Editor’s note: This article contains mentions of sexual violence.

Starting as a hotline for women in crisis over 50 years ago and evolving into a leading program for sexual assault victims in Iowa, the Rape Victim Advocacy Program — also known as RVAP — at the University of Iowa is now facing its final days of operation.

Five months ago, the UI announced it would transition all RVAP’s services by Sept. 30 to the Iowa City community nonprofit Domestic Violence Intervention Program, also known as DVIP, and layoffs would follow.

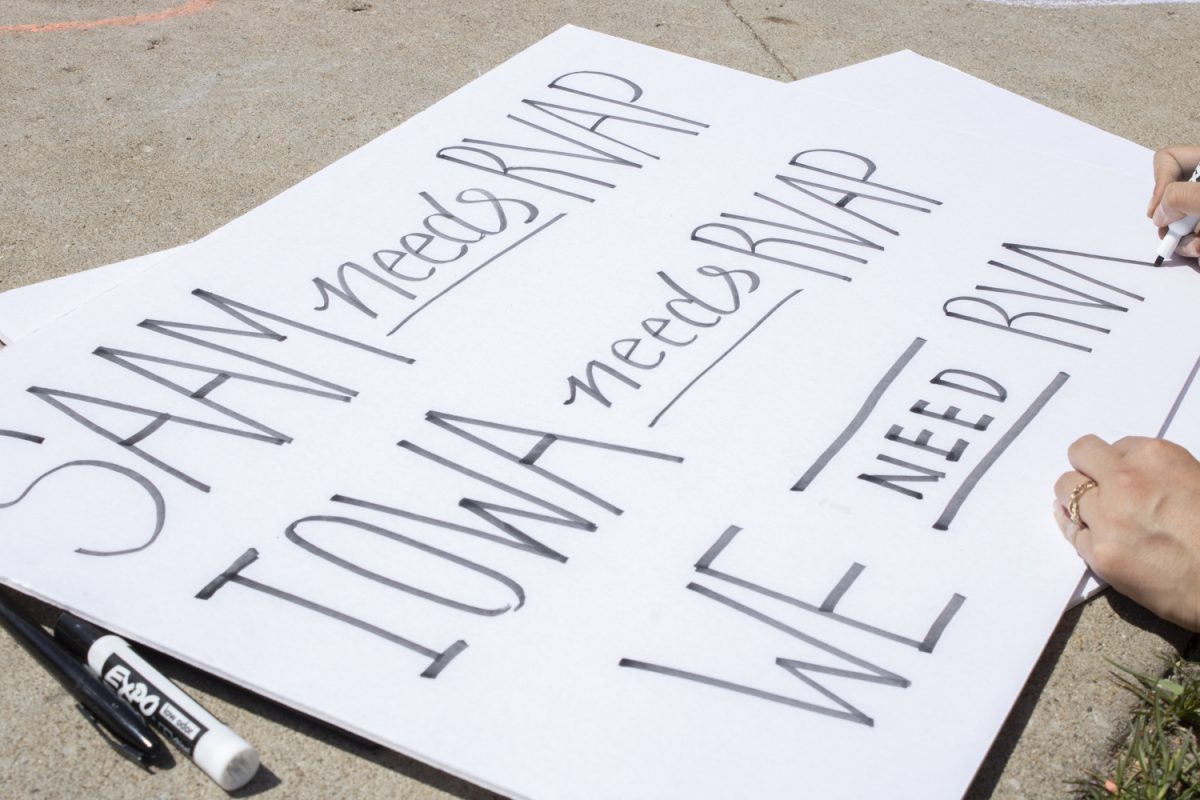

The news stunned students, resulting in protests across campus over the following weeks. Those who were most surprised, though, were RVAP’s own employees.

Staff told The Daily Iowan in April that many of them learned of their impending dismissals through news outlets and a campuswide email informing the public of the changes.

