Rosario: ‘Doctors said it was all in my head. I actually had dysautonomia.’

A DI columnist describes how she was dismissed by doctors before being diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.

Isabella Rosario sits in her apartment in Iowa City.

“This is not possible,” the nurse said, her face turning white as she read the pulse oximeter. “You are a healthy 19-year-old.”

My heart rate was 112 beats per minute lying down and 160 beats per minute standing up. A normal resting heart rate ranges from 60 to 100 beats per minute.

It was after this appointment in May that I was diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a form of dysautonomia, or autonomic nervous system disorder. Contrary to the nurse’s assessment, and those of countless medical professionals before her, I was not “a healthy 19-year-old.”

According to Dysautonomia International, POTS is estimated to affect 1 million to 3 million Americans, 80 to 85 percent of whom are women. This means the condition is as or more common than multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. But most people haven’t heard of the disorder, and doctors often fail to detect it.

I first got sick last fall, when I came down with a sore throat and the worst fatigue and muscle pain I had ever experienced. When I went to UI Student Health & Wellness, the doctor asked me a lot about my mental health. Like 1 in 5 U.S. adults who experience a serious mental illness within a given year, I have depression and anxiety. My physical symptoms, he said, were likely “psychosomatic” — i.e., caused by mental factors. I left with a pamphlet on depression.

Soon after, I went home and saw my primary-care doctor. Turns out, I actually had pneumonia. But even after taking antibiotics, I didn’t feel better — strangely, I felt much worse. I didn’t know why for months.

On some days, I was so lightheaded that I couldn’t get out of bed. I started taking the bus to class because my heart pounded when I walked. I had trouble concentrating enough to speak full sentences. I had constant headaches and body aches. My hands and feet turned purple and went numb when I wasn’t lying down. I made repeated trips to specialists and sometimes the emergency room, but nobody had definitive answers for me. Some doctors said I must be stressed from college, and surely my mental illnesses didn’t help. I couldn’t help but think all they saw was a hysterical young woman.

So, I did what patients are called hypochondriacs for doing: I consulted “Dr. Google.” I found POTS on the National Institutes of Health’s website and brought it to my doctor. She referred me to a cardiologist, who administered a tilt-table test and diagnosed me.

If I hadn’t done my own research, I would probably still be without answers.

RELATED: Rosario: Sexism stunts medical progress

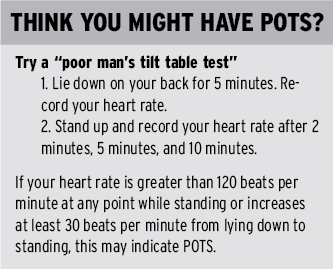

Like any form of dysautonomia, POTS is a breakdown of the autonomic nervous system’s involuntary functions. These include heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, and temperature control. All of these functions can be variably impaired in POTS. But the disorder’s main feature is a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute from lying down to standing up or a heart rate above 120 beats per minute within 10 minutes of standing. At my worst before being diagnosed, my heart rate peaked at 172 beats per minute while standing.

The biological mechanisms of POTS are poorly understood. Many patients have low blood volume and high norepinephrine levels, which activate an increased nervous system response. POTS has a range of possible causes, including autoimmune diseases and connective tissue disorders. My development of POTS was likely triggered by pneumonia, as infections are also thought to potentially cause autonomic dysregulation.

It’s not a coincidence that 80 to 85 percent of POTS patients are women and that they are routinely disbelieved. This reflex to tell women it’s ‘all in their heads’ — that their witness to their own bodies must be clouded by hysteria — is not exclusive to any illness.

Despite months of being dismissed, I was statistically lucky. The largest POTS survey to date found that patients can wait four years to be diagnosed. More than 75 percent of the 4,178 respondents were initially told their symptoms were psychological. Twenty-five percent said they were treated for a mental disorder before receiving an accurate diagnosis. Another study of 779 POTS patients in the UK had similar findings: 48 percent were told they were hypochondriacs.

It’s not a coincidence that 80 to 85 percent of POTS patients are women and that they are routinely disbelieved. This reflex to tell women it’s “all in their heads”— that their witness to their own bodies must be clouded by hysteria — is not exclusive to any illness.

Over the past year, I’ve heard disturbing accounts from friends who haven’t been taken seriously by medical professionals. One woman went to the doctor suspecting strep throat — which was later confirmed by another doctor — and left with a diet pamphlet. Another is hesitant to see a doctor for persistent leg pain because, in the past, she’s just been told to drink water and exercise.

My research for this article confirmed what I already knew to be true: women’s physical symptoms are regularly played down or assumed to be psychological. According to Academic Emergency Medicine, women with abdominal pain wait 16 minutes longer in emergency rooms than men. And they are seven times more likely to be sent home from the hospital during a heart attack, says research in The New England Journal of Medicine. A meta-analysis called “The Girl Who Cried Pain” found that women receive less pain medication, but more sedatives, than men; women’s pain is often perceived as anxiety.

The situation is even worse for black women and overweight women. A 2016 study from the University of Virginia found that half of white medical students believed at least one biological myth about black people: that they have thicker skin than white people or that their blood coagulates more quickly. Students who held these false beliefs recommended less accurate treatment. And a 2015 study from Obesity Reviews found that doctors spend less time with obese patients and fail to refer them for diagnostic testing. Instead, they suggest losing weight.

Doctors are well-intentioned people doing noble, invaluable work. But as people — regardless of gender — they are susceptible to the same unconscious biases that all of us are. As a society, we need to do better at trusting women’s accounts of their own bodies. Just because a physical illness isn’t immediately obvious doesn’t mean it’s a mental illness; a person can have both. If you are sick and feeling dismissed in doctor’s offices, please don’t stop standing up for yourself. You deserve to be heard. We all do.

Email: [email protected]

Katina Zentz is the Creative Director of The Daily Iowan. She is a senior at the University of Iowa and transferred from...