By Helaina Thompson

A cup of hot tea sits in my palms. This is my second visit to India, and I’ve answered this question many times. “Our organization serves the elderly and the critically ill, those who have been abandoned by their families,” I say. “We give them medicine for their pain. We provide social support. Many of our patients don’t even have someone to talk to.”

My friend’s father, whose cups we are sipping from, responds, “Is it not the same where you are from?”

* * * * * *

Filmmaker Danny Boyle took me on my first trip to India. As a teen, I watched one of Boyle’s breakout films, Slumdog Millionaire, regularly from the comfort of my childhood home. I was mesmerized by its jarring footage of Indian slums, imagery that many critics would later scorn for its worn-out stereotypes and “poverty porn.”

In December 2015, seven years after the film’s release, I visited southern India as a student on the University of Iowa’s India Winterim program, which over the past 10 years has sent more than 1,000 students to cities across India. In November 2016, I returned for a second time to complete a multimedia project. Twice I traveled in the name of “voluntourism,” a growing trend in the tourism industry that combines international travel with volunteering efforts, most often in poor regions of Asia, Africa, and South America.

Roaming India’s busy streets, I clutched my purse to my body. I hesitated to respectfully leave my shoes unaccounted for outside of Hindu temples, looping the heels through my fingers and carrying them with me inside. I followed the rules the West had taught me about visiting a so-called “developing country”: my role here was to help, to provide — but to outsmart those I was told would take advantage of this Westerner.

