“No pain, no gain” is often a phrase used among athletes to push through tough training to improve their performance.

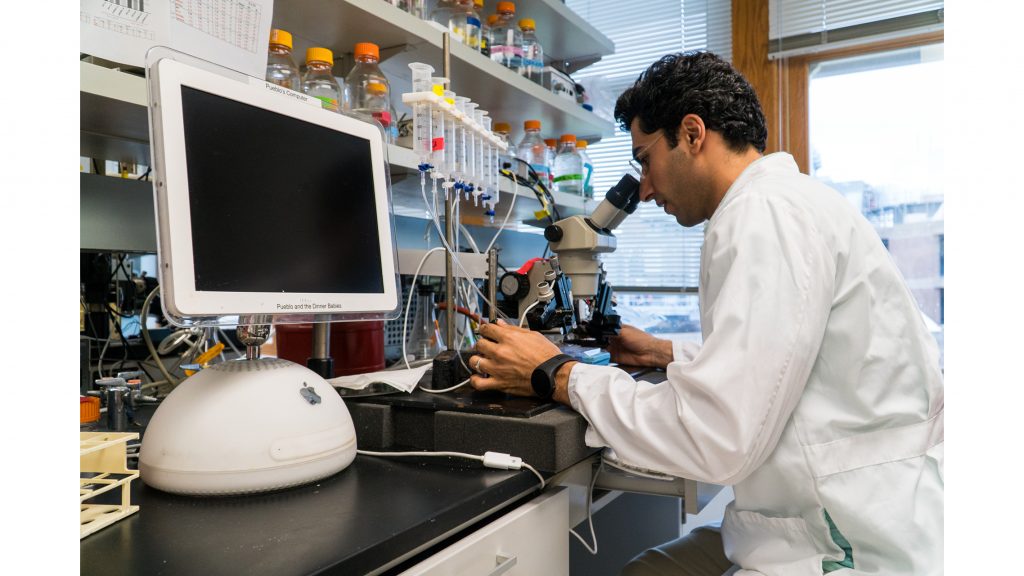

Tahsin Khataei, a research assistant in the Benson Laboratory of Internal Medicine, is quite familiar with this; he trained high-performance athletes in his home country of Iran.

The “pain” in his conditioning refers to high-intensity, interval-training, a style that has become widely popular because its efficiency both in training and in time. Examples are two- to 10-minute interval sports such as rowing, 800-meter runs, wrestling, and judo.

Khataei was inspired to understand the connection between high-intensity interval training and pain reduction in mice — affecting both high-performance athletes and a variety of patients with chronic pain.

He has delved into acid-sensing ion channels in skeletal muscle that connect to sensory neurons and how they affect pain.

“Ion channels are proteins in the membrane of cells that can be activated to open and close in different ways and cause a change in sodium, calcium, etc.,” Khataei said. “As the name implies, acid-sensing ion channels are sensitive to acid in muscle and are activated in acidic conditions such as hypoxia, inflammation, etc., and are located in sensory pathways.”

During strenuous high-intensity interval training, muscles release lactic acid, causing the activation of acid-sensing ion channels — where the peripheral nervous system gives feedback to the central nervous system that there is a sensation of pain.

“Exercise induces pain through high lactic acid … causing a barrier for high-performance athletes to perform at their highest level,” Khataei said. “It is an unpleasant experience because of pain and fatigue in muscles.”

So then, the question arises, how can causing pain through high-intensity interval training result in pain reduction?

“We trained mice for a minimum of four weeks with [high-intensity interval training] performed every other day, and we found that the [genes] for the acid-sensing ion channels were reduced,” Khataei said.

Finding reduced genes for these ion channels implies that they are no longer present, are used less, and less pain is perceived.

To confirm this connection, the lab studied pain perception in mice who performed high-intensity interval training for eight weeks. Findings showed a longer reflex time to pain stimuli.

“The longer the time means the less pain the mice feel,” he said. “So we learned from this that [high-intensity interval training] modulates pain.”

With pain perception decreased and athletic performance increased, there is an adaptation of the sensory nervous system to high-intensity interval training conditioning.

“High-performance athletes can feel pain in higher thresholds and tolerate it for longer periods of time,” Khataei said.

He finds that this “painful” high-intensity interval training is a temporary sacrifice of comfort that when endured gives long-term rewarding results for training coaches and their athletes.

Khataei’s study also has implications that go beyond athletic performance.

“[High-intensity interval training] can benefit those with chronic pain such as neuropathy, fibromyalgia in a non-pharmaceutical, non-opiate treatment,” he said.

While the results of this type of conditioning is very promising, Khataei cautions that it must be done with supervision and the use of high-intensity interval-training experts.