PolitiFact | The term ‘red wave’ is more complicated than you think

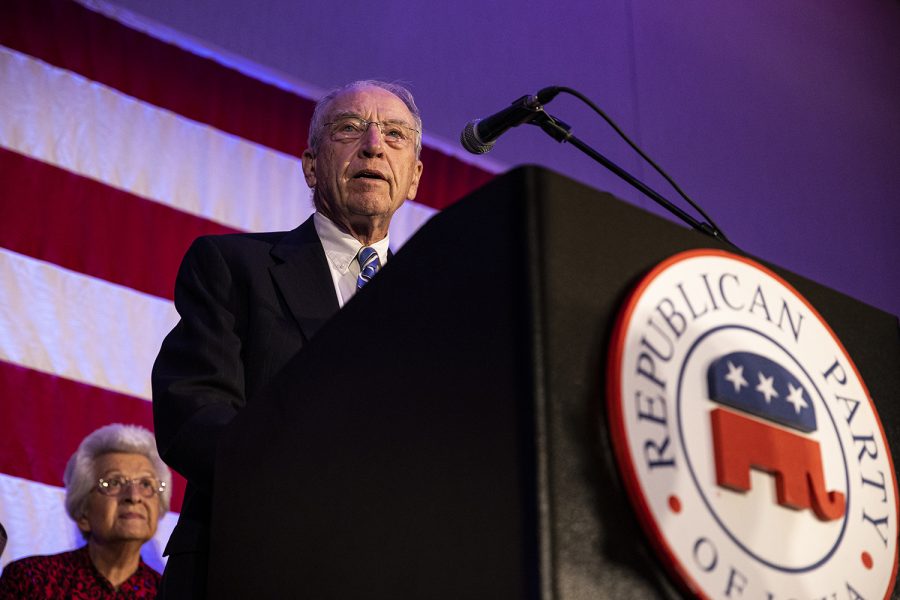

Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, speaks during a watch party for Iowa Republicans on Election Day at the Hilton Downtown in Des Moines on Tuesday, Nov. 8, 2022.

November 28, 2022

PolitiFact Iowa is a project of The Daily Iowan’s Ethics & Politics Initiative and PolitiFact to help you find the truth in politics.

If your time is short:

- Republicans at the national level predicted a red wave in the midterm elections this year but sustained losses in some areas they had hoped to win.

- In Iowa, it was a different story. Republicans deepened their hold on state government.

- Various political science experts say some criteria exist for declaring a red wave in elections but that the term “red wave” may not be as useful as news media relying on it portray it to be.

Despite predictions in some corners of a nationwide Republican surge in the midterm elections , Democrats made their own blue splash in some of the most hotly contested races on Nov. 8, keeping hold of the Senate while keeping Republicans from seizing as many House seats as they hoped.

The colorful terms “red wave,” along with “blue wave” in other years, get a lot of scrutiny, especially when a predicted wave doesn’t happen. So, PolitiFact Iowa and The Daily Iowan looked into how we can know if one of those waves happens, either nationally or in Iowa.

Generally, a red (or blue) wave refers to election results in which most of the intensely contested seats are won by the same party, especially in most parts of the country, according to academic research we reviewed and political scientists we interviewed.

Yet, agreement on the phrase’s usefulness in describing politics is not universal. Steffen Schmidt, Iowa State University political science professor emeritus, said the media love to use terms like red wave or tsunami with no specific background on what that term means.

“Some people are saying that ‘tsunami’ would have been better, which is, you know, a huge amount of water that rushes in and sweeps everything away,” Schmidt told PolitiFact Iowa. “I think ‘red wave’ was just made up as a kind of catchy phrase.”

Based on a combination of historical patterns and public opinion, some pundits predicted a national red wave would occur in this year’s election. In almost every midterm election since World War II, a president’s party has lost seats in the House, and has often lost them in the Senate. The losses tend to be especially large when the president has weak approval ratings, as Joe Biden did this year. (Here’s PolitiFact’s pre-election analysis of historical patterns in midterm elections and why 2022 might turn out differently.)

Ultimately, however, Democrats ended up winning many of the hardest-fought Senate races, including those in Arizona, Nevada, and Pennsylvania, enabling the party to keep its narrow control of the Senate. (One Democratic-held seat, in Georgia, remains to be determined in a runoff.) Democrats also prevented Republicans aligned with former President Donald Trump from winning key gubernatorial contests, and kept the number of seats flipped by Republicans in the House well below the more than 40 that changed hands in the most recent midterms, in 2018.

