Opinion | The culture surrounding pre-health classes needs to change

The level of rigor in pre-health courses often does not match the teaching style, and instructors need to prioritize learning in these courses.

July 20, 2021

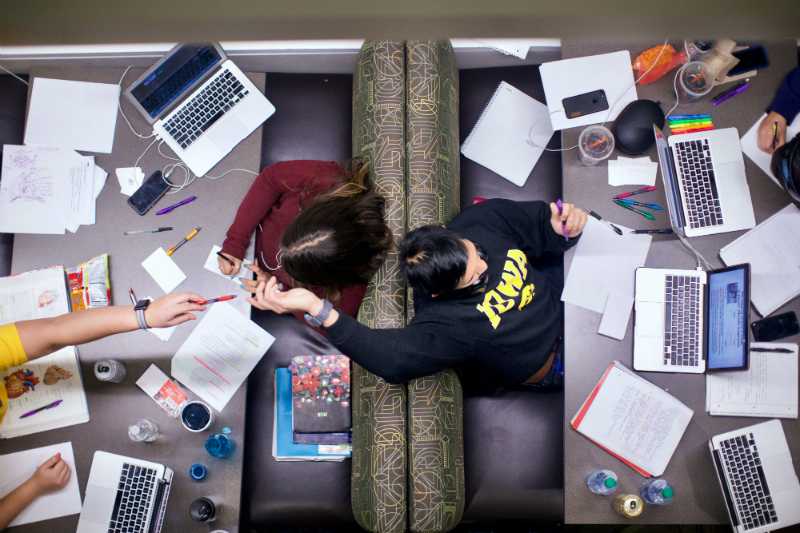

Most University of Iowa students taking pre-health and STEM classes have fallen victim to multiple weed-out courses. Instead of fostering an environment where students can learn and grow their passions in the sciences, they are expected to absorb a large amount of material with little guidance when it comes to testing.

Weed-out courses are rigorous classes where the instructors aim to discourage students from pursuing careers in those subjects with large amounts of work and harsh testing styles.

While offering rigorous and challenging courses is understandable for pre-health students, it can be extremely difficult to learn in these classroom settings. Instead, uplifting students and encouraging further inquiry in the sciences these classes tend to cause stress and frustration.

Pre-health career classes generally include several lower level and higher level biology courses, principles of chemistry classes, organic chemistry, and more.

For students to pass in some of these classes, they rely on a heavy curve to keep them afloat. The majority of students should not be receiving failing grades on tests and have to rely on a curve or adjusted scoring to get passing grades.

A study done by the Journal of the Association of the American Medical Colleges taken of pre-med students showed 88 percent of the students surveyed were concerned about earning the necessary grades to attend medical school. A large part of that concern comes from the level of rigor and competitive nature of these classes.

The seemingly high stakes pre-med and other pre-health students face takes a toll on their mental health. Research taken of burnout in pre-med students displayed they face higher severity of depression and emotional exhaustion than students not taking pre-med courses.

Jordan Trost, a rising senior studying public health and minoring in environmental science on the pre-dental track at the UI, said in her experience, the rigor of testing did not match the course work and teaching.

“The tests were always five times more difficult than what we actually learned,” Trost said. “The test questions usually combined multiple concepts even though in class they never applied the material in that way. If you have bad testing anxiety, you are destined to do poorly.”

If the purpose of these classes is to learn, professors should prioritize preparing their students with ample materials, practice, and clear communication. Instead, many professors hand students unreasonably large amounts of material without proper guidance and preparation.

Trost added that she did not feel she was able to prepare for these courses with the materials provided by the instructors.

“Some professors had study guides and one or two review sessions but if you weren’t able to attend them there was nothing to replace that opportunity,” Trost said. “There were also professors who gave study guides but not the answers saying that would be unfair. It feels like if you don’t have the money and resources for tutoring or extra practice to succeed in these courses you’re screwed.”

Through these very rigorous and tiring courses many students are discouraged from pursuing their dream careers.

“Me and the majority of people I met in pre-health classes were always questioning if we were good enough or smart enough or if the struggle of these classes was worth it,” Trost said.

Oftentimes, these classes end up fostering very toxic and competitive environments with the grading style. Students do not have the time or extra resources needed to dedicate to these classes and cannot always rely on their peers for help.

Further, these weed-out classes have been found to disproportionately ostracize minority groups from pursuing STEM careers.

It is ironic so many classes push students away from pre-health careers when there is a projected shortage of physicians in the country. Recent research taken by the Association of American Medical Colleges estimates a shortage of 37,800 to 124,000 doctors by the year 2034.

If the majority of students are getting failing grades with their raw scores, clearly the teaching methods are not matching the testing. Instructors should restructure these courses so the testing and grading style matches the teaching, instead of inducing an unnecessary amount of stress in their students.

Columns reflect the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board, The Daily Iowan, or other organizations in which the author may be involved.