As the Iowa Legislature prepares to wrap up this session, one bill has been stymied on its way to the governor’s desk. Health officials said the bill would have put one more tool in Iowa’s inventory to prevent an HIV outbreak and combat the rising number of hepatitis-C cases and a nationwide opioid epidemic.

The bill would have legalized needle exchanges. Already legalized in 19 states, the programs allow intravenous drug users to dispose of used needles and receive clean needles for free.

Once legalized, the move accompanies services already provided by organizations such as eastern Iowa’s Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition, whose leaders played a significant role in bringing the legislation to the Capitol.

However, advocates will likely need to wait another year to see a legalized exchange program.

“I hate to say it, but it looks like the needle-exchange bill is probably dead for this session,” Sen. Tom Greene, R-Burlington, said. “I am fully in favor of a legal exchange program, but I don’t think it will be moving through the Legislature this year.”

The harm-reduction coalition, founded in December 2016 by University of Iowa medical student Sarah Ziegenhorn, provides outreach services for people who inject drugs and has begun the initial groundwork for a needle-exchange program if the Legislature were to give the OK.

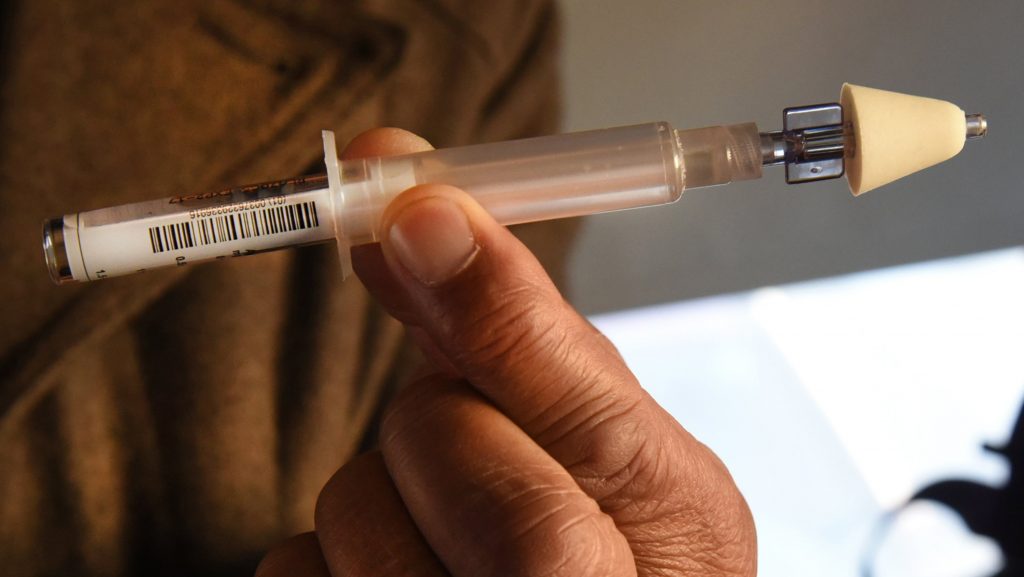

Each weekend, volunteers travel to either mobile or stationed outreach sites in Iowa City, Cedar Rapids, and Des Moines, where volunteers distribute condoms, Naloxone, HIV and hepatitis-C testing, resources related to community treatment and housing programs, and safer injection supplies such as cotton, alcohol wipes, and sterile water. Basically, everything except needles and syringes.

The coalition is the largest provider in Iowa of Naloxone, a medication designed to reverse opioid overdoses. Ziegenhorn said volunteers have tallied 101 reported cases of clients who have used it for overdose reversals since June.

After growing up in Iowa, Ziegenhorn worked in Washington as a public-health-policy analyst for a think tank during the day. By night, she volunteered for a harm-reduction organization and syringe-exchange program, which is legal in D.C.

When she moved back to Iowa in 2015, she said, she found herself in a place with limited harm-reduction policies and programs, prompting her to create the coalition. She said she sometimes works for as long as 90 hours a week going to outreach locations, organizing supplies, and building relationships with clients.

“It was mostly disappointing that this type of work was not happening in Iowa, and I wanted to continue to be engaged in that type of work,” Ziegenhorn said.

Such work would be expanded by a legal needle-exchange program.

Under current law, possession of drug paraphernalia, including hypodermic needles and syringes, manufactured or used for an “unlawful purpose,” is a simple misdemeanor that can result in a fine from $65 to $625 and a sentence of up to 30 days in jail.

The proposed bill would have clarified “lawful purpose” to include needles distributed by an approved needle-exchange program.

Although there is always a small chance for a last-minute amendment to be passed in other bills, legislators are setting their sights for renewed work next year.

“I have a bill today that passed after I’d been working on it for three years. You’re going to have to educate people,” said Sen. Kevin Kinney, D-Oxford, a member of the Opioid Epidemic Evaluation Study Committee.

Syringes and needles can be legally purchased at pharmacies without a prescription. However, some pharmaceutical providers, such as CVS, require a proof of prescription for purposes including insulin injection for diabetes.

The bill was introduced in February 2017. Ziegenhorn said that at one point this session, she and her advocacy team received commitments of support for the bill from 44 of the 49 Iowa senators.

Despite widespread support, the bill was never brought to a vote in the Senate; it didn’t make it out of a committee in the House in time to survive two funnel deadlines, the legislative rules put in place to weed bills out of the House and Senate.

A letter from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention sent in November 2017 determined that Iowa was in need of needle-exchange programs to prevent a future HIV outbreak.

Hepatitis-C cases in people under the age of 30 have more than tripled in the last seven years, according to a fact sheet from the Iowa Public Health Department, and it’s partially because of the increasing use of injectable drugs.

Ziegenhorn said those who oppose the Legislation think needle-exchange programs condone and support drug use. However, according to the CDC, people who participate in syringe-service programs are 5 times more likely to go into treatment and are more likely to reduce or stop injecting.

Kinney said he had hoped the measure would have been included in another bill that would require prescribers of opioids to register with a monitoring program. That bill passed the Iowa House on Feb. 26 and awaits passage by the Senate before it can be signed into law by Gov. Kim Reynolds.

In January, at the start of the legislative session, the Iowa Public Health Department published a checklist of ways to combat the opioid crisis in the state as a part of an updated report. Legislative liaison for the Public Health Department Deborah Thompson said in collaboration with the CDC, the state agency listed 10 policies as a to-do checklist that have worked in other states. Thompson said that while the current opioid bill being considered checks off seven boxes, sustainable syringe and needle exchange was one item left unchecked.

She said, however, the Public Health Department was neutral on needle-exchange legislation.

Currently, there are 10 public-health centers run by the state agency whose services would be well-suited to house the needle-exchange programs, Thompson said.

And it wouldn’t cost the state any extra funding. According to a March update from Public Health, federal funds already appropriated to the centers for HIV and hepatitis-C services would also pay for staff and supplies of a syringe-exchange program.

“What we would benefit from is the close relationships those people have with the at-risk population we are trying to target,” Thompson said. “[Syringe-service programs] add value to their offering; just like any business, it would be an additional value service that would attract people to their facility.”