Third-party candidates lose ground amid high-stakes 2020 election

A close race and high stakes kept third-party platforms from gaining any traction in the 2020 election. However, while there are fewer third-party voters, the minor parties still hope to see growth.

November 10, 2020

Though 2020 election results are still being finalized, the percent of voters who voted for a third-party presidential candidate is already much lower this year than in 2016, largely because of the perceived high stakes of the election and slow growth of third-party platforms.

Third-party candidates got 8 percent of the total vote in Iowa in 2016, a number that went down to 2 percent in 2020. This isn’t unusual for a close race, Johnson County Democrat and political observer John Deeth said.

“In both 2000 and 2016, you saw the popular-vote loser win the election, and after an election like that voters tend to take the consequences of a third-party vote more seriously and are more inclined to cash a president-choosing vote rather than a protest vote,” Deeth said.

In 2016, the third-party margin was larger than the difference between President Trump and Hillary Clinton, and Deeth said people kept that in mind this year.

The Libertarian Party, with 19,586 votes, and The Green Party, 3,068 votes, had two of the highest vote counts for third-party presidential candidates in Iowa, with Kanye West falling between them at 3,203 votes statewide, according to the Iowa Secretary of State’s website.

Elizabeth Retikis, a fourth-year UI student, said she is a registered Libertarian but voted for Joe Biden and Sen. Joni Ernst in this election, saying she didn’t think Libertarian candidates could win.

“Statistically, Libertarians don’t win,” Retikis said. “While that is my party and I don’t align with Democrats or Republicans, I go on my gut based on the election.”

Mack Shelley, political-science department chair at Iowa State University, said third-party candidates have trouble gaining traction in major elections.

“If an election is seen to be relatively close in general, or seen as a life or death situation, those are circumstances that the third-party vote will be low,” Shelley said.

Shelley said there was a major independent campaign by Ross Perot, a billionaire industrialist who had the money to fund his own campaign, in 1992. Perot did well nationally, earning almost 19 percent of the vote. Theodore Roosevelt ran as a progressive party candidate and got 28 percent of the popular vote and 88 electoral votes in 1912.

So, while recent years show a decrease in third-party voting, the past has shown that these campaigns have not always gone unheard.

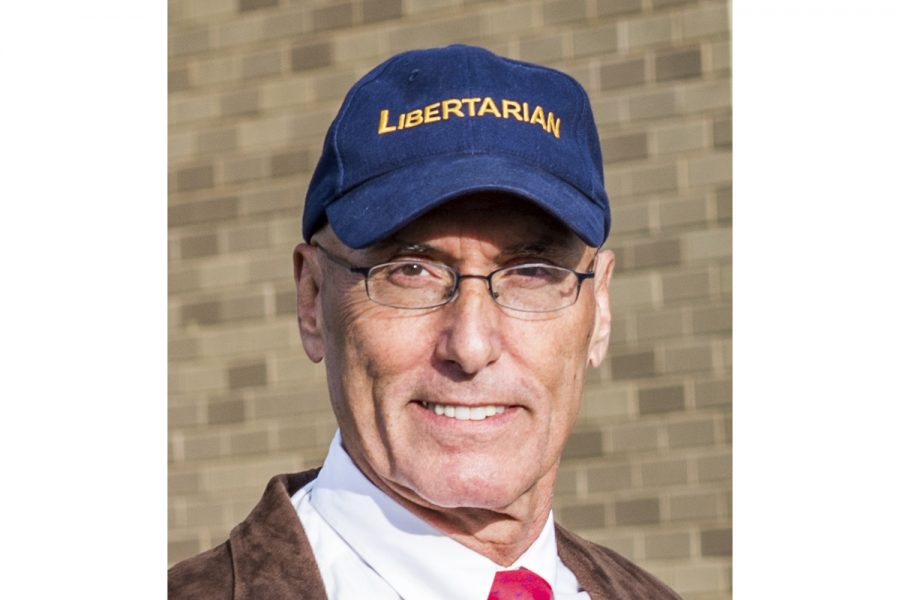

Rick Stewart, the Libertarian candidate for U.S. Senate in Iowa, said there is an increased interest in the Libertarian Party because people are growing tired of the two-party system, but people are not aware of the candidates and platforms of minor parties.

“I was the loser who did the best,” Stewart said. “I was the guy who spent less than $5,000 but got more votes than any other independents. I got 2.3 percent of the vote.”

Stewart received 36,897 votes, about 2.2 percent of the vote, in the 2020 election.

The first Libertarian to run for statewide office in Iowa was Ben Olsen in 1978, who received 0.45 percent of the vote. Stewart said that given enough time to grow, he thinks the party can be a major player in the races.

Because of how the electoral college is engineered, it is almost impossible for a third-party candidate to win. Shelley said it would need major fragmentation of the major parties, because of the winner-takes-all system.

“Hypothetically, if there was a serious third-party effort out of, like, California, and they won that state’s 55 electoral votes, that is a good start, because a western regional candidate can be quite recognizable,” Shelley said. “If anything, it can keep others from getting to 270.”

Deeth said the two-party majority system is the default, as long as the country carries on with the winner-takes-all system.

“Some states are experimenting with systems like ranked choice, but as long as Americans are taught to vote for the person, not the party, such reforms will have a hard time advancing,” Deeth said.

Stewart said the country is not well served by a two-party system, and it has reached its end game. The Libertarian Party, he said, can break up the Democrat and Republican duopoly by making the presidential debates open for other parties.

“The idea is corrupt and to keep anyone other than major parties out of the spotlight,” Stewart said. “It was figured out early on that they needed to hold onto the debates, to maintain that political power. If you can crack open the debates more voters would be more informed on varying parties.”