Remaining unrecognized and unresearched has political, social, and physical health consequences

The Southwestern Asian, Arab, and North African community is growing dramatically in the U.S., yet many don’t even know we’re here.

Yasmina Sahir, a journalist who writes opinion pieces at The Daily Iowan poses for a portrait on Sunday, Feb 27, 2022 in front of the Starbucks on the corner of Clinton and Burlington in Iowa City.

March 1, 2022

As a Moroccan-American, I have heard the following about the state of Iowa from my white peers:

Racism and colorism doesn’t exist here.

Anyone can succeed if they try hard enough.

To answer, I can only speak from my own experience:

I recall being a fourth grader in a small town Iowa elementary school on Sept. 11, 2010. The boy sitting next to me — white, the child of rural farmers, and wearing one of his usual American flag shirts — raised his hand proudly.

“My dad says these people were stupid, and it’s good they died. Killing people because we wouldn’t follow their backwards ways,” he said.

There was silence in the room besides some chuckles from the student and his friends. The teacher’s face grew warm as her eyes met mine.

I was asked to leave the room and sit in the hall. We had moved on to our math lesson before I was allowed back into the room. Nothing about the incident was ever mentioned to me again.

This was the moment I knew: my culture and identity were wrong, shameful, and to be hidden.

When I grew a little older and a little wiser, I realized this was to be my educational experience — being asked to leave the room when others made the environment uncomfortable for me to coexist in.

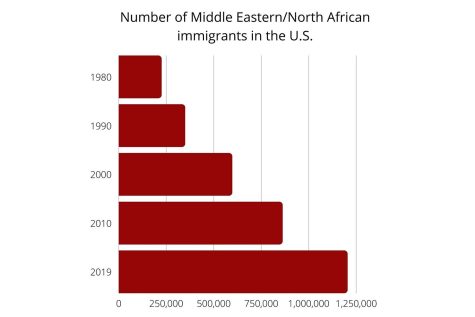

An LA Times article by Sarah Parvini and Ellis Simani, found that approximately 3 million Southwestern Asian, Arab, and North African — or SWANA — people lived in the U.S. as of 2019.

The U.S. Census Bureau reports the total U.S. population count is over 332 million people as of the 2020 census. This means that SWANA people make up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population.

This number is just an estimate, because SWANA identities are included under the “white” demographic category, as required by federal regulation. The same can be said for individual state population counts.

So, who exactly is a part of the SWANA community? This question has a complicated answer.

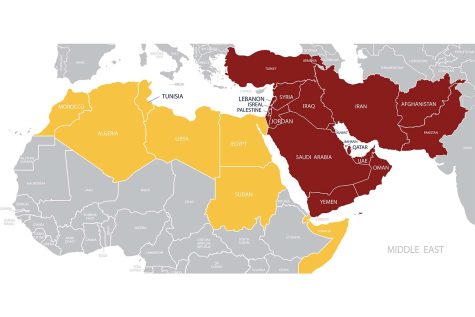

In a paper written for Johns Hopkins University in 2021, Nivine Zakhari explains that the SWANA “region straddles the African and Asian continents.” This has made it hard for governments to accurately label SWANA peoples, especially in countries that choose to define racial/ethnic categories based on geographic region.

“Identity formation for many of [SWANA] descent, relies on a complex historical view of race, ethnicity, national origin, and religion to situate one within the current social order, that rarely results in one simply identifying as White/Caucasian, Asian or African,” Zakhari writes.

Countries in the SWANA region include Iran, Turkey, Algeria, Morocco, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq, among others. The region of Southwestern Asian and North African countries was coined the Middle East during the height of colonization.

“The Middle East is a colonial invention ‘serving the West’s Eurocentric purpose’ to extend its sphere of influence through ‘civilising’ the Orient,” Yatana Yamahata writes in a thesis titled, “(Re)Shaping Territories to Identities: Is the Middle East a Colonial Invention?”

Of course, rhetoric changes are not always adopted by every person in a similar ethnic or cultural group. It is not uncommon to see the term Middle Eastern and North African, or MENA. The only wrong choice in this debate seems to be the exclusion of MENA/SWANA peoples to a white demographic category.

