By Maria Curi

maria-curi@uiowa.edu

In West Liberty, just 15 minutes east of Iowa City, pedestrians recognize each other across the street and wave hello to familiar faces.

In this small, rural town of about 4,000 people, on a regular day, it’s quiet. But on the day of West Liberty’s second Fiesta Latina, the deep strums of the Mariachi Guadalajara’s guitarrón player roared in the city center.

On this early fall day, locals driving their cars and pickup trucks were blocked off from a chunk of downtown’s East Third Street. The brick road was occupied by women who swung their long yellow, blue, and red ruffled skirts from side to side to the sizzle of the trumpet and the smoothness of the violin — iconic in folkloric Mexican music. Food stands lined the street offering anything from turkey filets, beer brats, and corn dogs to tacos, tostadas, and piñas locas.

The Fiesta Latina, sponsored by the League of United Latin American Citizens of Iowa (LULAC), an organization with a mission to mobilize Latinx voters, puts a spotlight on the day-to-day harmony between different cultures in West Liberty. This is a place converted by Latinx people into the first minority-majority town in the 91 percent white state of Iowa.

Rows of two-story buildings host small businesses owned by non-Latinx-Americans and Latinx-Americans in equal numbers; Fred’s Feed and Supply hardware store here, La Paz Market there.

This motley collection of locally owned businesses serves as a brick-and-mortar symbol of both a state and national trend in which the Latinx population and its eligible voters are growing among a dwindling white majority — and with that growth comes increasing political clout.

