Willard ‘Sandy’ Boyd remembered as an icon at the UI

UI community members share their favorite memories of former UI president and law professor Willard “Sandy” Boyd.

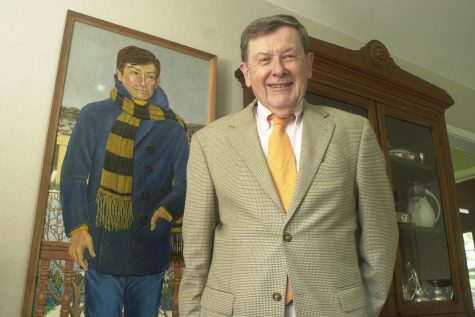

Former President of the University of Iowa Sandy Boyd reads from his memoir at the Iowa City Public Library on July 28, 2019. Boyd’s memoir is titled “A Life on the Middle West’s Never-Ending Frontier.”

When Steve Gude transferred to the University of Iowa in 1977 from Simpson University, he wrote a letter to then-UI President Willard “Sandy” Boyd during his first year. Based on his previous experience at a smaller liberal arts school, Gurden said he had suggestions about things he experienced at Simpson that the UI could consider for its College of Liberal Arts and Sciences curriculum.

What Gude didn’t expect was an invitation from Boyd’s office to meet with him.

“I really couldn’t believe it. I was just a nondescript undergraduate — one of thousands — who really didn’t stand out for any reason, and I was getting this chance offered to me,” Gude said. “That’s probably the thing that surprised me the most. He took the time to talk to somebody he’d never met before.”

Gude described his meeting with Boyd as taking place in an intimate setting. He remembered sitting across from the UI president, a coffee in both of their hands.

That day, Gude left Boyd’s office with a positive impression of the former UI president and a new respect for him.

“President Boyd could have just taken my written comments, replied with a thank you note, and left it at that, but he went the extra mile and met with me in person,” Gude said.

While Boyd was known for leading growth and change during his presidency, his character — such as being a good listener — also impacted the UI community and made him one of the university’s most iconic figures.

On Dec. 13, 2022, the UI community mourned the loss of a legend when Boyd died at 95 years old in Iowa City. But with his legacy, he’s left stories that inspire UI community members as well as a well-known quote: “People, not structures, make great universities.”

The Boyd Law Building is named in his honor, and the Larned A. Waterman Iowa Nonprofit resource center he created allows his legacy to live on at the university.

Boyd was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on March 29, 1927.

His dedication to public service lasted almost nine decades, over 65 of which were spent at the UI.

After practicing law for two years in Minneapolis, he started out as a university law faculty member in 1954 and was promoted to associate dean of the UI College of Law in 1964. The same year, he was named the UI’s 15th president.

Although people such as then-state Rep. Chuck Grassley were skeptical of Boyd’s appointment because he was perceived as too sympathetic to the interest of students, he led the UI through the campus’s growth and a rise in student enrollment from 1969-81.

Boyd believed that freedom and rights weren’t just for those who were the loudest and gave students with dissenting opinions the opportunity to be heard.

“Everyone on this campus deserves attention from the administration and faculty. The silent and vocal alike deserve our concern,” Boyd said in a 1969 DI article. “A person shouldn’t have to be vocal to be considered.”

During the ‘60s and early ‘70s, he navigated the university through the protests held in dissent of the Vietnam War.

Across the country, protests sent ripples across university campuses as demonstrations broke out, which in some cases turned violent, such as the Kent State Shooting. On May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guard members killed four students and injured nine others after firing into a crowd of demonstrators.

Although the UI didn’t experience any deaths or serious injuries like other campuses, it wasn’t immune to disturbances.

On May 6, 1970, the DI reported that 51 people were arrested during a demonstration against the Kent State Shooting. What started out as a protest escalated into a student and police confrontation after a firecracker and rock-throwing incident occurred in a men’s dormitory.

Boyd published a letter to the editor in the same print edition that called to preserve the UI community from violence.

“Sharing their frustration as I do, I understand the call for a class boycott as an effort to do something at a local level where individual students can make their concern known immediately. Accordingly, I believe we should regard May 6 as a personal conscience for all of us,” Boyd wrote.

Two days later, the DI reported an additional 250-350 demonstrators were arrested for sitting on the Old Capitol steps at 2 a.m. on May 8, 1970, after Boyd gave the order to clear the Pentacrest.

During a rally earlier in the evening, several people disturbed the protest’s peace by breaking into the Old Capitol building, breaking several windows, and smashing a painting.

As the UI community feared for their safety and violent threats loomed on campus, Boyd gave students the option to end their spring semester five days early.

“The University must represent the interests of all, no matter what their stand on the war. We cannot compromise on that issue,” Boyd wrote in the May 11, 1970, DI article.

But Boyd’s commitment to human rights and fairness didn’t just involve ensuring every UI community member felt heard, it also meant making sure the university welcomed all races, genders, and cultures.