* * * * * *

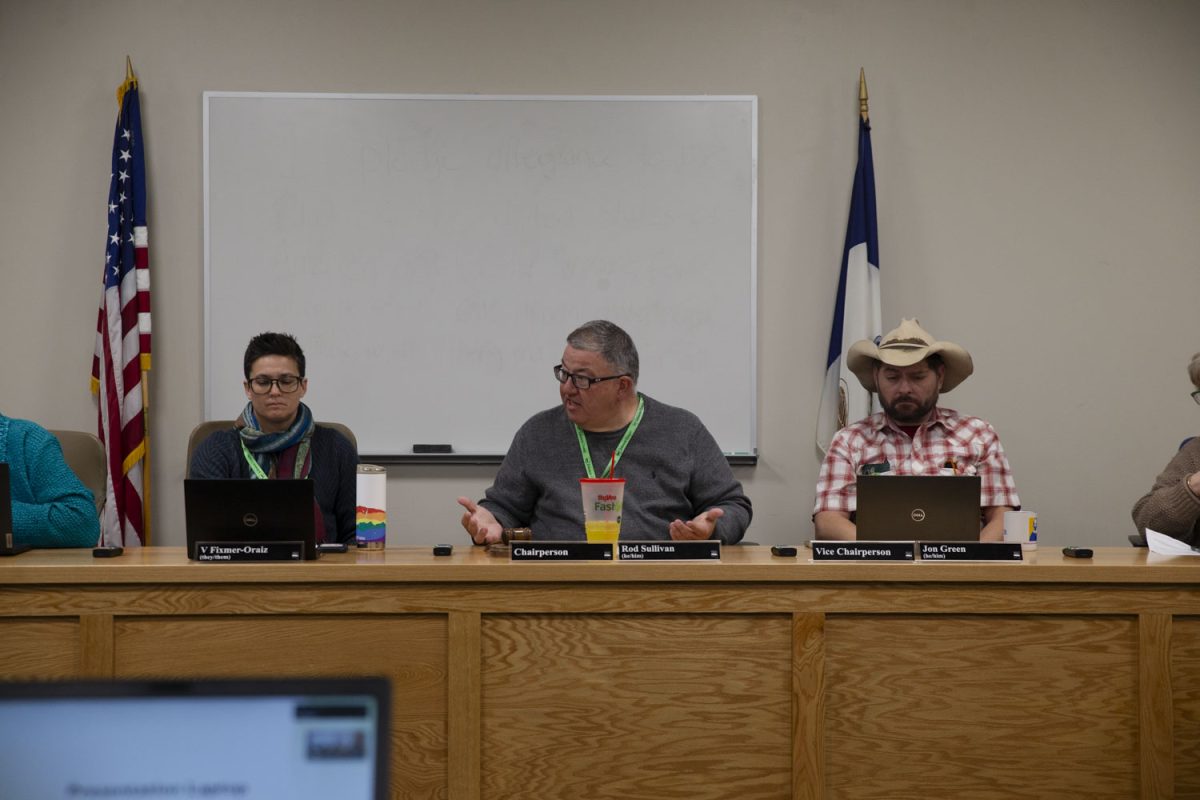

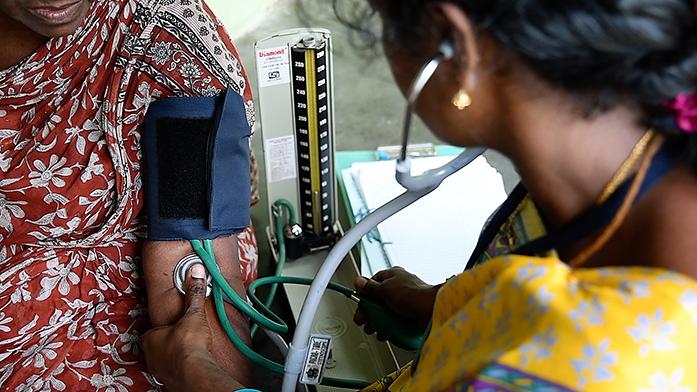

During my first trip to India, I spent my days shadowing the work of a palliative care organization in Pondicherry, our host-city, in the union territory of Puducherry. I accompanied nurses and doctors in cramped vans as they traveled to their patients, many elderly and impoverished, who lived in nearby villages. I captured photos and took notes on my iPhone, which I later posted on a blog. I posted one man’s story online with his photo. A number of my peers created activities for differently abled children, while others designed posters for a local eyecare hospital.

Each afternoon, I returned to the beachfront hotel where our group of nearly 30 Iowa students lived for three weeks. According to a 2008 Tourism Research and Marketing study, the latest I could find on this research, 1.6 million people worldwide travel as “voluntourists” every year, spending nearly $3,500 per trip on average.

Situated in a tourist neighborhood, we had access to Western-style toilets and a Pizza Hut just down the street. Still, evidence of India’s wealth gap appeared around the corner, where children begged camera-laden travelers for spare rupees. According to a 2016 World Economic Forum report, India has the second most unequal economy in the world. We stayed in Puducherry to celebrate Pongal, a four-day harvest festival, before flying home to a new semester.

* * * * * *

Describing his vacation on a social-impact cruise ship, New York Times author Lucas Peterson recounts teaching English to children in the Dominican Republic. “Did it make a difference with a capital D? Probably not,” he writes. “Would a trained teacher have done a better job? Undoubtedly.”

This outlines the principal concern experts in ethical tourism raise in opposition to global volunteer efforts: people performing tasks abroad they would be under-qualified for at home. According to a 2011 UNICEF report, high turnover of untrained international volunteers can result in children repeatedly learning low-level lessons, such as “singing ‘Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes’ every Monday.” Often, background checks are not conducted before volunteers begin work with children, which could pose dangers such as sexual and physical abuse.

And in medicine? Undergraduate students who stand zero chance of dispensing aspirin to patients at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics can easily find hands-on medical experience in poor countries.

In a 2016 op-ed piece for the Orlando Sentinel, Northwestern University Professor Noelle Sullivan writes, “A former student of mine volunteered in India as a high-school student, where he administered surgical anesthetics. During college, he went to Peru, where he administered shots, performed pre-natal checkups, tested patients for HIV and syphilis, and took blood samples.”

Approximately 70 percent of volunteer tourists are between ages 20 and 25, many of them still in college, according to the Tourism Research and Marketing study. Volunteer-tourism organizations have responded to this trend by partnering with universities to offer spring-break trips and academic credit.