“[F]or young people, with 9/11 and now with Trump, whiteness means something specific,” said Khaled Beydoun, then a professor of law at the University of Arkansas, said in the same article from 2019.

Whether located in Iowa, the wider U.S., or on other continents, the MENA/SWANA community historically has and continues to experience specific health care needs distinct from those of other groups considered ethnically white.

These differences can be tied to ecoterrorism inflicted by Western nations in MENA/SWANA countries, various forms of stress, and generational trauma because of the War on Terror and colonization throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

According to the organization Intersectional Environmentalist, many countries in this region face sustainability concerns as a result of the forced removal of non-renewable resources and labor exploitation of women and children by companies based in the West.

In the U.S., Nadine Naber in the Chicago Reporter said that “[for] those [in the MENA/SWANA community] with high rates of college education, there is evidence that they are receiving lower expected returns for their years of education.” While Naber is unable to identify a direct cause of this, anti-Arab discrimination is considered a high probability.

When populations take on the debt to achieve education but do not see the same financial return when they enter the workforce, the result is extreme poverty that can impact the ability to accumulate generational wealth.

Concerns for this community go beyond civil-political and economic consequences of mislabeling.

According to Tori DeAngelis with the American Psychological Association, generational trauma describes when responses to trauma are passed down to or impact people indirectly affected by the original source of trauma. This “second-hand trauma” can stay in family lines for generations, impacting their collective mental health and achievement abilities.

Without racial/ethnic census recognition, theories about the disparities facing MENA/SWANA peoples are considered by some to be a moot point. Population counts lead to funding, and research cannot happen without funding. Similarly, resources cannot be distributed to seemingly “nonexistent” groups.

The above became too much of a reality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Deena Kishawi said in an article for New Lines Magazine, some COVID-19 hotspots are centrally located in areas majority occupied by MENA/SWANA communities.

Outside pandemic circumstances, other health care concerns — including genetic risks and lifestyle factors for the MENA/SWANA community — have gone largely unstudied as well.

“Many hail from politically unstable countries and, in recent years, many have endured some level of war trauma from events ‘back home,’” Kishawi wrote. “This, combined with a rise in Islamophobia and targeted hate crimes, may have physical and mental health ramifications on the community that remain unstudied.”

But that isn’t Iowa City. Iowa City is different, a haven compared to the rest of Iowa.

It is easy to look at national statistics and large societal trends and conclude, “but that wouldn’t happen where I live.”

When I moved out of the small town I grew up in, I was excited for the Iowa City promised to me: inclusive, collectively aware, and progressive.

Working at a local cafe in 2020 as one of the only people of color on staff at the time, my boss approached me, raving about how she had just attended a training on microaggressions. She felt so happy she was now enlightened about the plights of people of color.

This was the moment I knew: I could never escape the racialized ideas of the white folks around me. Even though I am considered legally “white,” descendants from Anglo-European groups don’t consider me their equals in daily interactions.

However, potential for positive reform in Iowa City does exist.

Various professionals have identified this group as distinctive from European-white groups.

Officially recognizing this would be a step toward obtaining funding for medical research.

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics is recognized as one the No. 1 hospitals in Iowa for 32 years running. Following funding allocation, UIHC has the capacity and academic rigor to be a central site for future research into MENA/SWANA-specific medical needs.

Demographic forms are not limited to hospitals but are seen in schools as well. Educational resources from elementary to college years — including scholarship funds, free and reduced lunch services, multicultural household recognition, etc. — could be more easily and equitably distributed with demographic reform.

Home to one of only 22 mosques in Iowa, there is room for education, understanding, and community building between MENA/SWANA Muslims and other religious groups.

MENA/SWANA peoples come in a variety of racial/ethnic identities, religions, socioeconomic classes, and citizenship backgrounds. Their experiences with colonization, war, ecoterrorism, and labor exploitation have resulted in wide reaching trauma that corresponds with experiences of other people of color and marginalized groups.