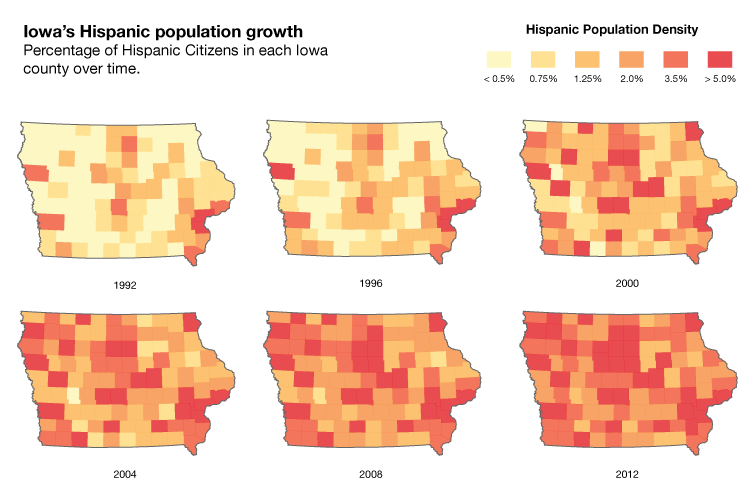

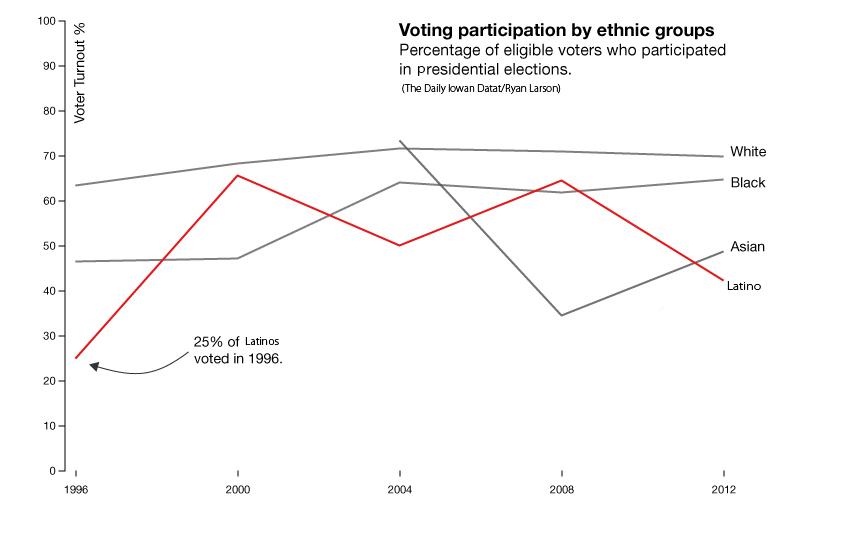

Pew Research Center data project that by 2065, the current 62 percent ethnic majority of white Americans will fall to 46 percent while Latinx people will come second at 24 percent. It also projects a record 27.3 million Latinx people across the United States will be eligible to cast ballots this Nov. 8. According to the State Data Center of Iowa, the current 5.7 percent Latinx population in Iowa will spike to 12.9 percent by 2050. Even though that population is growing in Iowa, research conducted by The Daily Iowan concluded that eligible voters in the Latinx population in Iowa are voting at significantly lower numbers than their Anglo-American counterparts.

![]()

Maria Bribriesco is the great-great-granddaughter of a Mexican man who was living in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in 1790 when the river changed and his town later became part of U.S. territory.

At the Fiesta Latina, the Bettendorf resident stood by a white LULAC van with the words “¡Su voz es su voto!” or “Your voice is your vote!” painted on the side in big blue letters. That day, matching the enthusiasm of the paint job, Bribriesco worked to mobilize Latinx voters as she has been doing all across the state.

“I’m trying to get the Latinos out to vote because I want this country to know that we’re growing in number, and we are going to be a force to be reckoned with,” Bribriesco said.

Although LULAC is a nonpartisan organization, and Bribriesco mobilizes the Latinx electorate regardless of party affiliation, in her opinion, a Donald Trump presidency would lead the nation down a road of discrimination and segregation.

“This election will determine what kind of people we are,” Bribriesco said. “This is where we make the stand. Are we going to take into consideration that we are Americans and we are from all types of nationalities and backgrounds, or are we going to start treating people differently because they are Latino or have a Spanish surname?”

Latinx voters have favored the Democratic Party over the Republican Party in every presidential election since at least the 1980s, according to the Pew Research Center.

A Democrat, Bribriesco sat down with Republican friend Johnathan Ortega to discuss the climate of the 2016 election and the importance of the Latinx vote.

In the early 1900s, Ortega’s father escaped the volatile aftermath of the Mexican Revolution and crossed the border into the United States, where he met the woman who became Ortega’s mother and planted roots.

Also from Bettendorf, Ortega works for the Republican Party of Iowa and mobilizes voters for a Trump presidency. For some Latinx people such as Ortega, religion-bred conservatism is better satisfied by the Republican agenda.

“I don’t believe marriage is between two men or two women. It’s between one man and one woman, as God created,” Ortega said. “That’s part of the problem; they [Democrats] are taking religion out of the government.”

Hints of friendly teasing were sprinkled into the sound of Ortega’s and Bribriesco’s voices as they defended their views.

“Why Donald Trump? Because he is not a politician,” Ortega said. “The politicians we’ve had in the past on both sides, Democrat and Republican, have been politicians … it’s for their own good, not for the good of us people, and I think Donald Trump is for all the citizens of the United States, including Mexicans.”

![]()

More importantly than how Latinx voters cast their ballots this election, relationships, Sal Alaniz stressed, are essential to fostering the inclusivity seen in West Liberty. Alaniz is the grandson of immigrants who came to the United States from La Piedad, Mexico, in the 1920s.

He was born in a Chicago neighborhood immersed in a plethora of cultures from African Americans to Greeks to Italians. This taught him at a young age the importance of encouraging harmonious communities.

Now, Sal is a small-business owner and resident of Mount Pleasant, Iowa, about an hour south of Iowa City. He is also the founder of the Center for Cultural Initiatives, an organization with a mission to promote relationships between the majority and minorities.

“We may have our differences in faith, gender, color of our skin, or tradition, but I do believe we are all one people,” Alaniz said. “For there to be less disparity and more welcoming communities, we need to be in relationship.”

![]()

According to the 2010 Census 5.3 percent of people in Iowa City are Latinx.

Noe Tellez, a restaurant manager in Iowa City, crossed the Mexican-United States border unauthorized when he was 19. He is now 37 years old and an authorized permanent resident.

According to Pew Research Center, there were 11.1 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States in 2014; 52 percent came from Mexico.

