Julián Castro talks criminal justice at re-entry summit

At a summit with the Inside Out Re-entry Community, Former HUD Secretary Julián Castro touched on housing, employment, and policing when speaking about criminal justice.

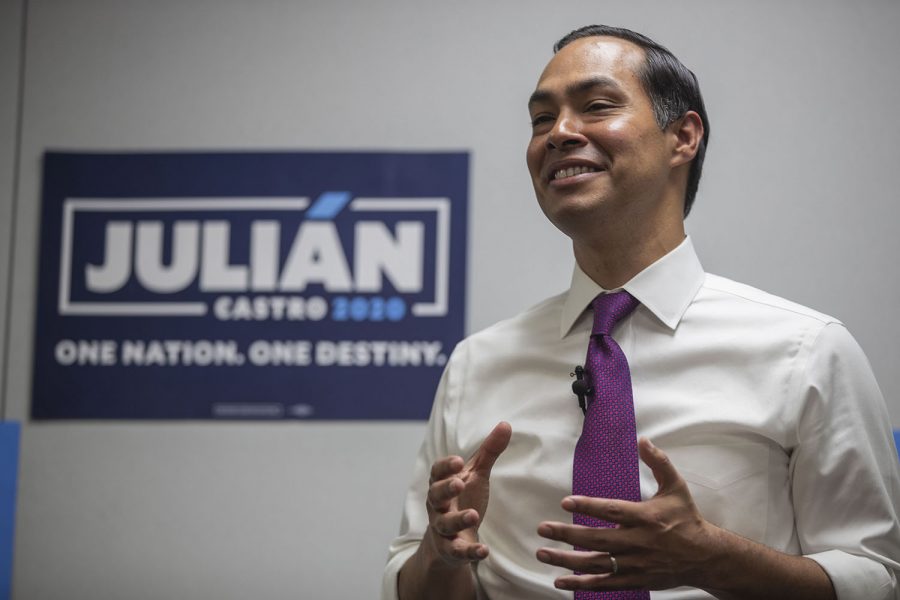

Former U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and 2020 Democratic candidate Julian Castro speaks on gun violence at a town hall organized by Moms Demand Action volunteers in North Liberty on Wednesday, August 14, 2019.

October 18, 2019

Former Housing and Urban Development secretary Julián Castro met with participants in the Inside Out Re-entry Community on Friday, a program that helps recently incarcerated people re-enter society.

According to the organization’s website, Inside Out offers a resource center where recently incarcerated people can get help with jobs and education, a mentoring program that pairs them with community members, and support meetings. Castro’s visit was part of a two-day summit Inside Out Re-entry was hosting on life after incarceration, highlighting the barriers people face to reintegration in society.

Castro spoke for a short time and spent the bulk of the hour answering questions from the about 20 people gathered in the audience at St. Andrew Presbyterian Church. Castro highlighted a number of issues that affected the life of recently incarcerated people, as well as the issues that affect incarceration rates.

Castro said a major piece of fixing the criminal-justice issues presented at the event was preventing people from being incarcerated in the first place.

“Too often times, the people that end up incarcerated don’t have an effective first chance in life,” he said.

Investing in K-12 education is a vital piece of keeping people out of prisons, Castro said. He also mentioned reforming drug laws and building on the First Step Act that was passed in December.

In an interview with The Daily Iowan after the event, Castro said police reform was a major piece of reforming the criminal-justice system. Castro has released a “People First Policing” plan, which aims to combat racial profiling and repair relationships between police officers and communities.

“My police reform tries to improve policing so that our communities are all safer, but also so less people who don’t belong in the criminal justice system don’t get entangled into it in the first place,” Castro said.

Many of the event’s attendees had spent time in prison, and spoke about the difficulty finding housing and employment after their release, asking Castro about a number of issues that affect barriers to re-entry.

Housing was a recurring theme of discussion, with many people expressing the difficulty of finding housing after leaving prison. Castro pointed to his experience as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under Barack Obama, saying cooperation between the government and the private housing sector is important to open more opportunities for felons to find housing.

“The challenge is, how do we work with that private housing market to make sure that they give people that second chance,” Castro said.

One measure Castro said would be helpful for both housing and employment is the “ban the box” campaign, which calls for the removal of the section on housing and job applications that asks if the applicant has a criminal record.

Michelle Heinz, the executive director of Inside Out Re-entry, said the ban the box campaign has been shown to improve an applicant’s likelihood of getting an interview, which in turn improves the likelihood of getting hired.

“Once you can sit next to someone face-to-face and explain the situation, you have a much better shot of getting the job than just a stack of applications that might end up in the trash,” she said.

To help improve employment prospects for people with a criminal record, Castro said he would expand tax credits for businesses and fund nonprofits and job-training programs.

Julie Redmond, now the operations manager at DES Employment Group, said finding a job was difficult when she was released from prison in 2007 after being incarcerated for eight years. She said she sat through 45 interviews before being hired as a dishwasher at a restaurant.

“There’s so many ‘no’s before you get that ‘yes’, before somebody takes that chance on you, and that’s the biggest thing,” she said.