When Craig Just arrived in Goodell, Iowa, with other professors on the University of Iowa Faculty Engagement Tour in 2010, he was met by a mob.

The people wanted to know why they had just been hit with a $2.1 million wastewater-treatment-facility bill.

“We got an earful there,” he said. “Over 100 people showed up; mayors from about four or five different towns came to that meeting. [The towns were] going bankrupt over this.”

The problem? Old wastewater-treatment lagoons had left more ammonia and bacteria in the water than new regulations would allow, said Just, a UI assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering.

Seven years later, it is still an issue. Larry Bryant, the Iowa Department for Natural Resources wastewater-technology coordinator, said that although 70 percent of Iowa’s wastewater facilities are lagoons, they hold only about 10 percent of Iowa’s total wastewater. These small, rural facilities struggle to keep up with environmental regulations that cities such as Des Moines have no problem handling.

“The natural systems do a good job,” Bryant said. “But they don’t necessarily convert ammonia to nitrate very well during cold weather.”

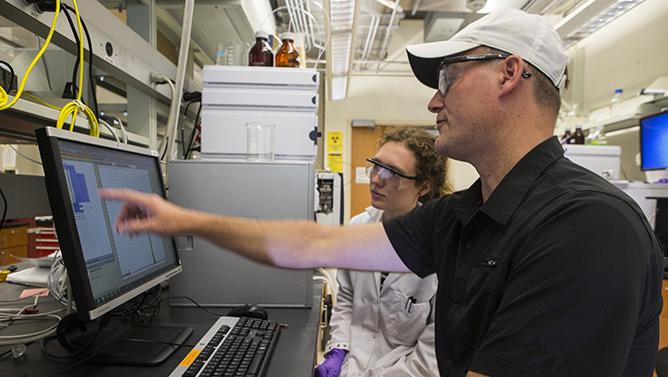

Just and research assistant Rebecca Mattson, a UI graduate student studying environmental engineering, are looking for ways to mitigate the cost of upgrades while protecting Iowans’ health and the environment year-round.

They are working at an “alternative wastewater treatment system” in Walker, Iowa, that “fits in the footprint of one their existing lagoons,” Just said. Three smaller lagoons are aerated to help convert ammonia to nitrate, and the wastewater then flows through “rocks in a box” that catch the bacteria, he said.

Mattson collects samples of microbes, water chemistry, and DNA in order to try to determine how Walker can pump in less oxygen and save money without losing effectiveness. Additionally, less oxygen means less nitrate, which can cause algae blooms and dead zones if left in the water.

Mattson said working with Just on wastewater treatment combines “all of things I wanted to do together into one field.” After graduating from the University of Minnesota, she came to the UI to get a master’s degree because of Just.

“We had a really good conversation about trying to help different communities in Iowa as well as abroad,” she said.

Mattson and Just will head to Nicaragua next week with Engineers without Borders to assess a community’s 30-year-old water-distribution system. Its current infrastructure is falling apart and does not treat the water, resulting in large outbreaks of E.coli, Mattson said. The engineers will work with the community to see if they can design an improved system that will meet the needs and means of the people.

“Anybody can engineer stuff if you’ve got a bunch of cash,” Just said. “Can you engineer stuff for a community that doesn’t have very much stuff? Where you maybe don’t even speak the same language, whether that be physical language or cultural?”

That is where engineering makes the most impact, he said.