UI study dives into new biotech that could replace needle-administered drugs

UI researchers are trying to understand how different skin-types react to the use of micropatch, a drug delivery method that is likely to grow globally.

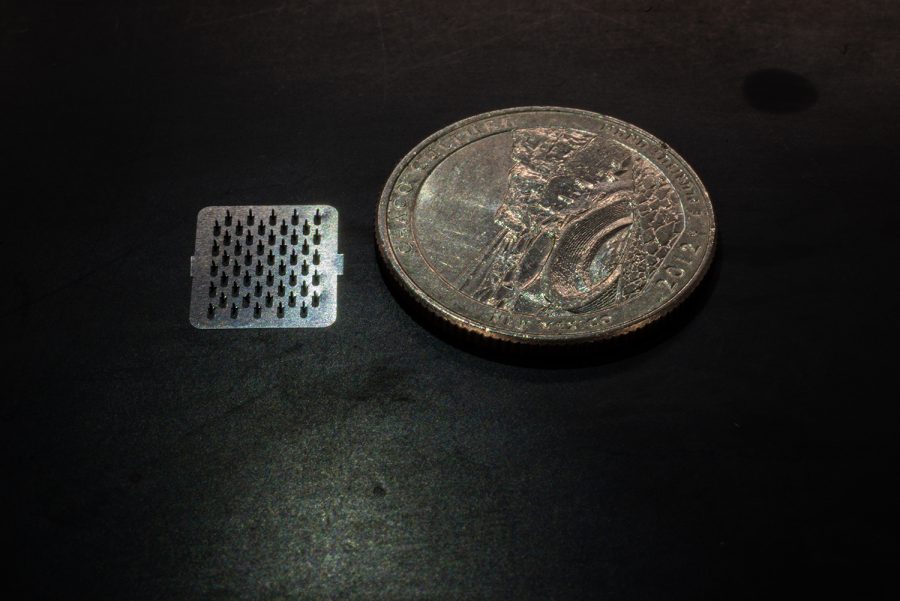

A metal micro patch is seen alongside a quarter at the University of Iowa Pharmacy building on Wednesday, December 5, 2018.

December 7, 2018

About as big as a fingernail, a micropatch is likely to be the future of injecting drugs.

A micropatch is a stainless steel array of numerous tiny needles used for drug delivery. University of Iowa researchers seek to understand how micropatches affect different populations to promote their use globally to people of different ethnicities.

“It can contain one [or] up to 1,000 needles depending on what the indication might be,” said Nicole Brogden, a UI assistant professor of pharmacy.

Most drugs are still delivered using a traditional hypodermic needle, she said.

“Most people dislike those, because they are painful, and there are a significant number of people in the population that have a needle phobia that is strong enough that they will not go to the doctor to get vaccines or things like that,” she said.

RELATED: Brain & behavior: Using stem cells to study psychiatric disease

Brogden said in the case of certain orally taken drugs, the body’s metabolism process removes a lot from the drug before the drug is used.

“So, we have to give much higher doses than the body actually needs in order to get the benefits of the drug,” she said.

Micropatches have tiny scalable projections that, when applied to skin, create a grid of tiny pores that are used for drug delivery, she said.

“There [are] very few drugs that can be delivered through the skin, and so what these allow us to do is we make these micros-scaled pores that allow us a portal for drug entry that wasn’t there before,” Brogden said.

A lot of research has been done to study how long the pores remain open in white people, she said. It is known that they remain open for about two days of good constant drug delivery.

RELATED: UI cystic-fibrosis research team awarded $11.5 million grant

“But people of color — we have never explicitly studied to see how long it takes for their skin to restore itself, and no one has really specifically studied if they have potentially different side effects than what we have seen at this point,” she said.

Looking into how different skin types react to the micropatch makes the research unique, she said.

“That is important, because if we are looking to use microneedles on a global market, we are not only focusing on white patients,” she said. “You are focusing on a global market that is going to encompass a variety of skin types, of different individuals that might react differently.”

The study looks into the closing mechanism in people of different races, said Abayomi Ogunjimi, a postdoctoral researcher who works with Brogden.

“Normally, after some time, micropores close,” he said. “We’re trying to look into how much time the skin closes in a Latino, an African, an African American, so this idea is going to help develop formulations to this needles [to] use it globally.”

As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, it is important that research studies have diverse participants so the study results can be generalized to the population as a whole, Nkanyezi Ferguson, a UI clinical assistant professor of dermatology, said in an email to The Daily Iowan.

“Micropatches have the potential to revolutionize drug delivery in the United States and the rest of the world, including developing countries that have large, diverse populations,” she said. “Minority representation in clinical trials and research can be low due to a number of factors, including lack of awareness that there is a need for participation of minorities in research and historic mistrust.”