In its announcement, the university cited RVAP’s low rate of helping survivors on the UI’s campus. The vast majority of their clientele, according to the UI, came from outside the university community, in the eight counties — including Johnson — that RVAP serves.

The university argued that for RVAP to expand and thrive, it would be best for the organization to leave the university.

The decision left a glaring question: How, in five months, was DVIP supposed to take on the multitude of services offered by RVAP?

Ultimately, a combination of ensuring funding and establishing DVIP as a resource for sexual assault survivors would become their biggest hurdles.

DVIP is now taking those head on. The organization is recruiting staff and finalizing agreements with the UI this week. Now, with the transfer just days away, DVIP is set to continue a legacy that has been in the making for over 50 years.

Sister organizations

Both RVAP and DVIP originated from the same organization: the Women’s Resource and Action Center, or WRAC. WRAC was launched in 1971 during a time when the women’s rights movement was taking the country by storm throughout the decade.

Today, WRAC — housed at 230 North Clinton Street — works to provide equitable opportunities in the community, provide educational resources to fight social injustice, and encourage advocacy.

In 1973, a group of WRAC volunteers created Women Against Rape and started a rape crisis phone line. They staffed this phone line every day and every night, an effort that grew into RVAP. By 1998 RVAP expanded its services to several counties, becoming an invaluable resource for sexual assault survivors in rural Iowa.

In 1979, DVIP was formed, two years after WRAC had received a grant to address domestic violence in the community. By 1980, DVIP had opened its own shelter for domestic violence survivors and started its 24-hour crisis line.

In the 2000s, RVAP was organized under the UI’s Division of Student Life where it remained until 2024. RVAP was not just a phone line. The group developed direct advocacy services, became a confidential therapy resource, offering support groups, and more.

Side by side, both organizations grew. DVIP came to serve the same eight counties as RVAP. In 2013 the state of Iowa reorganized sexual assault and domestic violence services into six regions.

DVIP and RVAP were grouped into Region Six. Most of the other regions had their sexual assault and domestic violence services combined, which left Region Six as an outlier.

While RVAP and DVIP offer similar services, DVIP is not housed by the UI. However, it was the shared service area that factored into the university’s decision to transition all RVAP’s services to DVIP.

Why did the UI decide to cut RVAP?

Vice President for Student Life Sarah Hansen said the transition of resources from RVAP to DVIP would enable RVAP to grow its services. In a press release sent out in April, the university cited that about 12 percent of direct services and only 7 percent of crisis calls were used by or from UI-affiliated individuals.

DVIP has 33 staff members that cover its service area, while RVAP had just 12, with an additional seven who worked the phones overnight. Chris Brewer, the UI public relations manager, said in April that six of RVAP’s staff would be laid off by the closure, two had been previously notified of layoffs, and four of the employees’ contracts expired on June 30.

Hansen told the DI in April that RVAP’s role at the university was something they had been discussing for nearly 25 years.

Even Hansen admitted that the communication to RVAP’s staff was rushed. She said that information about the transition was spreading, and it led the UI to move quickly.

“We had some folks who communicated — I think inappropriately — about what was going to happen, and we were really worried about the staff hearing from people other than us,” Hansen said in April.

In an email from May obtained by the DI, former volunteer coordinator Storm O’Brink wrote to RVAP’s staff that the reason the university cut RVAP ran much deeper than low service to UI staff and allowing RVAP to expand.

In the email, O’Brink said the university did a program review of RVAP in 2022 and the findings suggested multiple services should get cut. These included doula services, youth therapy, and queer health advocacy.

O’Brink also wrote that the staff at RVAP pushed back against these requests, which they claimed caused conflict within the university.

Former Interim Director of RVAP Diane Funk had served various roles within RVAP for over 20 years, but had left for some time before returning as the interim director in September 2023. O’Brink wrote in the email that Funk was sent to make RVAP fall in line with the initiatives set by the 2022 program review.

