In December 2023 in Cairo, Mazahir Salih saw suffering. There to find her mother who had just fled Sudan, Salih witnessed the lines of tired and hungry Sudanese refugees outside of the U.N. location in Sudan, all of them with the same hope — safety.

The Sudanese refugees Salih saw lined up before the U.N. office in Egypt had just escaped a deadly civil war and humanitarian crisis in Sudan, the devastation of which is not only felt in Africa but over 7,000 miles away in Iowa City as well. This war has also upended the lives of the Sudanese community in Iowa City, many of whom feel it is ignored in the U.S.

Given the emphasis on the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Hamas war, the Iowa City Sudanese community fears their nation has been lost in the noise.

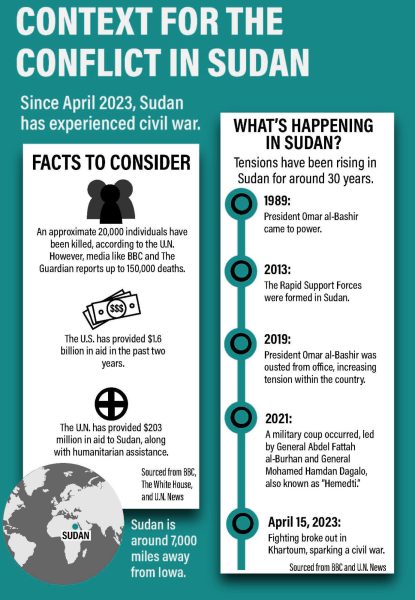

In April 2023, Sudan descended into civil war when its army, the Sudanese Armed Forces, and a paramilitary group, the Rapid Support Forces, began a fight for power over the nation.

The RSF and SAF initially worked together to execute a military coup in 2021, and then established a government co-led by the groups. However, over time their visions for Sudan began to diverge, and these tensions led to fighting breaking out in Khartoum.

The conflict in Sudan has been unmistakably violent, yet Dominique Hyde, the director of external relations at the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, the U.N.’s refugee agency, has criticized the global order for not giving the conflict in Sudan the attention it warrants, saying “the world is not paying attention” in a U.N. News article.

President-elect Donald Trump has not expressed a foreign policy plan regarding the Sudan civil war, though he often boasts of a domestic-focused “America First” foreign policy.

“The war comes to every house in Sudan”

Haitham Osman came with his family to Iowa City in 2018. Originally a physician in Sudan, Osman now serves as an

Americorps member at the Immigrant Welcome Network of Johnson County and has recently completed his master’s in public health at the University of Iowa.

In his office at the network, with rain tapping the window beside him, Osman recalled how his family was in Sudan when the war broke out in 2023. In the early stages of the war, the Rapid Support Forces came to their city, Jabal Awliya, so they fled.

Then, the Rapid Support Forces arrived in their new city. They moved again. The Rapid Support Forces came again.

Seemingly unable to escape the war domestically, Osman said his family had no option but to flee. They fled to Egypt, traveling sometimes in cars and other times on foot. This was particularly difficult for Osman’s mother, who is in her eighties and had a heart valve replacement.

Osman said the inevitability of the violence is a defining characteristic of the war in Sudan. He said the Rapid Support Forces comes to each village with the intent of killing its people, and sometimes the Sudanese Armed Forces will come to the villages in helicopters, shooting unsuspecting victims from above.

“The war comes to every house in Sudan,” Osman said.

Even those in Iowa City have been affected by this unrelenting violence. If not in Sudan themselves when the war began, many have families who remain there. The community bears the burden of not just trying to help their family escape Sudan but also the grief for their loved ones who couldn’t make it out soon enough.

Osman said every day he sees an announcement in the WhatsApp group that someone in Iowa City has lost a family member.

Salih, an Iowa City City Councilor believed to be the first Sudanese American to be elected to public office in the U.S., agrees the toll of the war has been significant on the Iowa City Sudanese community, and she echoed Osman’s sentiments that the killing is relentless.

“They’ve been killing everyone,” Salih said. “They go to any small village, and they just start killing people.”