However, in some states, Republicans did exceed pre-election expectations. The GOP won commanding victories across the board in Florida, for instance, and they did much better than expected in U.S. House races in New York, despite it generally being a blue state.

One of the states in which Republicans cruised to victory was Iowa, where voters ousted Democrats in the state’s 3rd congressional district, state attorney general, and state treasurer. In the new year, only one Democrat will hold a statewide elected office, state Auditor Rob Sand, in a state that had three before the election.

In addition, Republican U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley kept his seat to enter his eighth term by beating Democrat Mike Franken, and Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds easily won her race for a second term against Democrat Deidre DeJear and Libertarian Rick Stewart.

In the Legislature, Republicans secured 22 of 34 Iowa Senate seats up for grabs. According to unofficial results, Republicans won 63 of the 100 Iowa House seats during the election.

Only five of 99 Iowa counties — Johnson, Linn, Black Hawk, Story and Polk — backed Franken over Grassley in the U.S. Senate race, Iowa Secretary of State data show.

Criteria and thresholds of the “wave”

There is no official definition of a wave (or a tsunami). But political analyst Stuart Rothenberg said in 2014 that a general wave, red or blue, happens when one party experiences a loss of nearly 20 U.S. House seats and the secondary party has few losses.

Matthew Green, a Catholic University professor of politics who wrote “Underdog Politics: The Minority Party in the U.S. House of Representatives,” reached the same conclusion for a 2018 Washington Post analysis of what was being called then a “blue wave.”

The GOP will fall well short of that figure; a few late-to-be-called contests will determine the final number.

The Political Dictionary’s definition of “wave election” says one happens when a political party makes significant gains in an election.

“Back in 2006, for example, nationally, the Democrats just wiped up, they won seats they weren’t expected to win,” said David Redlawsk, a University of Delaware political scientist who used to teach at the University of Iowa. “If you wanted to focus just on Iowa, you could say, yeah, they won most of the toss-ups,” he said.

“All of those are indicators of waves, and it’s very specific to the state.”

Redlawsk’s criteria for the red wave is not just about one side winning a lot. Rather, it is about all of the toss-up seats moving in the same direction, he told PolitiFact.

“You would sort of think that when let’s say there are a dozen races that are 50/50, could go either way, you would sort of think they’d be split half and half,” Redlawsk said. “But in fact, in a wave election, usually one party picks up nearly all of them. And, you know, we didn’t really see that.”

Tim Hagle, a University of Iowa political scientist, told The Daily Iowan that a specific number doesn’t need to be gained for the election to be considered a wave.

“One example of that could be how the Democrats had a wave election in 1974 after Watergate and gained 49 seats in the House, Hagle wrote in an email. “The elective offices usually refer to the U.S. House and Senate, but can include state offices (governorships, etc.) and state legislative offices,” he wrote.

“I think it’s clear there were really no waves in terms of this particular election,” Iowa State’s Schmidt said. “If we look at it nationally, obviously, individual states can differ.”

Our Sources

Iowa Secretary of State 2022 election results and county-by-county data

The Daily Iowan email exchange with Tim Hagle, Nov. 17, 2022

PolitiFact Iowa interview with David Redlawsk, Nov. 17, 2022

PolitiFact Iowa interview with Steffen Schmidt, Nov. 18, 2022

Rutgers Today, “What Happened to the Red Wave?” by Andrea Alexander, Nov. 9, 2022

PBS News, What the media got right and wrong covering the 2022 midterms, Nov. 13, 2022

Decision Desk HQ, Election Results, Nov. 18, 2022

New York Times, Live Iowa U.S. Senate Election Results, Nov. 18, 2022

Washington Post, “Was it a ‘blue wave’ or not? That depends on how you define a ‘wave,’” by Matthew Green, Nov. 13, 2018

The Atlantic, “The Real Metaphor of the ‘Blue Wave’,”By Megan Garber, Nov. 8, 2018

The History Channel, America 101: Why Red for Republicans and Blue for Democrats?, Nov. 3, 2016

About.com, What is a Wave Election?, by Tom Murse, July 13, 2014

Ballotpedia, “Media Definitions of a Wave Election”

Political Dictionary, Wave election definition, Nov. 22, 2022