Hansen confirmed in a recent interview with the DI that implementing the 2022 program objectives was part of Funk’s goals. Hansen also said that part of the reason they recommend those services be cut is because RVAP was beginning to struggle to meet standards set by the Iowa Colation Agaistn Sexual Assault, known as IowaCASA, by overextending their work.

O’Brink claimed it was ultimately Funk who recommended the UI cut RVAP and transition the services to DVIP. An investigation from Iowa Public Radio found RVAP’s interim director had recommended to an UI administrator that they stop housing the organization in February.

O’Brink left their position with RVAP in May.

In an interview with the DI in April, Funk said that RVAP had always tried to serve both the community and the university, and the transition helps achieve that.

“I know that historically we had always tried to not be absorbed into the body as much because we felt like perceptions as a community organization, or the reality frankly being a community organization, allowed for us to serve the community and the university,” Funk said.

How is the transition going?

Several concerns perforated the community about the transition, including whether DVIP had enough resources, how survivors would find their services, and whether DVIP was an established enough resource known throughout the area.

So far, DVIP has held several initiatives to overcome these challenges — but it is coming down to the wire. With only the remainder of September until they are expected to take on all services, there is still no formal agreement between DVIP and the university for them to take over.

However, Hansen and DVIP’s Director of Community Engagement Alta Medea said that a written agreement between the university and DVIP was being finalized this week.

Over June and July, DVIP assembled a Sexual Assault Victim Services Advisory Council which met to discuss what services they wanted to continue into DVIP, Medea said. They also created working groups in each of the eight counties to work with individuals through the transition.

In April, DVIP’s director said they would hire 10-15 new staff members to take over the services. In a recent interview with the DI, DVIP’s Medea said they have hired nine out of 10 open positions as of Sept. 12.

Two advocates will be housed at WRAC, Medea and WRAC’s Director Linda Kroon said. The university is also adding another educational staff member to WRAC, Hansen said.

Hansen also said the university would be committing around $125,000 to DVIP for the advocates at WRAC.

Medea said no employees from RVAP applied for positions at DVIP.

To provide a seamless transition, Medea said they have rebranded DVIP to include RVAP’s name, and they are continuing the same crisis line for 18-24 months. On Aug. 21, they sent an open letter to RVAP’s clients to help them with the transition.

They also hired a new director for the sexual assault services, Shell Feijo, on July 17. Feijo has worked with sexual assault survivors and the university in the past.

“She has a wide range of experience both on college campuses as well as working directly with victim survivors,” Medea said. “We are extremely excited to have her in this position, and [it] has been incredibly helpful to have her expertise while we’re writing some of these grants to fund sexual assault services.”

Additionally, Medea said they are working to begin dual training for their advocates so that as they work with survivors of sexual assault, they will have full support. She also said they are testing the phone lines this week to make sure there is a seamless transition for the crisis line.

As of Sept. 16, RVAP’s website says that due to the upcoming transition, all their current services have decreased. However, Hansen said they have hired more than 30 temporary staff to ensure the hotline is always operational.

Funding

Brewer told the DI in April that RVAP operated off a $1.1 million budget, and they said they were committing their funding to DVIP. However, the university only funds 20 percent of that amount.

Most of RVAP’s budget came from grants allocated through the Office of the Attorney General of Iowa alongside grants and state funding.

Nearly $700 million is being cut this year in funding to the Victims of Crime Act, or VOCA, which funds victim crime services across the country. Medea said that victim services are feeling that cut this year but is hopeful that there will be more money available in the future.

At the end of July, Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds announced that Iowa would use $5.5 million from the American Rescue Plan Act this year for “one time bridge funding” of victim services.

For DVIP, this meant they would have the funding they needed to transition RVAP and finish initiatives such as a new emergency shelter, which increases the number of beds they offer by 30.

Medea said DVIP would serve both survivors of domestic violence and sexual violence. DVIP also has two transition shelters that are used to get people back on their feet. However, supplemental ARPA funding is not guaranteed past this year, and no one is entirely sure how much funding they will get next year.

