Opinion | The Derek Chauvin trial jury selection shows deeper flaws in US justice system

Though a trial is the first step toward justice in this case, public scrutiny of the jury selection process highlights another impediment to racial justice.

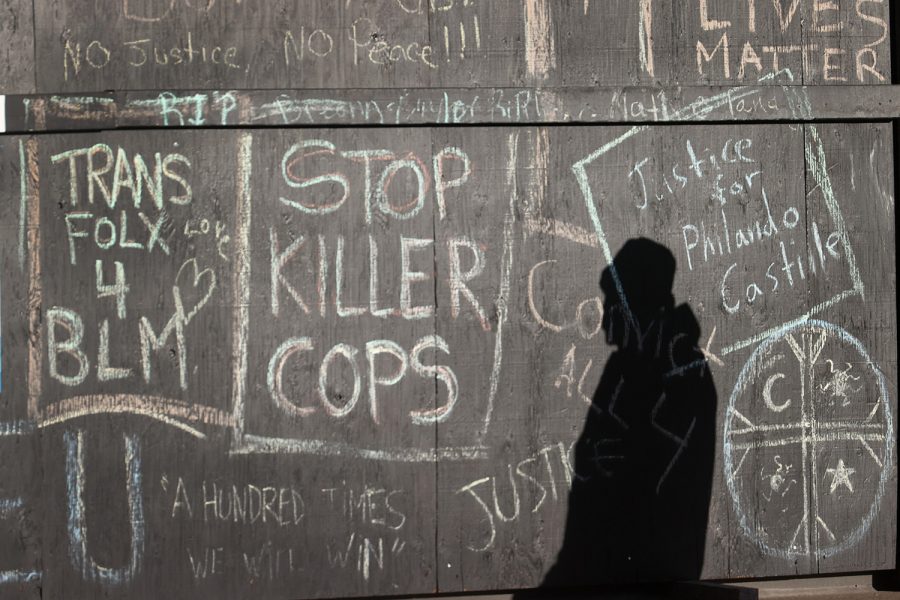

Pedestrians walk past a boarded-up building across from the Hennepin County Government Center during the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on March 31, 2021, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Chauvin is accused of murder in the death of George Floyd. Security is heightened in the city in an effort to prevent a repeat of rioting that occurred in Minneapolis and major cities around the world following Floyd's death on May 25, 2020. (Scott Olson/Getty Images/TNS)

March 31, 2021

The trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin — charged with second-degree murder, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter in the killing of George Floyd — began Monday. With the eyes of the country and the world turned toward the Minneapolis courtroom, many are questioning the manner in which the jury was selected.

The stakes of this case, which sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and racism, made the search for a jury all the more difficult yet all the more important.

This case presented particular difficulty in selecting a jury because of its high profile. Most jurors, just like most American citizens, have seen at least a portion of the widely publicized video of Floyd’s death or have some familiarity with the facts of the case.

Chief among public complaints was the 16-page screening questionnaire sent to potential jurors. Aside from gathering background information and asking respondents to relate their knowledge of the case, it asked questions like “Have you, or someone close to you, ever helped support or advocated in favor of or against police reform?”

The questionnaire also instructed respondents to list their level of agreement to statements such as “Blacks and other minorities do not receive equal treatment as whites in the criminal justice system.”

Questions like these are designed to help lawyers on each side identify which potential jurors would be sympathetic to their case and more likely to vote in their favor. Each side is allotted a number of jurors they can strike “without cause,” though the other side may challenge a strike if they believe it is motivated by a potential juror’s race, ethnicity, or sex.

Though these questions are routine, they may not lead to a more just outcome. Questions that gauge a potential juror’s opinions about the justice system, which has been shown in study after study to be biased against people of color, may be used as an excuse to intentionally strike minority jurors or may unintentionally lead to the same result.

The survey also asked potential jurors if they had ever been arrested for a crime, if they had ever personally seen police use more force than needed, and whether police in these instances acted professionally. Though relevant to the case, these questions further disadvantage people of color, particularly Black people, who tend to be over-policed and disproportionately affected by police violence.

The group selected for the Chauvin trial was made up of 12 jurors, two alternates, and a backup. Of these, four are Black, two are multi-racial, and nine are white.

But this jury’s makeup isn’t the issue, it’s the process by which they were chosen.

While the racial diversity of the jury might increase public confidence in the trial, the screening questions could have still prevented the jury from being a true representation of the defendant’s peers. If the questions are meant to exclude people who have had negative interactions with police, it leaves out people with valuable and relevant experience to the trial.

Questions about facts or jurors’ experiences are fundamentally different from questions of opinion. People can put aside their opinions for the sake of a trial. They can’t put aside their identities or deny the realities of the justice system.

The problem is that this is normal. Compiling a jury is always a tricky business and American courts have a long history of racial bias during selection.

We shouldn’t overlook this crucial aspect of justice in America. After Chauvin’s case is finished, perhaps it’s time we put our jury selection process on trial.

Columns reflect the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Editorial Board, The Daily Iowan, or other organizations in which the author may be involved.