Elizabeth Catlett: A life and legacy of art, activism, and academic achievement

Artists and university staff reflect on the legacy of Elizabeth Catlett. The artist spent decades creating art that showed her experience as a Black woman despite facing injustice along the way.

For many, the thought of meeting Elizabeth Catlett during her lifetime was akin to meeting a Hollywood A-lister. This was certainly the case for jazz composer Rufus Reid, who never thought he’d have the chance to meet Catlett, let alone be welcomed into her family.

In 2006, Reid composed a concert about Catlett and her work. The University of Connecticut was looking for submissions for an original jazz concert, so Reid applied by pitching Catlett’s art as his subject.

“I had a book about her and her art, and I looked at several paintings and sculptures of hers,” Reid said. “There were four sculptures that the photography was so good that they just popped off the page, and I said, ‘That’s it. That’s what I’m going to do.’ So, I proposed that I write music inspired by her, and I got selected.”

At the time, Reid didn’t know Catlett personally.

“I didn’t think I could just find her number in the telephone book, it was like trying to find the number of a movie star, so I didn’t even try,” Reid said. “Later I found out she has a son who lives here and that she had a place in lower Manhattan, listed right in the telephone book.”

The next time Catlett came to visit her son, Reid decided to reach out to him.

“The week she came to visit her son, I happened to be playing at a nightclub, and I asked her son if he thought she could stop by, and he said ‘Well, I don’t know, I’ll ask her,’” Reid said. “And she did; and that was the beginning.”

Catlett and Reid struck up a friendship shortly after. He said she was very down to earth and reminded him of his grandmother.

“I got welcomed into the family,” Reid said. “She invited me and my wife to spend a week with her in Cuernavaca. I didn’t respond right away, and she called and said, ‘Well aren’t you coming?’ So, we went, and it was fantastic.”

Catlett never ended up seeing Reid’s concert live, but they spent a holiday together. At the time, she was 92.

“To me, she was a national treasure,” Reid said. “Certainly not when she began her work at Iowa, but they saw talent, and she got better and better, and now she’s a world-class name.”

During her time at Iowa, Catlett studied with Grant Wood, a landscape artist most famous for American Gothic. Her roommate was poet Margaret Walker, who was involved in the Chicago Black Renaissance.

Before Catlett’s rise to fame alongside other notable Iowa alumni, she experienced what many other Black children of her time did — hearing stories of slavery directly from her grandmother.

Timeline by Chloe Peterson/The Daily Iowan

Catlett was born in Washington, D.C. in 1915, 50 years after the end of the Civil War, to the children of freed slaves. She and her two older siblings spent much of their childhoods with their grandmother while their mother worked as a truant officer. From a very young age, Catlett was made painfully aware of the horrors Black people in the U.S. faced just half a century before her birth.

It was also during her childhood when Catlett became interested in art, with a particular interest in sculpture making. In high school, she studied art with a descendent of abolitionist Fredrick Douglas.

After completing her undergraduate degree at Howard University, a historically Black university in D.C., Catlett struggled to find a post-graduate arts program that would admit her because of her skin color.

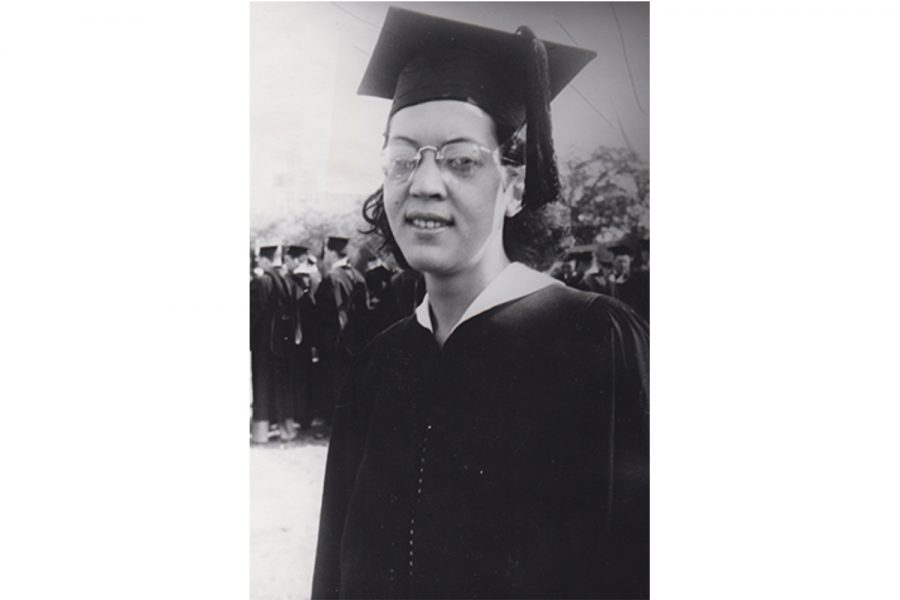

Although the University of Iowa wasn’t her first choice, it was the first university in the world to offer a Master of Fine Arts program, which Catlett was accepted into in 1940. She was in the first graduating class, making her the first African American and woman in the world to earn an MFA.

Chief Curator of Stanley Museum of Art Joyce Tsai said Catlett’s work spoke volumes.

“Elizabeth Catlett was an artist who held onto the human figure throughout her entire career,” Tsai said. “She was someone who was really committed to creating art that speaks to her own experience, but also provides artwork that her own community can draw strength from.”

Catlett’s works upset the status quo. After moving to Mexico in 1946, Catlett became involved with Taller de Gráfica Popular, an art collective that used its artistry to advance revolutionary social causes, including the Mexican Revolution.

Her prints also spoke to the Black Power movement, a movement in the ‘60s and ‘70s that advocated for Black pride and economic empowerment. It resulted in Catlett’s visa to return to the U.S. being revoked. She was unable to return while her mother was dying, and her citizenship wasn’t reinstated until 2002.

“There’s definitely a kind of critical edge to what Catlett does,” Tsai said. “There are several prints she does in support of Black power and Black militancy. But at the same time, we have to see these works in conversation with how motherhood can radicalize you to make this world a place where there’s not constant fear that your children will be targeted.”

Catlett died in 2012 at the age of 96. Following her death, she was celebrated as one of the most influential artists in history. Tsai said her legacy will live on because of the power it holds.

“The power of Catlett’s work lies in her capacity to capture the strength and dignity of Black experience with range, from images of Black power to quiet little vignettes of everyday life,” Tsai said.

Tsai said it’s fitting that seeing Catlett’s work around campus is now a part of everyday life.

“These buildings anchor us to history,” Tsai said. “I think it’s quite significant that her name is on a dorm that provides housing for students. African Americans weren’t allowed to live on campus while she went here.”

Assistant Vice President for Student Life and Senior Director of University Housing and Dining Von Stange said this was part of the reason a residence hall was named after her.

“In a sense, it kind of righted a wrong that the university had made 80 years ago,” Stange said.

Stange said Catlett’s name was the only one taken into serious consideration for the hall. Everyone involved in the decision unanimously agreed that Catlett deserved the honor.

“We wanted to recognize someone who represented Iowa and Iowan values,” he said. “She wasn’t a native Iowan, but she represents the diversity that the university wants to continue to develop.”