Despite rereading “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” every year since I first picked up the book at 13 years old, I didn’t consider it controversial until I noticed its title on a list of 68 books removed from the Iowa City Community School District.

Senate File 496 restricts literature available to public school students in Iowa with an emphasis on banning books containing “depictions or descriptions of sex acts.” The law was signed in May, and Iowa City schools removed the banned books in October.

Personally, many of the removed books from Iowa City schools informed me of different identities and cultures.

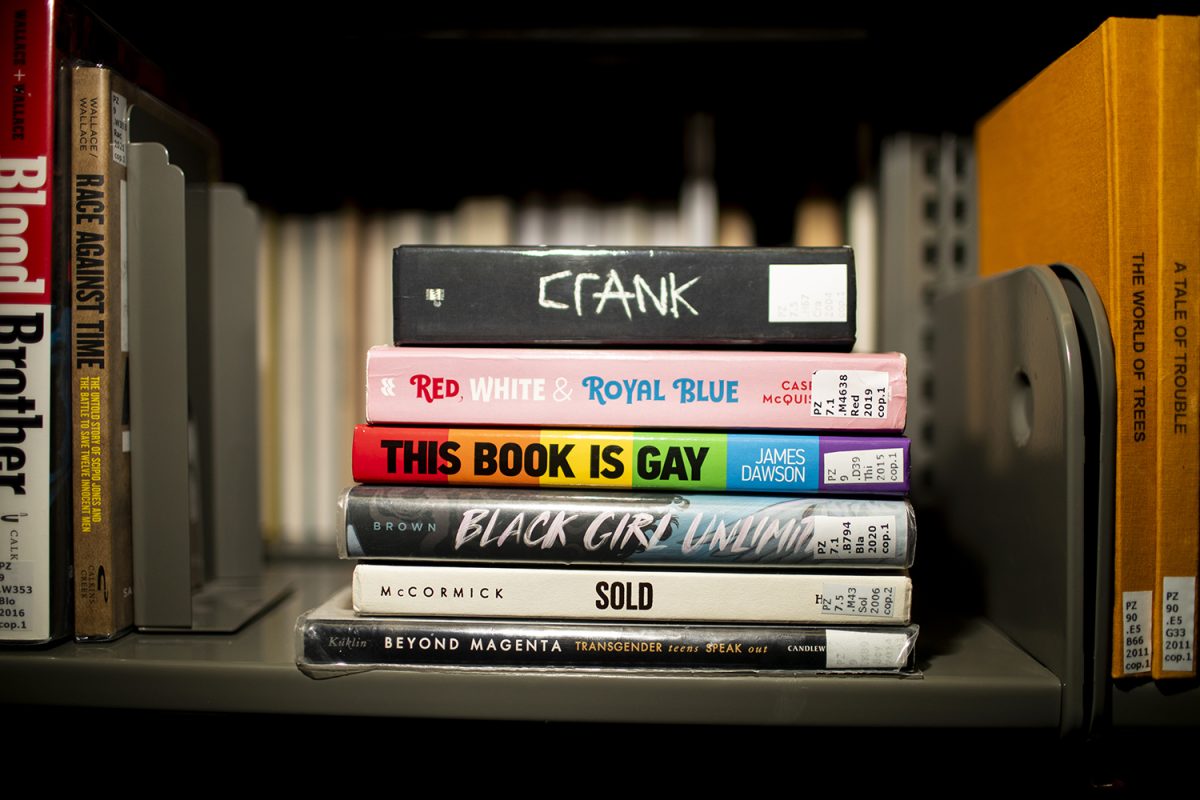

The list includes titles such as “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” “Red, White, and Royal Blue,” and “Song of Achilles.”

Gov. Kim Reynolds argues that students and teachers deserve tools to succeed rather than face distractions in books, she said on Oct. 25.

Sex is not anywhere near what comes to mind when I think of “The Perks of Being a Wallflower.” I remember its depiction of adolescent loneliness, the non-linear mental health trajectory that Charlie experiences over his first year of high school, and its scenes involving the Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Upon longer recollection, yes, the novel “Perks of Being a Wallflower” contains sex, which may have led to its ban.

The first reference I recall is the letter Charlie writes when he first learns about masturbation, or when a major plot point reveals that Charlie’s aunt sexually abused him as a child.

It’s then that I remember perhaps the most condemning aspect of “The Perks of Being a Wallflower.” I think again, and I remember the queerness inherent to the “Rocky Horror Picture Show.”

I remember Charlie’s significant friendship with Patrick, the stepbrother of Charlie’s love interest. Not only is Patrick gay, but he tells Charlie about gay sex.

