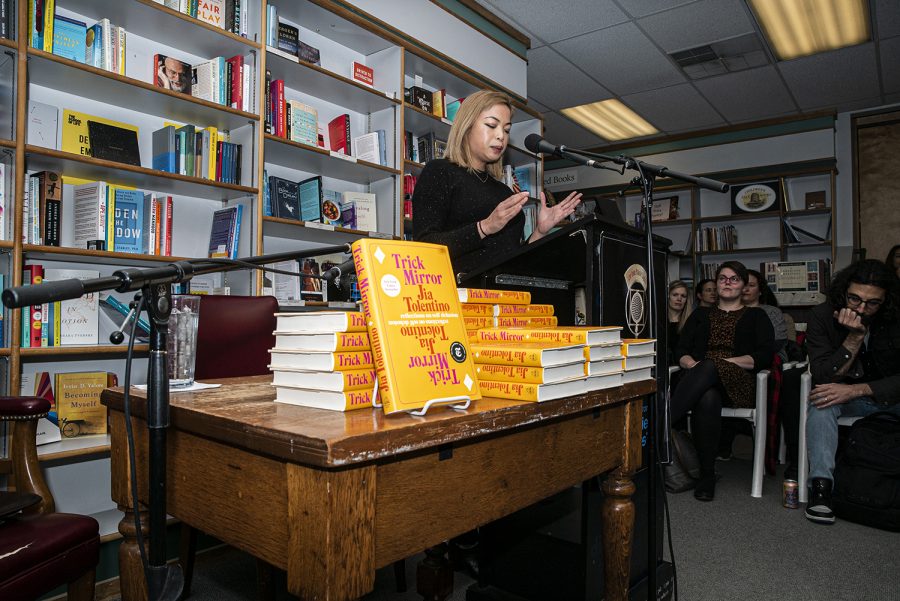

Author Jia Tolentino reads from her latest work, Trick Mirror, at Prairie Lights

Visiting Writer-in-Residence and The New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino shared her book of essays.

Brooklyn author, Jia Tolentino gives a reading at Prairie Lights from her book of essays, Trick Mirror on Tuesday, February 18th, 2020. Trick Mirror received rave reviews from publications such as The New York Times, The Guardian, and Vox.

February 19, 2020

The crowd at Prairie Lights Tuesday night sat ready to hear this year’s Magid Center for Undergraduate Writing’s visiting Writer-in-Residence, Jia Tolentino, who read from her latest book, Trick Mirror: Reflection on Self-Delusion.

Originally from Houston, Tolentino is a staff writer for The New Yorker. In 2019, her book of nine essays, Trick Mirror, was named New York Times Notable Book of the Year.

“This book and this incredible author have reinvented the [literary] eye,” said David Khalastchi, director of the Magid Center for Undergraduate Writing, after opening the reading.

Immediately, Tolentino dove into a half hour reading of an essay from her book that was also published in The New Yorker, Losing Religion and Finding Ecstasy in Houston.

Differing from many authors who visit Prairie Lights, Tolentino’s reading followed a unique pattern. Rather than reading little portions of her work at a time, Tolentino read her longest essay. She noted that all of the essays in the book were much longer than most other creative nonfiction essays recently released.

Despite its length, Tolentino read with ease and joy, laughing at her own writing at some points and capturing the audience further into her personal story.

Ecstasy itself captured something beautiful, yet odd. Her experience with God and drugs, specifically ecstasy, and her understanding of virtue and vice created a beautiful story of growing up, as well as an investigation of specific influential aspects of her story.

Many of Tolentino’s other essays contain research weaved throughout a personal narrative, although she said that Ecstasy did contain the largest use of personal narrative.

“I love to do research because the thing is, it’s like any thought that you’re thinking, someone has already thought it before and probably better, and that to me is a great comfort, because it’s like instead of trying to generate this… thought on my own, in a worse way, I can go to whoever said it better,” Tolentino said.

Tolentino said she came to writing late, believing that in college the extent of writing she would do would just be for grants for nonprofits. Before her time as a writer, she was an editor for Hairpin and Jezebel.

While writing is her current main line of work, Tolentino said it can often be like being trapped in a prison of her own mind. She said her work as an editor was incredibly fun, partially because of the ability to be free from her own mind.

“I found that … it was also such a fun way to learn things that I would never have known otherwise because these things would just come to you, and you would jump inside someone’s brain and their interests for a little bit,” Tolentino said.

Tolentino reminded aspiring writers of one of the most important things to get anywhere in the industry.

“There’s never [a] guarantee that anyone’s going to like [your writing], but if you have had a good time and gotten better that’s kind of all you can ask for and then maybe you get extremely lucky and things fall into place,” she said.