Salih said she has lost one of her childhood friends, who was killed by the Rapid Support Forces after they intruded into her home. Salih’s friend resisted the Rapid Support Forces, and Salih said this act cost her friend her life.

“They just killed her in front of her children,” Salih said. “She died immediately. It [the bullet] went straight into her head.”

Salih’s two sisters, along with her mother and brother who are also both U.S. citizens, were all in her hometown — the nation’s capital city of Khartoum — when the war broke out.

They struggled to flee due to the inaccessibility of the U.S. embassy’s scheduled buses to Port Sudan. Salih said bus passengers were notified by email just hours before departure, even though the internet in most of Sudan had gone down.

The need to flee increased for Salih’s family, she said, when the Rapid Support Forces went into Salih’s family home and assaulted her sisters and their children. The Rapid Support Forces also stole everything of value in the home.

“My niece was wearing a necklace, they just pulled it from her neck,” Salih said.

Once targeted, the family knew they could no longer stay in Khartoum. They fled to Port Sudan, and on the way were stopped and searched by the Sudanese Armed Forces. Once at Port Sudan, Salih said the Sudanese Armed Forces accused Salih’s sister of being a part of the Rapid Support Forces, and they assaulted her.

Finally, Salih says she was able to fund her mother’s and sisters’ passage to Egypt — a trip during which many, including a friend of her sisters, died along the way from heat exhaustion.

Salih was able to travel to Egypt to collect her mother and was shocked by what she saw. She says those who had fled from the war in Sudan lined up outside of the U.N. office for hours, seeking refugee papers. They would wait overnight, Salih said, and then when they were finally seen, they would be scheduled for another appointment six months later.

Salih said those in Egypt, including her sister, are only able to rent the smallest and most crowded apartments in the lowest-rent districts, oftentimes with several families living in these crowded spaces at one time.

Beyond the loss of life, the war has caused a financial strain on the Iowa City Sudanese community.

Mohammed Aldirderi has lost some of his family to the war. Luckily, his immediate family is safe but requires financial assistance from him — which he doesn’t hesitate to provide. But, as a Kirkwood Community College student who is also supporting himself, Aldirderi said this has caused him to live from paycheck to paycheck.

Osman is experiencing a similar struggle. Now in Egypt, Osman’s family is not able to work. So, he supports them. This financial burden has been significant. Knowing his family depends on him, he pays all of their expenses, but it affects his budget and has an impact on his family in Iowa City. With a limited income, being the primary supporter of multiple families has been a strain.

Osman even gets requests for money from people who aren’t his family. In his Sudanese news Whatsapp group chat, Osman receives messages from members who notice he has a U.S. phone number and think he may be able to help them.

“Even today, I received a message from a guy who told me that his mother is very ill, and he needs my help,” Osman said. “He doesn’t know me.”

Iowa Sudanese community criticizes response

With loved ones lost, displaced, victimized by sexual violence, or unable to support themselves financially, many in the Iowa City Sudanese community are shocked by the lack of attention this conflict has garnered in the U.S.

After her family was targeted by the Rapid Support Forces, Salih was desperate to get them out of Sudan, so she contacted the governor, department of state, and even the president. Salih eventually got in contact with the U.S. Embassy in Sudan and was told there was a plane her mother could take to the U.S. She said her mother was unable to board the plane, and Salih struggled to get further help evacuating her mother from Sudan.

This experience was illuminating for Salih, and she continues to feel frustration with what she perceives as a relative lack of critical aid being provided to Sudan by both the U.S. and international governments.

Salih has since brought her mother to the U.S.

Salih isn’t optimistic about the future of this conflict. She said she did not see adequate attention given to the conflict under the Biden administration and doesn’t expect any better from the Trump administration. She fears that as the conflict progresses, more Sudanese will die, not just from violence but from the indirect effects of the war as well.

RELATED: Sudanese Americans protest ongoing military coup in Sudan

“If they have not died from the bullet, they will die because they’re hungry or because they don’t have medications,” Salih said.

Haida Elzabir, who was in Sudan when the war began, said she is devastated by what she perceives as a lack of an adequate response from the U.S. and other international powers regarding the war in Sudan.