Under Boyd’s leadership, the Afro-American Cultural Center was founded in 1968 during the civil rights movement as the first UI cultural center. Today, the Afro House provides Black students with a supportive and inclusive environment, programs to empower faculty and students, and the opportunity to share cultural knowledge.

Boyd also introduced greater diversity into UI leadership positions. He chose Phil Hubbard in 1971 as vice president of student services, making him the first Black vice president at the university and at a Big Ten school. Later, Boyd hired Mary Brodbeck as the first woman to hold the dean of faculties position at the UI; she would become the highest-ranking woman at a U.S. coeducational university at the time.

Adrien Wing, the associate dean for international and comparative law programs, said Boyd was “ahead of his time” and committed to diversity at the UI.

Timeline by Ryan Hansen/The Daily Iowan

An example of his dedication, Wing said, was when he served as the advisor for the Black Law Students Association, where he was well respected and beloved by the students.

“His commitment was not just can we bring diversity to the campus, but how do we make the campus or the law school inclusive, so that people will want to stay or have a good time while they’re at the university?” Wing said.

Wing was the first Black female professor at the law school when she joined the UI College of Law faculty and said Boyd served as a mentor in her role.

After his presidency ended in 1981, Boyd left the UI to become president of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

He returned to the UI in 1996 as a law professor and served as interim president from 2002-03.

“The law school became very diverse before he came back, and so, when he came back, he was very interested in what was happening, and in making sure that the diversity would continue to expand and be retained,” Wing said.

In 2020, the law school announced that 24.6 percent of the incoming class members were people of color, surpassing 1992’s previous high of 23.6 percent.

In addition, Boyd made a lasting impression on UI faculty members and students.

Paul Thelen, the director of the Larned A. Waterman Iowa Nonprofit resource center and an adjunct faculty member at the college of law, first met Boyd in 2005 as a student in his class when he was a professor in the UI College of Law during 2005-06.

If someone ever visited Boyd’s office, Thelen said they would have to understand that he never threw anything away.

When Thelen pictured Boyd in his office, he imagined Boyd sitting at his desk facing the window and looking outside with mountains of files and books surrounding him. Thelen said the piles of paper were a trait of his indelible memory — which are actions or memories that are impossible to forget.

But Boyd’s incredible memory wasn’t limited to what he read in law books or information from board agendas. Thelen said he made a point to remember people and care about them “as forever as forever can be.”

Thelen said he knew a graduate student who had a son and mentioned their son’s birthday to Boyd.

“And so, that came around the next year or whatever it was, and, you know, Sandy had wished her in the hallway, ‘Oh, happy birthday to your son.’”

When Thelen was a student of Boyd, he wanted to pursue the nonprofit sector like him and live by his quote: “It isn’t enough to do good, you have to do good well.”

“I was much more interested in the work that he was doing,” Thelen said. “How you go about being someone who makes communities better, and not just your community, but communities across in cities, and the entire state.”

Thelen said Boyd taught through experimental work with non-UI organizations. Through working directly with nonprofits, Thelen said he was able to learn the internal and external workings of organizations.

Today, Thelen leads courses Boyd once taught and incorporates similar pedagogical practices that Boyd used.

Beyond his memory, Thelen said Boyd was also a storyteller and a “fountain of knowledge.”

Josey Bathke, UI director of risk management insurance and loss prevention, taught a nonprofit organizational effectiveness class in 2010 with Boyd and said he held everyone’s attention for the entire two or three-hour class period.

“The way he could weave a story and hold your attention and just absolutely capture an entire classroom of students was just such a sight to behold because there I don’t see a lot of faculty members that have that ability,” Bathke said.

When Bathke co-taught with Boyd, she often asked him about his leadership experience and was impressed with his stories.

“After the physical class was over each week, I would sit with Sandy and ask him questions,” Bathke said. “I just loved that he had this amazing ability for storytelling. He could draw a picture with his words. Like, I would always ask him about when he was president in the ‘70s, and when there was student protests, and when there was turmoil, and how did he handle certain things.”

As the new UI director of employee and human relations at the time, Bathke told Boyd she didn’t think she would have time to teach.

But Bathke said Boyd was persuasive and contacted Kevin Ward, her boss whom he had known for decades, and Ward reassured her she would have enough time to teach with Boyd.

Beyond Boyd’s persuasiveness, Bathke said he was also always transparent, and he wasn’t afraid to talk to different groups of people to accomplish his goals, such as when he had to lobby the legislature to create the nonprofit center.

“He would tell the full story, not just the easy parts or the part that gets in the newspaper, but he talks about the hard work and research,” Bathke said. “And he truly believed in shared governance and listening to the different voices, the constituents on campus, whether it was the faculty or the staff.”

No matter his leadership position, one thing Thelen said stuck out most about Boyd was his ability to connect people to one another.

“He could go into different places, right, and meet different people and be able to pollinate and be able to kind of connect those folks and make abundance where there might not have been before,” Thelen said.