Medea said they will continue fundraising to help meet their needs.

University sees backlash

When the UI first announced RVAP was closing, over 80 people gathered at the UI Pentacrest to protest the university for its decision. A couple weeks later, students again protested by demonstrating a sit-in outside Hansen’s office.

On April 26, the UI Council on the Status of Women, which works to build environments that support women’s rights, wrote an open letter to Hansen that criticized the decision to close RVAP.

“We are concerned about the lack of transparency in the decision to dissolve the Rape Victim Advocacy Program at The University of Iowa,” the letter read. “This lack of transparency and learning about the decision from a campus-wide email undoubtedly negatively affected RVAP clients and our students going through a Title IX or criminal investigation.”

The group also expressed concerns about what access would look like for students following the transition.

Olivia Brown works as a student on-call direct service advocate at RVAP and helped organize the protests in the spring. In a recent interview with the DI, Brown said they still believe the university is making the wrong decision by moving the program.

“I am still of the belief that you need to have two separate funding services for sexual assault and domestic violence,” Brown said. “They need two very different resource amounts, and they need different resources.”

Gail Osborn, a sexual assault survivor from rural Washington County, said in a recent interview that advocates from RVAP helped her at a critical point in her life. She said DVIP has big shoes to fill to reach the level of trust RVAP had in the community.

“I believe that DVIP has a fair shot of doing great things, good things for the people that need it,” Osborn said.

She said it will be important for DVIP’s staff to develop the community’s trust after the transition happens.

Sofia Day, a third-year student at the UI, said she first contacted RVAP when she was a freshman. She said that she was raped while on campus and RVAP’s advocates were people she could turn to in that moment.

She said advocates from RVAP helped her through that period, and she said even if there are still advocates on campus, it will not be the same.

“I think there are a lot of victims who need to tell their stories, and also a lot of them who are not ready to tell their stories,” Day said. “I think only having two [sexual assault advocates] on campus that they can go to limits how fast they can heal.”

Hansen said she thinks the campus will see the same level of attention from staff compared to RVAP. She said the two advocates serve as experts in a college campus setting.

What’s next

Looking forward, Medea said RVAP’s crisis line is being maintained, staff is being hired, and programs are being continued.

Whether these promises will be fulfilled in the future is yet to be seen. Medea said they are confident they will continue serving the university and the eight counties RVAP served.

Hansen said the university plans to continue working on its anti-violence plan, training staff, and seeking out new innovations. She said the UI also recently joined a study conducted by the University of Washington that is working on an application that helps survivors of sexual violence.

RELATED: University of Iowa officials on the ‘difficult step’ of RVAP transition

“We’ll continue to work on our anti-violence plan, which is a cross institutional plan that looks at intervention as well as the prevention components of this,” Hansen said. “So things like adding staff, making sure that our students are getting trained, that faculty and staff are getting trained on what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior across the whole range of things, from sexual harassment, to sexual assault, to stalking, to dating violence.”

While the UI has reported decreases in sex-related crimes on campus, this first few months of the fall semester has the most demand for sexual assault advocates, WRAC’s Director Kroon said.

Kroon said this time period is called “the red zone,” and she said staff are keeping up so far.

According to the UI’s crime report from 2022-23, 13 rapes were reported on campus in 2022. This number is down from 54 in 2021.

Reports of fondling were also down from 27 to 18.

According to the UI’s most recent Speak Out Iowa Survey from 2021, 16.6 of female students, 5.1 percent of male students, and 22.6 percent of transgender or gender non-conforming students have experienced a rape or an attempted rape in their life.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported over half of women and one third of men have experienced sexual violence in the U.S.

Medea said DVIP plans to build trust in the community through hard work.

“I think that trust is built through work, right? Like any type of relationship, trust is built on the way that you show up, and we have shown up for 45 years,” Medea said. “For victim survivors of intimate partner violence, I think continually centering victims to voices and decision making helps lead to that trust building.”