In the speech that launched his campaign, Republican presidential nominee Trump said, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

Sitting on the couch in his mobile home, in a humble and matter-of-fact fashion, Tellez recounted his journey across the Mexican-United States border. Every now and then, he glanced at his TV, where photographs of his daughter faded in and out of the screen. There were no other traces of family in his home.

In a low and steady voice, he said migrating was simply a matter of working hard for one’s dreams. No sounds of complaint or pain could be detected.

Tellez grew up in Venustiano, Carranza, a rural town in Mexico with little opportunity. His father was a campesino, working as a farmer.

At 17, Tellez left Carranza and went to Mexico City, where he found employment by pulling a dolly with one thousand pounds’ worth of plastic bags on it from store to store all around Mexico City, what is referred to in Mexico as the work of daibleros. After two and a half years he went from being a diablero to a salesman, but the poor quality of life in Mexico persisted and caused Tellez to make the decision to go to the U.S.

Tellez was pulled across the Rio Grande on an inflatable boat tied by rope around the waist of a swimming Mexican man. The tall grass alongside the U.S. shore of the river hid Tellez from border patrol for eight hours that July night. At 3 a.m., an unknown person in a pickup truck pulled up.

Tellez and 10 other men squeezed into the vehicle and were dropped off at el tiradero — the dump. There, the 28 hour walk across the Texas desert began.

“I just had it in my mind to get to the United States,” Tellez said. “I had it in my mind that I was going to work hard and finally see results and that kept me strong enough to keep walking.”

Hungry, thirsty, and dirty after five days of not showering, Tellez made it to the house of the coyote — who was in charge of overseeing the smuggling — in Houston. Ten days later, he was in Iowa, and finally his new life in the United States had begun.

![]()

For Cara Calvin McFerren, West Liberty’s first Latina councilwoman, immigrants and Latinx-Americans are a positive social and economic force in the United States.

The median age of Iowa’s Latinx population is 22 in comparison to the rest of the state’s age of 38, according to the State Data Center of Iowa. Young Latino immigrants propelled the once dying economies of towns such as West Liberty’s forward into prosperity.

As the great-granddaughter of immigrants who left Guanajuato, Mexico in 1908, and, following the construction of the Rock Island Railroad line, made their way to West Liberty, McFerren isn’t the first in her family to make history. Her grandfather graduated with West Liberty High’s class of 1933 and was the first Latinx person ever to receive a high-school diploma in the town.

A small-business owner, McFerren said the small and personal nature of West Liberty and its school system has allowed bonds to be built and differences to be bridged, especially among the children.

“The youth in this community that has grown up together, whether they are new immigrants or first-, second-, or third-generation minorities, all have one thing in common, and that’s the school system here,” McFerren said. “That’s really helped to close the gap.”

![]()

In the classrooms of West Liberty’s schools, the fusion of non-Latinx-American and Latino-American culture is striking. In the fall of 1998, West Liberty became the first school system in the state to implement a dual-language program. From pre-K through senior year of high school, students have the option to learn in English in the morning, switch to Spanish in the afternoon, and graduate as bilingual and bicultural young adults.

In Iowa City, University of Iowa initiatives taken by the Center for Diversity & Enrichment have created opportunities for multiculturalism, including programs such as scholarships designed for students of Latinx background. At the UI, 6.2 percent of the student body is Latinx.

Maideli Garcia is the daughter of Mexican immigrants and a fifth-grade teacher in West Liberty Elementary School who lives in Iowa City.

Her parents left Guanajuato, Mexico and crossed into the United States in the 1980s.

When teaching, Garcia said, she is guided by the mission to inspire her students in the same way she was inspired years ago and said the dual-language program is a valuable tool to have in that pursuit.

“It helps them become better learners, better thinkers,” Garcia said. “It opens doors for them and makes them more marketable in the global economy. It lets them have those relationships that they might not be able to have if they didn’t speak another language.”

![]()

Other city leaders around the state and the nation might look to West Liberty when modeling the demographic changes that will surely come in their own communities.

After the election, Latinx members of both Democrat and Republican parties will be affected by the policies the new leader of the free world implements — particularly concerning immigration.

“Iowa is a swing state and first in the caucuses. The eyes of the country are on us so this is a chance for Hispanic voters to have their voices heard,” Bribriesco said. “As Iowa goes, so goes the nation.”