In an interview with The Daily Iowan, Loren Glass, a University of Iowa professor in the English department, highlighted the demographics included in the book ban.

“It’s such a hodgepodge of texts, both popular and high cultural,” Glass said. “I think it’s pretty heavy on writers of color and queer writers, but it really cast a very wide net.”

Glass said he is against book banning both as an educator and a teacher, highlighting his conversations with his kids about what they are reading and what is available to them to read.

“The people I feel most sympathy for are the teachers and the librarians and the people who have to deal with this on the ground, who I know have our kids’ best interests at heart and want to be able to teach them and have the texts that they want to be able to use,” Glass said.

He said he feels angered by this recent legislation in its mistrust of teachers and public education.

UI third-year student Amritha Selvarajaguru, studying creative writing and secondary English education, advocates for access to literature.

Selvarajaguru serves as co-president of the English Society student organization at the UI.

She highlighted an earlier English Society meeting where members wrote letters of protest to Reynolds and the Urbandale school district regarding the book bannings.

“If someone is trying to hide any sort of knowledge from you, it’s probably important knowledge, right?” Selvarajaguru said. “People who are looking to erase or change perceptions of history, or are trying to create power for themselves, can’t do it when there is open access to information.”

As a student studying education, she said a main question she poses to professors relates to book bans and how educators should approach them.

“I think that book bannings are not an issue that are going to go away in the next few years before we get into the classrooms, unfortunately,” she said.

Selvarajaguru said while she wants to teach students a well-rounded curriculum with both classic and contemporary literature, there’s the pressing question of where the line is drawn.

In terms of books containing sex, Selvarajaguru poses the issue of what qualifies as sex. Is it a teenager getting their first kiss? Is it menstrual health? Is it conversations of consent?

“I can’t teach about real-life events anymore out of the fear that I might get fired or blacklisted from the entire teaching career just because I want to teach ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’” she said. “It’s like we’re always walking on these terrifying eggshells when all we really want to do is give kids a good education.”

She said that while the rationale of protecting children from harmful materials in classrooms sounds great on the surface, looking into reasons prompts questions of what legislators are truly banning.

“You can’t say I want to protect the kids and also want to deprive them of knowledge,” Selvarajaguru said. “Those are two opposite sides of the spectrum.”

Selvarajaguru noted how children will learn about difficult topics and that they should learn about them in a space that is safe and controlled.

“It really is hypocritical, this idea of protecting the kid because it’s not for their protection. It’s for your own protection,” Selvarajaguru said.

Glass said talking about sex through the frame of literature can give children a more positive learning experience in navigating mature topics, rather than looking it up on the Internet.

“The Internet is not there to help us teach our kids,” Glass said. “That’s there for a dump of every possible kind of thing you can imagine.”

He said books containing sex, such as “Brave New World” and “1984,” were for a long time standards of the high school English curriculum, indicating a history of discussions around sex in literature in public schools.

“A lot of folks now are demanding that they don’t want to be made uncomfortable,” Glass said. “It’s hard for teachers because of course, we frequently do feel that teaching reading is to introduce students to new things that might make them uncomfortable.”

Glass said context of what students are reading in classes is important.

For example, he said first graders aren’t assigned “Ulysses” because they aren’t at the comprehension and development level to understand it.

“The legislature needs to understand that there are professionals who have already established this,” Glass said. “There are people who have spent their lives studying child development and appropriate levels of reading.”

Sam Helmick, who serves as the community and access services coordinator for the Iowa City Public Library, highlights the history and importance of libraries in the state of Iowa.

“Iowa has more public libraries per capita than any other state in the nation, and because before they were adopted nationally, the Library Bill of Rights were actually drafted in Des Moines in 1938,” Helmick said.

Helmick said they were homeschooled and grew up in an environment where censorship was encouraged including in the household library.

“I remember holding up paperback books to the light, trying to see what my grandparents had marked out in black,” they said.

Helmick said finding libraries was a major part of helping them reconcile ideas counter to perspectives they were brought in and or currently hold.

“I encountered new ideas and new arguments and new theories and new perspectives that I wish I had access to [during] my upbringing,” they said.

Helmick said their position at the library allows for continual learning.

“You have collection development policies that try to uphold representation of multiple perspectives and tries to mitigate any unintended favoritism or exclusion of ideas ...” they said.

Helmick said there’s a decades-old reconsideration process facilitated by the library board at the library where community members petition if they think something doesn’t belong.

“What’s been disappointing about what’s taking place in Iowa with the second-most library adverse bills in the nation currently is that we’re no longer trusting ourselves to do the good work,” Helmick said.