Thompson)

The UI Study Abroad website warns students, “Although it often makes us feel good to volunteer, applicants must consider whether or not they have the skills and proper education to truly assist those they are hoping to help in an unfamiliar environment.”

Christine Brunner, a UI Global Health Studies instructor who leads three-day seminar on ethical tourism, challenges her students to ask themselves, “Can I do this at home?” when faced with any opportunity to “help” abroad. It’s a simple question often met with an even simpler answer: no.

For example, if a UIHC volunteer posted a patient photograph online, even on a private blog, detailing his ailment along with his name and address, he or she would be in violation of medical privacy rules. By Brunner’s logic, my doing so in India was unethical.

* * * * * *

Despite learning about the debate that surrounded “voluntourism,” I was eager to work with the palliative-care organization the following November, and it seemed equally as eager to welcome me back.

Its Facebook page and website needed updates. Its director wanted to make a YouTube video. Palliative-care awareness is a challenge both in India and the United States, where 70 percent of consumers rated themselves “not at all knowledgeable” about palliative care in a 2011 study by the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

Thompson)

Getting the word out is imperative to palliative care’s adoption worldwide, and as a journalism student, I felt confident that this was a task I could have surely embarked on at home. I agreed to help.

To hold a camera up to the face of another nation’s poverty invites further ethical scrutiny. India Winterim student Jordan Hansen said she thought a lot about what she posted on social media during her trip.

“I had to think about what perception of the culture my friends and family would have,” Hansen said.

One UI medical student who takes photos when working abroad, outlined to me three strict rules for capturing such images: one, always ask permission; two, don’t shoot anything you wouldn’t shoot at home; and three, ask yourself, “What is the purpose of this photo?”

He told me a story of a coworker who took a photo of a baby in an African NICU and uploaded it to Facebook and Instagram. “In the United States,” he said, “she would lose her job.”

I rode along with the palliative-care staff to villages in which patients would invite us into their homes for their checkups. Did the patients feel coerced into being on camera because their doctor asked, or even more troubling, because an American was holding the technology? Was I actually the one taking advantage of vulnerable individuals?

Thompson)

I countered these questions with the belief that captivating storytelling can change the way people perceive stigmatized topics such as poverty and terminal illness. Through my lens, I captured grass-roots activism, progressive feminism, and fierce compassion — all driven by leaders in the local community.

I learned to address the patients with affection, calling the older women “paati,” the regional word for grandmother, and the men “tata,” or grandfather. Still, I struggled to write translations and edit video interviews spoken in the foreign language. Catching the bus, following directions — everything proved difficult because I couldn’t latch onto the order woven into India’s chaos. One questionable samosa could take my stomach out for a week.

What then, should be said for “voluntourism”? When executed ethically, global travel can result in a social consciousness that could be achieved no other way.

Maybe instead of traveling abroad to “help,” students should travel abroad with the intention to learn — to learn about not only where they are stationed, but about where they are from.

“If Slumdog Millionaire projects India as Third World dirty underbelly developing nation … let it be known that a murky underbelly exists and thrives even in the most developed nations,” wrote Bollywood star Amitabh Bachchan following the film’s release.

If helping is indeed the guiding force, one might consider how the cost of a plane ticket and a few hours of volunteer work could bring light to a “murky” situation just down the street.

* * * * * *

We double check our pockets for keys, leave our bags in the sand, and run toward the waves. This stretch of the Indian Ocean is ours for the afternoon. Behind us, colorful fishing boats rest on the beach, awaiting tomorrow morning’s catch.

In the distance, we see a gang of young boys approaching our spot. They are maybe 8 or 9 years old, the sons of nearby fishermen. I exit the waves for my bag. It contains my iPhone and wallet, sure targets for theft, I think.

Instead, one boy approaches me and hands me a shell — a gift. Who am I to think they want what I’ve got?