green burials

Aside from traditional burials or cremations, the concept of the “green” burial has also increased in popularity. According to the NFDA’s 2023 report, 60 percent of surveyed individuals would consider a green burial option, up from 55.7 percent in 2021.

Ciha said green burials usually occur without embalming, and therefore must be performed within three days of death because of state requirements. Typically, Ciha said, green burials take place in green cemeteries, which allow the deceased to be buried without a casket or burial vault.

A burial vault is an underground concrete container that protects the casket and the deceased inside. A green grave is typically not as deep as a traditional grave, because of the lack of a burial vault.

Green burials are intended to be environmentally conscious, as they take up less physical space, and don’t allow for the leeching of chemicals into the ground from embalmed bodies. According to an Environmental Protection Agency report, formaldehyde leftover from embalmed bodies can cause harm to animals and can be found in ambient air, contributing to overall pollution.

Ciha said he thinks green burials are a great concept, but that the practicality is often difficult because of cost and a low number of nearby green cemeteries.

“It’s kind of like organic bananas versus the regular bananas,” Ciha said. “We want to buy the organic because it’s better for us. It’s better for nature and all this. But for some strange reason, they cost more.”

He estimated that the cost of a green burial is equal to or slightly less than a cremation. According to the NFDA’s 2021 cost report, the median price of a funeral with burial and full viewing service is $7,848. The median price of a funeral with cremation is $6,970.

While the total cost of a green burial varies, the average cost of a green burial casket — usually an untreated wooden or wicker casket — is $1,500. Combined with the cost of transportation and the potential price of a green grave, the average price can reach $3,000 to $5,000.

Ciha noted there are no green cemeteries near Iowa City, though some nearby cemeteries do allow for some natural burials without embalming or a casket. However, he said the cost would be much higher to purchase a plot of land at a green cemetery than at a city cemetery because most green cemeteries are privately owned.

“If I won the lottery, I would have said I was going to buy 150 acres around here and just have a green cemetery,” Ciha said. “But the problem is you got to have quite an investment in the land and you got to pay for that investment. So the only way you can do that is to charge like a son of a gun for that piece of land and charge to open the grave and close the grave.”

Destigmatizing death

Perspectives on death vary across age, life experience, and personal relationships. Regardless, death will eventually apply to everyone.

Lensing, who has worked as a funeral director for 47 years, said he has served countless families with different views on the services he provided. For some, the loss was a celebration of a long life that was well lived. For others, the death was a life cut short because of war, an accident, a suicide, or a premature birth.

“I believe that to move forward through the grief process, it is essential to stop and mourn the loss. Ceremonies and rituals are lifesaving,” Lensing said. “People want to ‘celebrate a life,’ but one must say goodbye before you can celebrate.”

Ciha said he doesn’t believe we are meant to have all the answers about death. While he said he fears dying, he doesn’t fear death.

“What’s crazy is you’re born, you’re going to die. There’s no way around it,” Ciha said. “And there gets to be a point where you welcome death as peace and it’s not the enemy. When I was 20 years old, I probably thought, ‘I’m going to live to 85.’ No big deal. As I get closer to that 85 point, I want quality, not so much quantity, but like I said, I’m not scared of it. It’s just how I get there.”

He said the media has “done its own spin” on death, especially when it comes to concepts like spirits or ghosts. However, Ciha said he thinks about every deceased individual as someone’s family member. He never refers to the deceased by the term “dead body,” instead calling them by name.

Whenever he is asked about how he can love his job working around “dead people,” Ciha said he always flips the question.

“People say, ‘How can you be around the deceased like you are?’ And I say, ‘If that was your grandfather, would you call them morbid or gross or distasteful?’ And they say, ‘Well, of course not,’” Ciha said.

In regard to his own death, Ciha said he wants to be cremated so his family could take him to different places if they chose.

Lensing, on the other hand, would prefer to be buried in a traditional service with a Christian mass and burial.

Ciha said there is ultimately no right or wrong answer to how to think about death, or how to go about choosing death care options. He said funeral directors must put the deceased’s wishes first.

“My mother’s in three different places, and she was cremated. My dad is buried in a cemetery in Solon in a casket,” Ciha said. “And that just shows that people can be different and there’s no right or wrong here. It’s wrong if we don’t do what they want us to do.”