Elzabir said the U.S. and its allies have enough money and influence to make a genuine impact on Sudan even regarding things that may be viewed as simple. One of these things is clean water, which she said Sudan lacks. To get just a sip of drinking water, Elzabir said she would first have to move the dust and debris out of the way.

Elzabir feels the U.S. media and politicians are ignoring the war in Sudan, instead focusing on the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Hamas war. She fears that nobody in the U.S. is seeing what’s happening in Sudan, from the poor living conditions to the significant loss of civilian life.

Given this lack of attention, Elzabir said this conflict and the lack of coverage it has received are both figuratively and literally erasing the identity of the Sudanese people.

Ayman Sharif, the director of the Center for Worker Justice of Eastern Iowa, said the political response and the media’s response are interconnected.

“Media is a response to politics,” Sharif said. “If politics is directing the media to respond, then the media will respond.”

Given the number of those killed, displaced, and raped, he finds it unusual that the media response has not been greater.

Sharif also finds a strange discrepancy in the fact that the U.S. has been a key player in the conflict since the beginning, getting involved in talks and forming avenues to resolve conflicts throughout Sudan, but ultimately it still isn’t getting media attention.

“It doesn’t make sense if the United States has all this interest and is putting in all this political effort at a high foreign policy level, whereas at the same time, nothing really is mentioned about this in the media, so nobody really notices, like this is actually what is happening,” Sharif said, referring to the U.S. special envoy to Sudan’s visit in November.

Ultimately, Sharif believes it is the choice of the international political world, consisting of global powers with invested interests in this war, not to end this war. He said these global powers tend to influence global conflicts and crises throughout the world generally.

Sharif said the conflict will not be resolved until the global political world feels satisfied with its outcome.

“The conflict will continue until the interest of the big players is achieved,” he said.

Iowa experts say U.S. interests contribute to media

Brian Lai, a UI political science professor and department chair, said the Sudan civil war has sparked divisions within the country that had previously been settled.

Lai said over time, the conflict has spread and gotten more intense. Lai said this is in part due to the Rapid Support Forces’ recognition of the writing on the wall. As the Rapid Support Forces face losing to the Sudanese Armed Forces, Lai said the army has begun to engage in more war crimes such as mass sexual violence. According to Lai, this comes down to their desire to control the populace and punish those who support the Sudanese Armed Forces.

Though the humanitarian crisis in Sudan is extreme, Lai said that, as opposed to the Ukraine and Gaza wars, it doesn’t present an immediate threat to U.S. interests. This is what contributes to the lack of attention the conflict has received from U.S. media.

Lai said the media has a finite amount of space to report, so they’ll report on issues regarding domestic politics, and then international issues like Gaza and Ukraine that are already taking precedence.

Much of this comes down to political involvement. Lai said when facing a humanitarian crisis like this one, the U.S. will involve itself with economic sanctions or promote negotiations among participating parties, but it won’t get directly involved.

According to Lai, this is in part a result of the U.S.’s failure to resolve the conflict in Somalia, where the U.S. has provided over $818 million in aid and U.S. troops have now been stationed for counterterrorism efforts since 2003, with no end in sight.

He thinks this failure has contributed to the U.S.’s unwillingness to involve itself in foreign humanitarian crises, particularly in Africa.

Lai said this lack of involvement not just in Sudan but in Africa as a whole contributes to a lack of media coverage of African conflicts generally.

In the future, Lai said he thinks the U.S. will continue its current approach toward Sudan or even be less involved as the Trump administration focuses foreign policy efforts toward things like tariffs on China.

The fighting, then, will continue, and the humanitarian disaster will continue as well.

“Unfortunately, if regional actors can’t find a way to get those two sides to commit to some kind of peace agreement, you’ll see just continued violence,” Lai said.

This prediction is not at all different from that of the Iowa City Sudanese community.

Salih said even with the recent presidential election, she doesn’t expect to see any change in the U.S.’s approach to Sudan.

She didn’t see the attention she expected from Biden’s administration and doubts that a Trump administration would make strides to intervene and end the conflict.

“I don’t have a lot of hope,” Salih said.