Joe Sharpnack headed to The Daily Iowan with a lifetime of political frustration culminating in the Reagan presidency, paired with a passion for drawing and storytelling.

He was raised on a ranch by the head editor of the Fort Collins Coloradan, toured briefly as a musician after high school, and came to the University of Iowa in his 20s to get a degree in English that he thought might help his spelling.

His mother had told him he came out of the womb sculpting the placenta, “and it just went on from there.”

“Now, if I couldn’t draw, I wouldn’t bother with this,” Sharpnack said. “If I couldn’t write or had no imagination, what’s the point? Then you’re just some Saturday morning cartoonist.”

Bolstered by the hope that his only flaw — spelling — would soon disappear, he began his career as a political cartoonist in Iowa City. The DI let him plaster his first cartoon across the school paper, a clear callout of Reagan’s Iran-Contra affair.

“Cartoons get people’s attention real quick,” Sharpnack said. “That’s the art of cartooning. Taking something that’s very complex and boiling it down to its most salient points.”

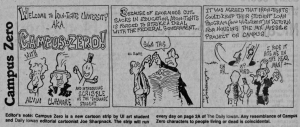

And he got the point across. He wrote regular strips with names such as “Campus Zero,” in which a “fictional” university traded the football field for funds so that Reagan had somewhere to build his missiles. Soon, the paper filled an entire page with angry Letters to the Editor about Sharpnack’s work.

The way he saw it, the hate mail meant his career had really begun.

“To get a page full of letters from somebody who had to put it on paper, put it an envelope, stick a stamp on it, and send it to the editor … you’ve got to be dedicated for that,” he said. “I got no problems engaging people with this stuff.”

Unfortunately, he said, a “suit,” a kid who went on to become exactly the “corporate schmooze” he came off as, became the head editor of the DI, and “Campus Zero” was out the door. It foreshadowed a trend in Sharpnack’s career: highs followed by systemic lows.

For each of Sharpnack’s personal victories, the world of journalism shifted just enough to jeopardize his career as a political cartoonist. Still, he battered at the barriers of his medium, proud to come from a newspaper family, dutiful to the role of the Fourth Estate as the watchdog on the government.

“It’s always the traditional media that get your stuff out there. Always,” Sharpnack said. “People are obsessed with this stupid idea that ‘Oh, I’ll put something really good on YouTube, and it’ll go viral.’ And a lot of that stuff has — but what became of it?”

While he was in college, still at the DI, Sharpnack was syndicated by The Washington Post. He paid about $15 in postage each week to be published, getting a little less than $1 in return, along with the captive attention of the entire nation.

“If I make enough money to live, I’m OK,” Sharpnack said. “The most important thing is to get the message out there.”

Chicago’s Daily Southtown gave him his first postgraduate job, one of only three full-time staff positions he has held. He met his best friend, kept writing for the Post, and received a Lisagor Award, which he described as the “Pulitzer of Chicago.”

When he was sick of the city, he returned to Iowa and was able to use his industry knowledge and thick skin to maintain close to 40 freelance contracts with papers in different cities across the country.

He considers the late-90s the peak of his career. Not only did his cartoons take off, he landed a contract to produce flipbooks and published the anthology Attack of the Political Cartoonist, which put him on a national book tour that began at Prairie Lights and featured a line of people out the door.

For approximately 20 years, he made a living as a political cartoonist, which is about the best a cartoonist can hope for.

“I was proud of the fact that I could pull it off for this long,” he said. “I mean, that is some scrambling every day.”

Scrambling was the best he could do in the world of print newspaper, which, he said, was fueled by corporate advertisements and readers who attacked his work as often as they commended it.

When his 10-year staff position at the Cedar Rapids Gazette ended, it was the final straw.

“He kept using these euphemisms for getting canned,” Sharpnack said. “I’d say, ‘Money, right?’ and he’d say, ‘Reallocation of resources’ … it was like, you’re talking to a cartoonist here, you think I’m going to go for this hogwash, whitewash crap?”

After weeks of unemployment that turned into months, dissatisfaction that grew in to debt, Sharpnack took an opportunity to teach English in third- through sixth-grade classrooms in South Korea.

“I saw the Arctic Circle, saw the curve of the Earth, my God,” he said. “I went to Korea, and I taught there for over a year.”

He put cartoons up on the board and taught panel by panel, applying his skills in a way he’d never considered before. It felt good. But he wasn’t ready to trade his freelance career for teaching, so he headed home to pursue new opportunities in voice acting without violating his work visa.

Sharpnack’s voice, rather than his drawings, brought another peak in his career. Along with pursuing voice acting, he returned to his passion for music and joined Iowa’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014 with a band assuredly as entertaining as the name promises: Oink Henderson and the Squealers.

Three years later, though, it’s not the sound of the music that makes Sharpnack reminisce, makes his eyes drift off. An incredibly rare condition has diminished his vision to 26.2 percent of what it was. He sees massive blockages, blackness, and around them everything appears as if underwater. He misses his eyes.

“It’s something that happens overnight,” he said. “I mean, you do not see this coming. It’s not like, ‘Joe, if you just lay off the hot dogs, your eyes will be fine.’ It’s like, boom … what a perfect irony for a cartoonist, right.”

“So, I became Guinea Pig Number 6G4. I’ll probably be in a journal somewhere, Guinea Pig 6G4.”

He misses the rhythm of words, which he loses reading them one at a time. He developed a love for literature as an English major, and even as a cartoonist, most of his job was spent reading, educating himself on the issues of the time. These days, Sharpnack listens to the news.

But his blindness seems less like irony and more like metaphor. He is not a guinea pig but an oracle, bringing bad news about what he has seen journalism becoming.

“Cable and radio are basically headlines,” he said. “There’s no in-depth reporting on anything … it’s shallow. There’s nothing there.”

Looking for hope in today’s political arena seems to be a scramble for Sharpnack, the way his whole career was. But as always, he holds out the hope he needs to keep going, bringing some dark humor along the way.

“As long as the message is out there, the medium doesn’t really matter, as long as you’re doing good journalism,” he said. “It’s changing, and I think it’s going to find its way.

“Either that, or we just saw the last election, and everything else will be a propaganda point.”